From the Archive: The Moon Dreamers

With the goal of telling the story of molecular biology firsthand, EMBL’s Archive is on the hunt for unique material significant to the Laboratory’s history: our new regular feature explores some of the highlights

By Anne-Flore Laloë

This edition we highlight an original artwork donated to the EMBL Archive by illustrator Edmond Baudoin (pictured). Last year, together with mathematician Cédric Villani, Baudoin published a book that explores the intense personal story of Leó Szilárd, a nuclear physicist who in part initiated the idea of EMBL. Les Rêveurs lunaires – or The Moon Dreamers – highlights socio-ethical issues intertwined with fundamental breakthroughs, also zooming in on the lives of code-breaker Alan Turing, quantum pioneer Werner Heisenberg and military commander Hugh Dowding. I caught up with Baudoin to find out more.

This edition we highlight an original artwork donated to the EMBL Archive by illustrator Edmond Baudoin (pictured). Last year, together with mathematician Cédric Villani, Baudoin published a book that explores the intense personal story of Leó Szilárd, a nuclear physicist who in part initiated the idea of EMBL. Les Rêveurs lunaires – or The Moon Dreamers – highlights socio-ethical issues intertwined with fundamental breakthroughs, also zooming in on the lives of code-breaker Alan Turing, quantum pioneer Werner Heisenberg and military commander Hugh Dowding. I caught up with Baudoin to find out more.

What did the book set out to achieve?

While we might know about the discoveries our main characters are famous for, we might not often think about scientists’ human journeys. The four protagonists made significant contributions to modern science, but also had to confront significant moral and ethical questions. How did they feel about their contributions to knowledge when they looked back on their work? Were they proud, ashamed, or confused? Our book aims to illustrate – and even challenge – the role of science in our society through their experiences.

It was important to reflect this complexity and layered depth in how I represented him.

How did you draw each character?

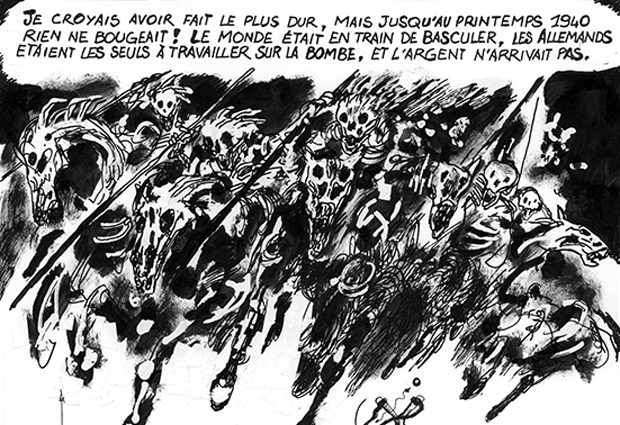

I adapted my drawing style depending on how easily I came to understand the individual. For Szilárd, as I learned about him, the different layers of his character and the complexities of his story meant that I wanted to use a special tool that scratched the surface of the paper – much like digging into his personality. During his life, Szilárd seemingly carries the weight of the world on his shoulders, together with the fear and personal tragedy that came part and parcel with being a Hungarian Jew in the first half of the twentieth century. I felt it was important to reflect this complexity and layered depth in how I represented him.

Describe your dynamic with Villani…

I was never really good at maths in school, so it was really magical for me to be approached by Villani, who liked my drawing style. The chemistry that developed between us was tremendous, and after reading his storylines over and over, the pages just flowed out – it felt like musical improvisation! But there was a lot of back-and-forth exchange. In one night scene, I had sketched a crescent moon and emailed the draft to Villani: he wrote back instantly explaining that on the evening of the scene – 6 August 1945 –, the moon would have been waning, not waxing and I redrew the page accordingly. It was a delight to work with someone with such meticulous attention to detail. For Villani, communicating science is a passion – almost an act of activism! Ultimately we both wanted to take advantage of the very popular medium of comic books to tell a narrative that could promote understanding of the role of science in a better world.

In English

“I thought the hardest was behind me, but until the spring of 1940, nothing was happening. The world was being toppled, the Germans were the only ones working on the bomb, and money was not forthcoming.

“And Fermi was in no rush to work on the project! Fermi, he was a pure scientist, his country’s best, but incapable of taking the political matters of the world seriously. He was always floating above us, working for the next millennium, and he didn’t give a damn about the bomb! He said our experiment was 90% likely to fail! Oh, but if we have a 10% chance of seeing the apocalypse, it’s worth a try, no? That was how I understood caution.”