What is Core Content?

Whenever I introduce myself as EMBL’s Core Content Manager, I inevitably have to explain what core content is. The short answer is that it’s long-lasting content, that we can use in many ways, including to support the more news-y stories we tell. But what does that mean, exactly?

How long should core content last?

Let’s start with the ‘long-lasting’. How long is long? In my mind, I’ve been aiming for five years. This is an arbitrary number, but seems like a good place to start for EMBL. EMBL runs on 5-year programmes, and most people are limited to a maximum of 9 years working here. With this constant turnover, a lot can change in a short period. Creating a piece of content now and expecting it to still be usable and relevant in 10 years’ time – when virtually everyone it relates to has left, and at least one new programme has been implemented – smacks of wishful thinking. Over five years, there’s enough stability – even at EMBL – for a well-crafted piece of content to retain its usefulness. Of course, this will vary from topic to topic – and not always in predictable ways. An explainer of EMBL’s 5-year programme and associated budget will probably still be valid in 10 or even 15 years’ time – unless the process is changed, in which case the text will become instantly obsolete.

General principles that support multiple stories

Core content’s long life shouldn’t be a life of isolation. The idea is that this content – also called evergreen content – should be foundational material. It should clarify, provide context, or otherwise support future stories.

So core content deals in general principles. Specific discoveries can serve as excellent examples to illustrate a broader rule or show how we built up our understanding of a concept over time. But the more a piece focuses on them, the less re-usable it will be, and the fewer stories it can support. Take this article on Hiroki Asari’s work on vision. It touches on some general principles, like the concept of the retina as processor, not just film. And it explains techniques like calcium imaging. But it’s so centred on Asari’s interests and work that it’s hard to see the text being used as supporting material for any stories that don’t involve the Asari lab. This text on how Theodore Alexandrov uses maths to map molecules is slightly broader. Even though it wasn’t envisioned as a supporting piece, it could conceivably be used to provide context for a news story on metabolomics or to illustrate how mathematicians can help tackle biological questions. This story in Quanta about the geometry of viruses paints an even broader picture. I could see this supporting a report on a new discovery of how a particular virus assembles, or a piece on the history of the study of viruses, or on geometry and its applications, or on how mathematicians can work in biology, … or even on synthetic biology or new types of vaccines.

So a feature article can act as core content that other stories can link to or sit alongside. Shorter explainer texts or definitions can make useful ‘boxes’ to drop in every time you talk about a topic. For instance, this explainer on tissue biology gave some useful background information when EMBL announced a new site dedicated to that field. And as the scientists move into the new site and we start talking about their work, we’ll be able to provide that context again and again.

