EMBL, Pliny the Elder, and a thematic approach to biological research

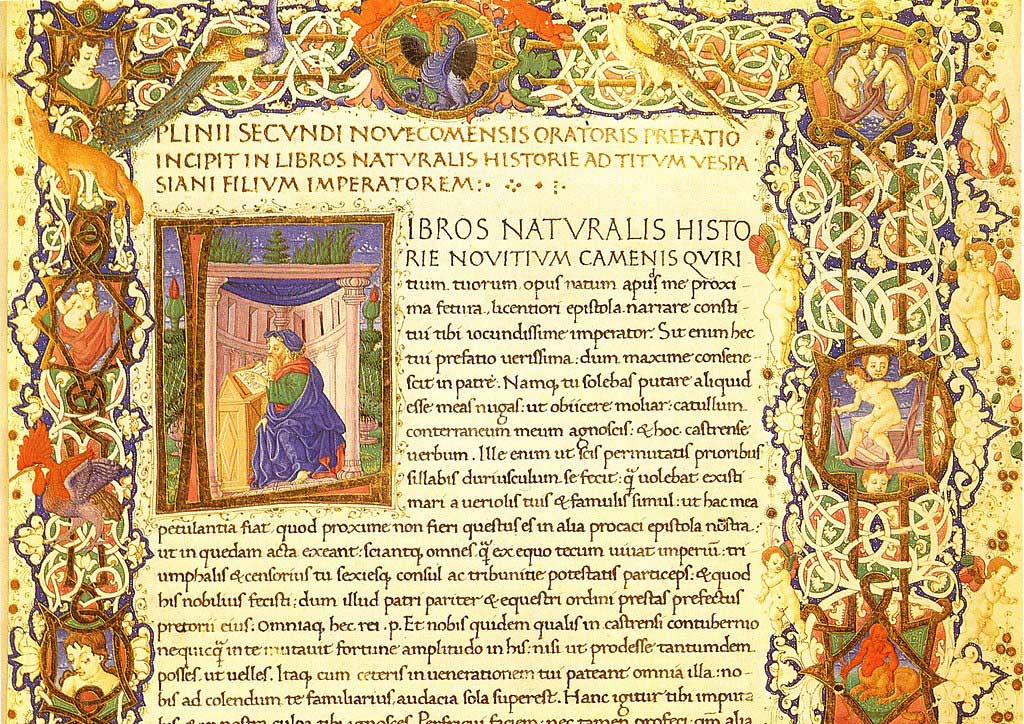

In his Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century AD, attempted to bring together all notable observations from learned people about the natural world. Travelling what was then the Roman Empire under Vespasian, he made observations, interrogated witnesses of natural phenomena, and read widely the notes and letters of correspondents. His aim was for his encyclopaedia to collect all the useful knowledge in the ancient world. Before his death in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, Pliny could conceivably claim to have collected all scientific knowledge then in existence.

A reader of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica could, in 1687, know everything there was to know about classical mechanics. In a similar vein, everything known about particulate gene transfer was once contained in a single paper published in 1866 in an obscure plant journal, written by Austrian monk Gregor Mendel. A studious reader could at various points in history have consumed all the available material on chemistry, physics, or biology.

How times have changed. Today, we have improved tools and techniques, instantaneous global communication, and a proliferation of topics and sub-topics. It is now quite impossible to have read “all” of science. Automated high-throughput data techniques and easy digital publishing have given scientists more data than they know what to do with. Drawing meaningful scientific conclusions from this wealth of data requires skilled analysts, time, and – increasingly – cross-topic collaboration. Scientists are crossing borders, both physical and intellectual, seeking fruitful collaboration with specialists from seemingly unrelated fields. Bioinformatics is a case in point – to wrangle useful knowledge from huge datasets, computer science skills are as in demand as biological know-how.

Research at EMBL is no exception. Though for administrative purposes we identify nine research units within neat categories such as Genome Biology or Developmental Biology, we understand that biological reality is messier. Topics of interest frequently overlap and scientists from different EMBL research units collaborate on cross-cutting projects.

To reflect this reality on our website, EMBL has established a series of functional structures called transversal themes. Five of these – Planetary Biology, Human Ecosystems, Infection Biology and Microbial Ecosystems – now have their own website. Each website is a hub for news, publications, events, and discussion about that theme. You can read more about EMBL’s approach to that area of multidisciplinary research and find out who to contact for more information.

I hope our transversal themes approach reminds users that not all scientific knowledge fits neatly into categories. Pliny published Naturalis in 37 books, organised into 10 volumes on topics from astronomy to zoology. Browsing the work online today, it is fitting that the publication is enriched with metadata, a search field, and cross references, to help readers to find common ground across diverse topics.