Arrivederci Phil!

As he enters retirement, Head of EMBL Rome Phil Avner reflects on his scientific career and memories from his time as Head of EMBL’s site in Italy

The farewell party had been planned for months. It was meant to be in June, when the mild weather and the scent of the flowers would provide the perfect setting for enjoying some good Italian food and homemade beer in the beautiful courtyard at EMBL Rome.

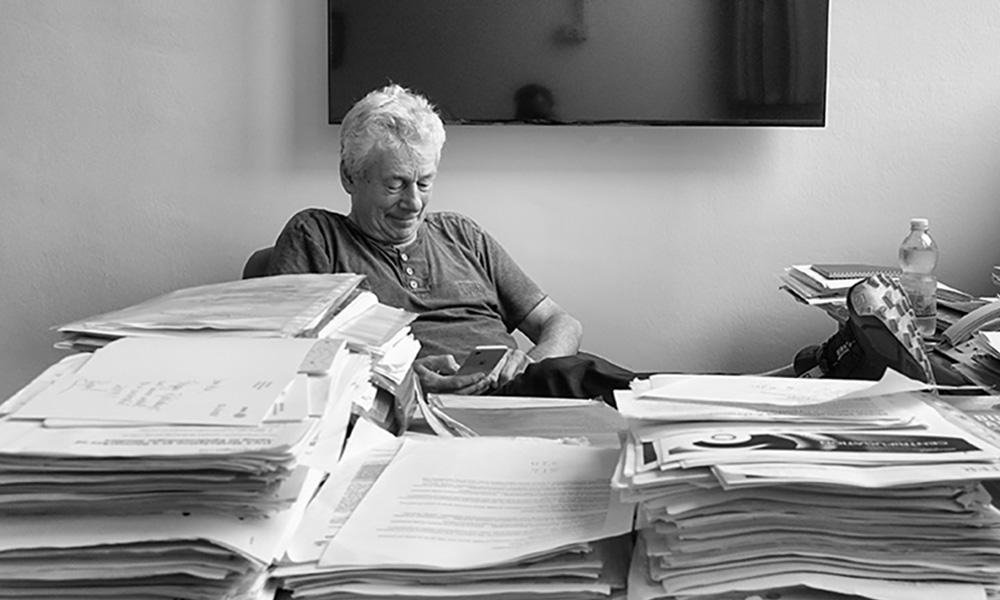

It was being arranged in honour of Phil Avner, retiring after a long career in science and eight years as Head of EMBL Rome. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, however, everything had to be rethought. It took some creativity to organise a proper farewell party via Zoom, but the fancy background set up by Phil’s personal assistant Helen Barker – and the affection of the people who attended, including EMBL staff and alumni – succeeded in making it a memorable and emotional event.

Phil is now at his home in the French countryside, relaxed and away from the big cities where he has lived most of his life. Here, Phil reflects on a career at the forefront of developmental biology and epigenetics, marked by changes both in the places he has worked and the scientific questions he has explored.

What impressed you most when you first visited EMBL Rome?

The first time I came to Monterotondo, I was part of an EU evaluation panel. I was impressed by the science and the atmosphere of the place – which seemed very happy. When I came back for my recruitment interview, I was again struck by the openness of the people, their competence, and the amazing welcome that I got from the administrative officers. EMBL Rome has been lucky and chosen its admin officers well. They, along with the scientists, have created something that is quite unique.

What convinced you to accept the role as head of the site?

Several things. Firstly, the competence and openness of the people I met. Secondly, the novelty – I was moving from the Institut Pasteur in France, where I was head of a unit and of the Department of Development, and I was very interested in experiencing the ways of another Institute. Thirdly, the idea of moving to Rome was very interesting, culturally and in many other ways. I think it was the package of everything, but especially the idea that I was moving into another structure with EMBL as the motor, with such a great reputation, and at the same time aware that there were huge differences in size between different sites, between Monterotondo and Heidelberg.

What have been your main challenges and achievements at EMBL Rome?