Repurposable content tells more stories

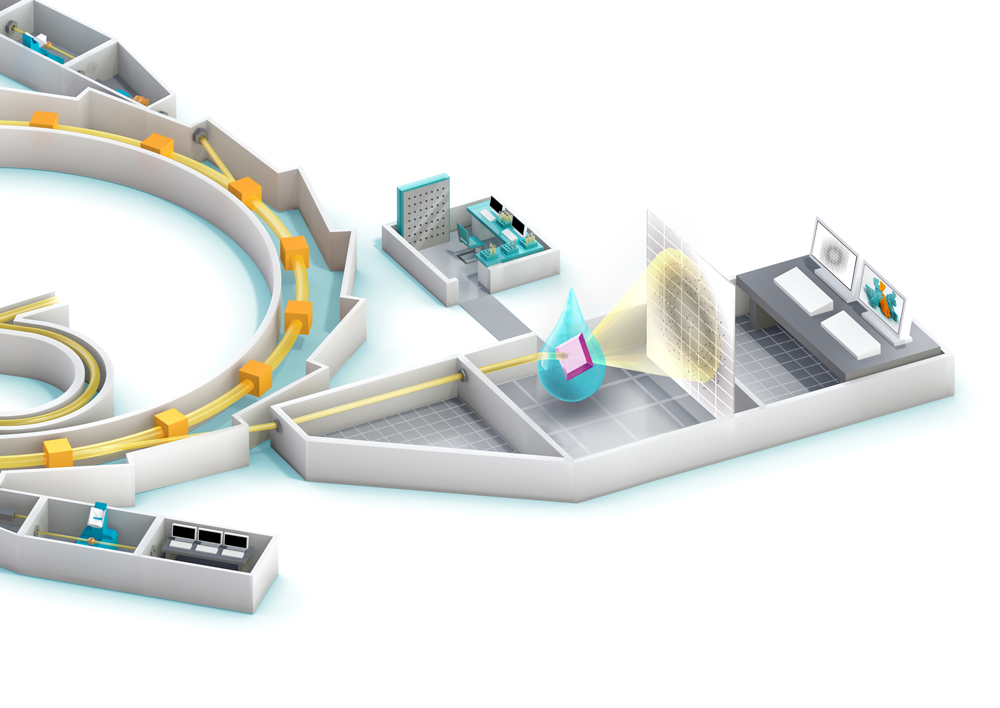

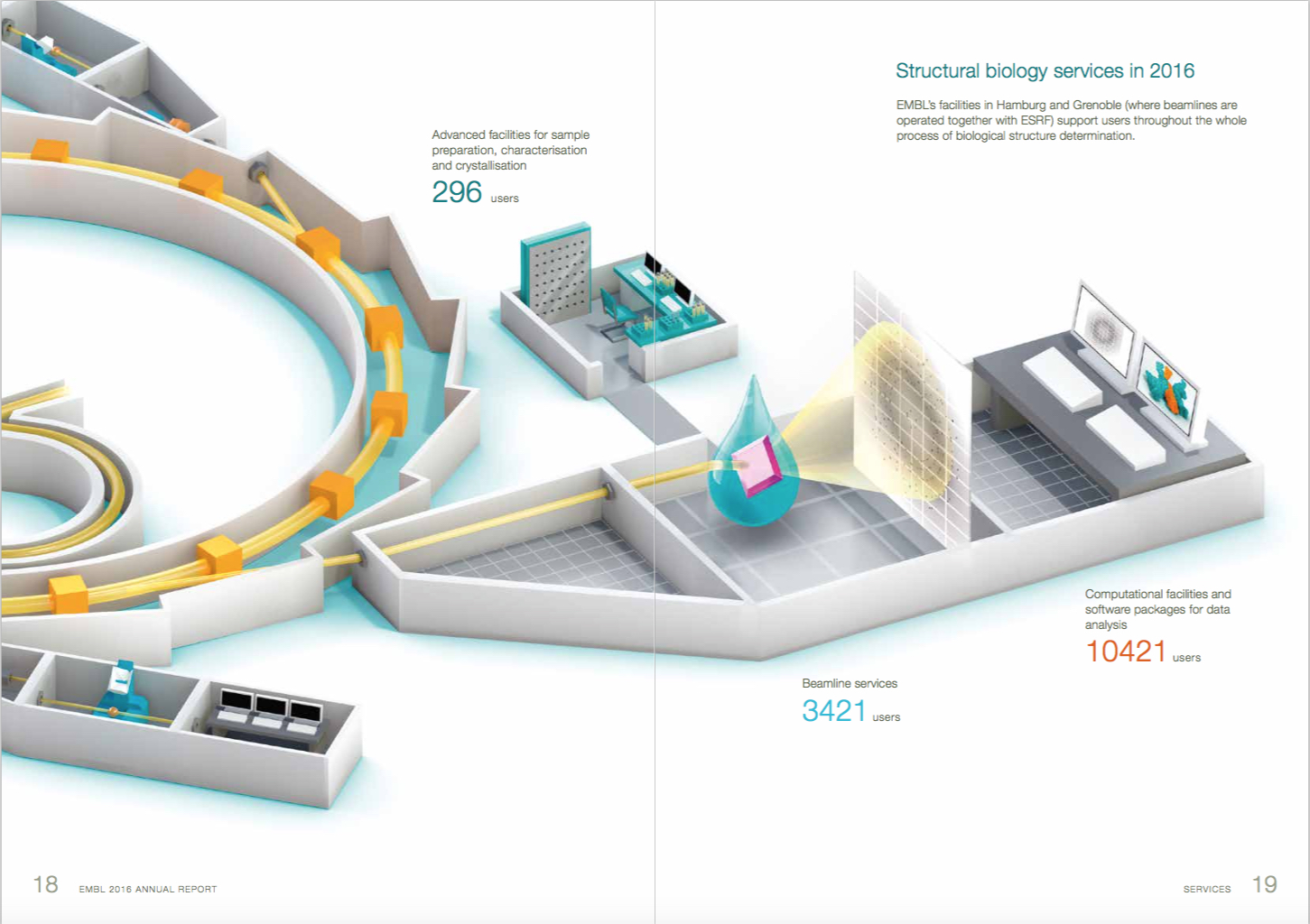

If a piece of core content is repurposable, it can also be used to tell several different stories. When we created this infographic, we thought of it as a pizza base that you can put different toppings on:

We used it in the Annual Report to show how EMBL supports the whole process of determining a protein’s structure:

If we change the text, this can become an explanation of how X-ray crystallography works. We can take the image of the computers and use it in a slide about the relevant software and databases developed and managed by EMBL scientists. Or someone else might find it useful to talk about something we haven’t yet thought of!

Another, related way of extending content’s lifespan is the ‘mix-and-match’ approach. This entails creating snippets of content that can be used individually or stitched together in different ways. It works very well for some of the institutional content we produce, for instance. We have a general ‘boilerplate text’ to describe EMBL. But if we’re telling Italian journalists about a discovery from EMBL Rome, it’s useful to be able to add on a little paragraph about that site in particular: a site boilerplate with specifics about research interests, what the site offers to scientists worldwide, what neighbours its scientists collaborate with on campus. That site boilerplate can also be used for recruitment purposes, but in those instances what you need to combine it with is a little paragraph extolling the virtues of its location: the vibrant university town, mountain air or seaside views.

This modular approach to content is also something that we’ve started to think of in the context of video. The result of our first attempt will be online soon – keep an eye out for it!

Making content future-proof

So how do you create content that will retain its usefulness against a backdrop of change? I’m still figuring this out, but based on my experience over the past year, a few things seem to help:

