Guest post: Snakemake Input Functions by Tim Booth

Workflows can get really complex

If you turn your entire analysis project into a Snakemake workflow, you may end up with something like this.

Sometimes, the standard Snakemake wildcard matching logic is not enough to express the connections you need to make, especially with complex combining steps. In these cases we can use input functions. Before seeing how these work, we need to talk about Python functions in general.

Python functions in general

You’ve likely made use of utility functions like expand() and glob_wildcards() in writing Snakefiles. These are actually Python functions, but you don’t really need to know this to make use of them. Writing your own function requires more Python syntax knowledge, so here is a quick refresher on how they work.

Functions in Python look like this:

def myfunc(arg1, arg2):

"""Return a pair greetings for the two individuals specified.

"""

result = expand( "Hello {x}", x = [arg1, arg2] )

return result

There are many things to note in these lines:

- The keyword

def, as well as the parentheses and the colon, are always used when defining a Python function - As with rules, the function has a name of our choosing –

myfunc - The function has arguments, ie. placeholders for values to pass in, which are also named –

arg1andarg2 - The function body is indented and consists of one or more Python statements to be run when the function is called

- It’s good practice to put a comment at the top, saying what exactly this function does

- The body may set local variables – here

result– which can only be referenced within the function - Other functions may be called within the function body – here

expand() - The keyword

returnexits the function with a result

The simplest way to test the function is to put it in a file and run it with Snakemake. We’ll use a couple of print() lines to call the function and show the result.

# Save as myfunc_test.py then run "snakemake -n -s myfunc_test.py"

def myfunc(arg1, arg2):

"""Return a pair greetings for the two individuals specified.

"""

result = expand( "Hello {x}", x = [arg1, arg2] )

return result

print( myfunc("you", "me") )

print( myfunc("everyone here", "nobody in particular") )

Having put the above lines into myfunc_test.py, we see that each time the function is called it produces a 2-item list, lists of things being denoted by square bracket notation. Since there are no rules in this file, Snakemake has nothing to put in the DAG and so it stops after running the two print() statements.

$ snakemake -n -s myfunc_test.py

['Hello you', 'Hello me']

['Hello everyone here', 'Hello nobody in particular']

Building DAG of jobs...

Nothing to be done.

Note

You could also run the above file directly in Python –

$ python3 myfunc_test.py– but to make it work you’d also need to add the line:

from snakemake.io import expandto the top. When the code is run via Snakemake this utility function, among other things, are imported for you.

Input functions in Snakemake

Snakemake’s usual way of calculating the inputs to a rule involves plugging wildcards into fixed templates. In most cases, you can (and should) use carefully chosen file naming to make this work, but in some cases, there is no way to do it while keeping the rule generic.

A typical example would be a combining rule where the number of things to combine is not fixed. Imagine we had these input files.

$ tree reads/

reads/

├── control_A

│ ├── r0.fasta

│ └── r1.fasta

├── control_B

│ ├── r0.fasta

│ └── r1.fasta

├── high_conc

│ ├── r0.fasta

│ ├── r1.fasta

│ ├── r2.fasta

│ └── r3.fasta

└── low_conc

├── r0.fasta

├── r1.fasta

├── r2.fasta

└── r3.fasta

And we want to merge them by sample.

rule merge_reads_for_sample:

output: "merged_{sample}.fasta"

input: expand("reads/{{sample}}/r{n}.fasta", n=[0,1,2,3])

shell:

cat {input} > {output}

This rule will work for the high_conc and low_conc samples but for the control samples Snakemake will complain about missing input files. We need a different expansion depending on the value of {sample}, and this is what an input function can do for us.

def i_reads_for_sample(wildcards):

"""Input function for merge_reads_for_sample rule. Our control libraries

have 2 reads and the others all have 4.

"""

sample_name = wildcards.sample

if sample_name.startswith("control_"):

reads_in_sample = [0,1]

else:

reads_in_sample = [0,1,2,3]

return expand("reads/{sample}/r{n}.fasta", sample = sample_name,

n = reads_in_sample)

rule merge_reads_for_sample:

output: "merged_{sample}.fasta"

input: i_reads_for_sample

shell:

cat {input} > {output}

Looking at this line by line:

- The function is named

i_reads_for_sample.- I prefer to prefix my input functions with

i_but this is not a widespread Snakemake convention - The function has to be defined before the rule

- All input functions take a single argument which is conventionally named

wildcardsorwc

- I prefer to prefix my input functions with

- The value from

wildcards.sampleis copied to a local variablesample_name- An

if/elsestatement is used to work out the correct number of reads for this particular sample

- An

- Finally, the

expand()function gives the full list of input files needed for this sample- Note that I have had to explicitly add

sample = sample_namehere in the expansion as Snakemake will no longer fill this in for me.

