Skills for a scientific career

Several studies have shown that the skills developed during early career research training are relevant for careers in academia, industry R&D and many other areas. These studies generally focus on a range of skills and, for each skill, compare the level of skill needed in the current role to the level to which this skill was acquired during the PhD (see e.g. here or here).

To add to this existing data, and aid evidence-based career guidance for life scientists, the EMBL Fellows’ Career Service launched a survey at the end of 2020 focused on what competencies [knowledge and behaviours] are used most by (former) life scientists working in a wide range of academic and non-academic careers. There were two major aims of the survey. Firstly, to validate a competency framework focused on ‘classical’ research careers; and secondly to map a modified version of the framework to other career areas and help scientists to identify careers that match their strengths.

We received 350 responses including researchers in a range of academic (120 responses) and industry R&D (38 responses) roles; as well as over 220 scientists working in a diverse array of non-research roles from clinical trial management to technology transfer.

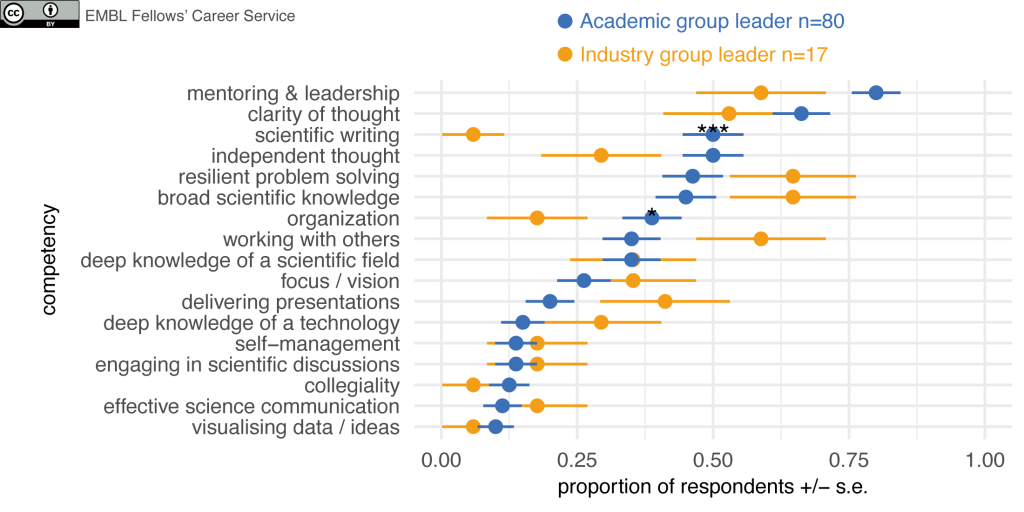

As outlined below, in these responses we did see differences in the competencies selected from respondents working in different career areas, with some statistically significant differences evident between the most well-represented careers (e.g. group leader roles in academia and industry).

Updated summary of responses

UPDATE: Following an additional call for non-research responses when we released this post in 2022, we now have 452 responses to our survey (126 from a range of PI and non-PI academic roles; 63 from early career researchers; 44 from industry R&D; and 282 from non-research roles) – a more detailed analysis of the 452 responses are summarized in a document here.

Most commonly used competencies

Respondents were asked to select a maximum of six competencies that they use most in their role. They could select from a list of 17 competencies. This set of competencies was identified through interviews with EMBL group leaders in the frame of ‘classical’ research careers and can be seen in Figure 1.

For respondents in non-research-group-leader roles, the same 17 competencies were included, but some descriptions were adapted to provide a broader description (e.g. ‘scientific writing’, replaced with simply ‘writing’).

Not unexpectedly, there was a lot of variation in competencies selected, even with the same career area. Several respondents also noted in the comments that they are using many of the competencies they learned as a PhD + postdoc on a daily basis, making choosing just six difficult.

The five most commonly selected competencies for research group leaders (in academia + industry combined) were:

- Mentoring/leadership (selected by 77% of group leaders)

- Clarity of thought (63%)

- Resilient problem solving (50%)

- Broad scientific knowledge (49%)

- Independent thought (47%)

Comparing types of non-research-group-leader roles, we also saw some trends; scientists in science administration & management roles, for example, more frequently selected ‘organization’ as a top competency compared to scientists in other non-group leader roles. Further responses would, however, be needed to confirm the specific trends observed. For scientists who were not working as research group leaders, the top five competencies were:

- Effective communication (selected by 58%)

- Team-work (51%)

- Organization (48%)

- Broad scientific knowledge (41%)

- Resilient problem solving (39%)

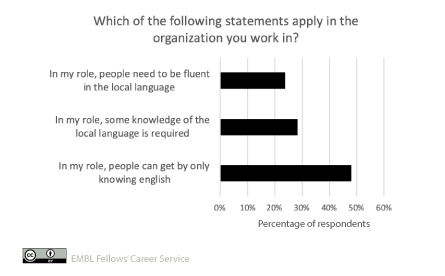

Language knowledge can be an asset in Europe.

Many academic labs work and publish in English. It is therefore not unusual to find highly mobile early-career researchers working in English-speaking labs in countries where they do not speak the local language. We therefore asked a specific question on language knowledge in the survey.

198 respondents were working in a country where English is not the local language (mostly within Europe). Of those, 48% said that for their role you could get by with just a knowledge of English, 28% needed some knowledge of the local language, and 24% needed to be fluent in the local language.

For those working as academic group leaders, only 18% stated that they needed to be fluent in the local language. The distribution of these respondents implies that there is a lot of variation depending on the individual institution – and that this is likely influenced by the country and type of institution/position. In particular, in some cases, academic group leaders may be expected to teach in the local language. Of the 14 respondents who stated that at least some teaching experience is required to be hired as a junior group leader at their institution, 50% said group leaders need to be fluent in the local language.

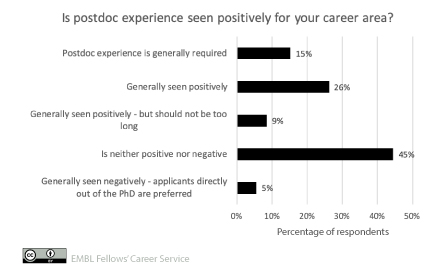

Postdoc experience is often seen neutrally for employment outside academia.

Several articles have been published that advise PhDs only to consider a postdoc position if they want to be a group leader (e.g. here, here).

These articles quite rightfully point out that, for careers where postdoc experience is not required, pursuing a postdoc position will delay your entry into your long-term career and this can have further implications (e.g. lower life-time earnings). Additionally, some non-academic hiring managers and recruiters tell us that, during the application process, senior postdocs will need more clearly demonstrate their adaptability and motivation to move to a new career area than recent PhD graduates.

Nevertheless, our survey data suggest that postdoc training will, in most cases, not make your CV less attractive, and may even be seen positively in some cases: for the 164 survey respondents not working as a postdoc or research group leader, only 5% said that applicants directly out of the PhD are preferred. The most common response (45%) was that a postdoc is neither positive or negative, 26% stated that postdoc experience is seen positively for their role. Postdoc experience was considered a requirement for 15% of respondents overall, including for more than 50% of respondents working in academic teaching, in research infrastructure leadership (in academia or industry), and in science publishing.

.