- Make it modular

See above. This also helps with number 4

- Avoid news pegs, be careful with pop culture references

It’d be a waste for your excellent explanation of gene editing to be rendered useless because no-one knows that song anymore.

- Embrace approximation

If you say ‘more than 20’, you won’t have to update when 22 changes to 23, or 23 changes to 25, etc.

- Make it as easy as possible to update

If paragraphs in a text don’t reference what came before, they can be replaced (or eliminated) much more easily. The same is true for elements in an image: right at the start of your project, think about what elements you may want to easily replace in the future.

- Anticipate future needs

I don’t know what stories EMBL will be publishing in five years’ time. But if I’m familiar with the institute’s strategy and our communication priorities, and have a feel for the upcoming trends in the field, I can predict topics that we’re likely to be touching on again and again. Armed with that knowledge, I can assess how useful a particular piece of content may be in the long run. After all, core content can only support future stories if those stories get told.

Managing core content

So what do I do as EMBL’s Core Content Manager? Well, I’m tackling some practical challenges, like how to store content in a way that everyone in our team – writers, designers, social media managers and more, split across two countries – can easily find what they need. Or how to keep track of where a piece of content is used, so that it can be updated if necessary. I’m developing a strategy to ensure that our core content is aligned with EMBL’s goals and needs. And of course, I’ve started producing long-lasting, repurposable content. This means I’m exploring all sorts of different formats – from texts to infographics to animations – and how each can best be used to help tell EMBL’s stories.