When I arrived, my initial preoccupation was to make sure that we more clearly focused our scientific interests, and raised our profile to be considered a fully worthy partner first of all by the rest of EMBL. Over time, as we made recruitments, we have exclusively focused on epigenetics and neurobiology. We then moved towards defining a core of potential partner laboratories interested in what we were doing. This work is very much ongoing, supported by the ‘EMBL in Italy’ alumni events, with the aim of building confidence with other partners and a platform for interactions over the long term. A major thrust of the ‘EMBL in Italy’ events has been to move the meetings out of purely academic settings to other settings including biotech companies. Some of our people subsequently have received job offers at these companies because their qualities were recognised, they met people and started to build networks, and that’s exactly what we need to encourage, so that our students have the opportunity to continue their careers in varied settings in Italy if they wish to.

What will you miss most?

The people. There’s no doubt. An amazingly warm community. There’s so much willingness at EMBL Rome to make things work, and you don’t get that everywhere. At EMBL Rome, with 99% of the recruitment we‘ve done, we’ve managed to recruit people who are competent, willing, and good community members, and that’s amazing. I don’t know how much of that is EMBL, how much of that is Monterotondo or Rome, or how much of that is Italy, but I feel blessed by the people I’ve worked with over the last few years.

Overall I think this is a super interesting and stimulating time for everyone working at EMBL, with the new lines of research that EMBL is developing and promoting, and a new Director General. I know her very well: she was my first postdoctoral student at the Institut Pasteur, and a fantastic scientist.

Tell us more about your career.

I grew up in the suburbs of London. I started studying to be a farmer at an agricultural science university, but then realised that not having grown up on a farm and not having parents who had a lot of money would make things very difficult. So I moved into plant science, and did a master’s degree followed by a PhD in yeast genetics.

In my career, I’ve always moved and tried to stretch myself with new ideas. I was also very keen on living in Europe. In 1972 I moved to the French national centre for scientific research (CNRS) in Gif-sur-Yvette as a postdoc in the lab of geneticist Piotr Słonimski, a Polish expatriate and a super scientist. It was an amazing time, just after 1968 – I was moving from an English laboratory where we talked about football, football, football, to a French laboratory where almost all they were talking about was politics. This cultural ferment and stimulating environment didn’t just remain linked to politics, but spread across the work we were doing. I learnt of a different way of running a lab, where you have to listen to everyone, rather than having a top-down perspective. That, in itself, was very interesting.

Then I decided to change projects again. The lab and I had good publications and Słonimski was an extraordinary person and yeast geneticist, but I had the impression that things were going so well that I could well spend my entire life in front of Petri dishes and yeast, and I wanted to change. I followed the advice of another distinguished scientist – Boris Ephrussi – and I ended up working with François Jacob at the Institut Pasteur, who, at the time, was part of a generation of scientists all working on bacterial systems, who were moving into the field of developmental biology. It was the start of a new field: we didn’t have very much molecular biology, we didn’t have very good cell biology, but everything was moving very rapidly. That was my second and last postdoc position. After that, I knew I wanted to work on mammalian developmental biology, but I also knew that I needed a system that could be modelled both in vivo and ex vivo and, if possible, one that displayed binary decision making. Through both luck and judgement, I hit upon the idea that X-inactivation in female embryos was potentially such a system, with new findings suggesting it could be modellised ex vivo. My work on X-inactivation started at the Institut Pasteur and was carried on a little bit in Rome. However, we tried not to stay completely wedded to a single system and started working on human genetics using mouse models. We made some big contributions to the mapping of mouse genes at a time when sequencing was not around. We were interested in applying such data to diseases, and got involved with excellent clinicians to work on type 1 diabetes in the mouse.

I’ve based my career on a degree of change and flexibility. Each time you change, it’s very stimulating. You lose expertise, and you lose some of your contacts – you have to be prepared for that. But it keeps you awake and you meet a lot of very interesting people.

What does the future hold for you?

I’ve retained my passion for plants and gardening, even though most of my career has involved living in apartments in big cities. The idea of having some time to go back and look at the seasons is of interest to me. At the same time, Paris has many cultural and artistic events that I would like to follow, which complement the ones we have enjoyed in Rome, such as concerts and the opera. Hopefully this will occupy me if I start feeling low because I’m not in Rome.