- Note that I have had to explicitly add

- The rule now has the line

input: i_reads_for_sample. Note there are no parentheses or quotes but just the bare function name.

The example is a little contrived but illustrates all the key points. When Snakemake reads the rule definition it saves a reference to the function but does not call it yet. Only once it goes to make the rule into a job, and therefore knows the wildcard values from that job, does it actually call the function to get the real input files. Any rule may be used to construct multiple workflow jobs and Snakemake calls the input function for each of these jobs. Contrast this with the first definition of the rule where the expand(...) expression would be evaluated immediately, and only once, to make a fixed input template.

In a real workflow, we might put some more flexible logic into the function such as using glob_wildcards() to dynamically scan for input files per sample, or have a config file to set the number of inputs per sample. The input functions can get as complex as you need, and incorporate any amount of Python logic.

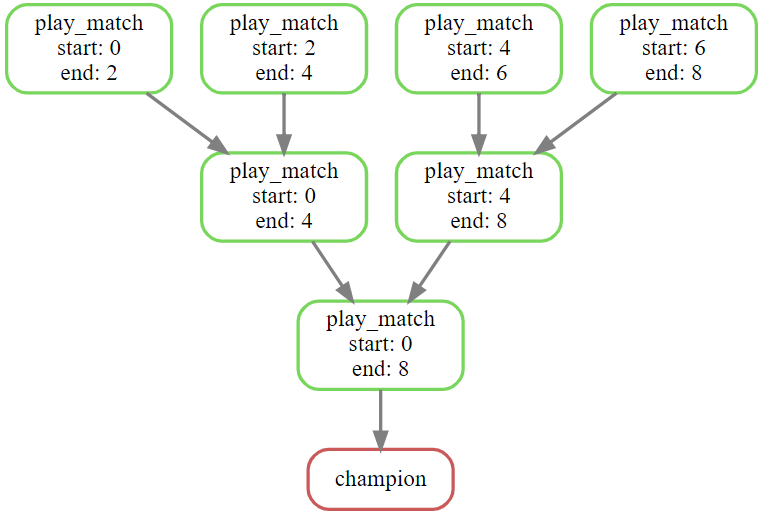

Making a tournament bracket with input functions

We’ll now show the power of input functions by doing something less common but more interesting. The idea is that we need to combine a big list of files but this time our combiner application can only merge two files at once, for some reason. We need to adopt a recursive strategy where we merge pairs of files, then merge the results, and keep going until we have a single final result. And this should all be realised as a Snakemake DAG so that Snakemake can run jobs in parallel, resume partial runs, etc.

It turns out this logic is analogous to running a tournament bracket, where rather than merging the pairs of inputs we pick the “winner” from each pairing until we get a final “champion” result. So we’ll generate a collection of “top trumps” cards, then play a knockout tournament to find the winner. Unlike the previous section, this is a full example that you can run for yourself (download the python scripts below).

First, generate our “top trumps” player cards.

$ ./generate_cards.py 8

Generating 8 cards in ./all_cards/

DONE

$ ls all_cards

card_1.json card_3.json card_5.json card_7.json

card_2.json card_4.json card_6.json card_8.json

$ cat all_cards/card1.json

{

"Name": "Gil Annor",

"Speed": 140,

"Endurance": 4.2,

"Power": 93,

"Skill": 31

}

You’ll see a different name and stats as the generator is randomised. Now we can match any two of these players to see who wins.

./play_a_match.py all_cards/card_1.json all_cards/card_2.json

Matching Gil Annor vs Kennel Timwick.

The criterion is: Highest Skill.

Winner is Kennel Timwick with 79 vs 31.

{

"Name": "Kennel Timwick",

"Speed": 120,

"Endurance": 7.4,

"Power": 60,

"Skill": 79

}

The match-up script simply picks a random category, compares the corresponding values and prints out the winning card, so how do we get Snakemake to orchestrate a tournament of multiple matches for us? The idea is to use a recursive algorithm where the tournament of 8 is split into two sub-tournaments of 4, and each of these in turn is two sub-sub-tournaments of 2. Of course, a tournament of 2 is simply a single match, so this is the base case. If we have all the players in a list, it looks like this, because Python lists count from 0:

players = [ "card_1", # index 0

"card_2", # index 1

"card_3", # index 2

"card_4", # index 3

"card_5", # index 4

"card_6", # index 5

"card_7", # index 6

"card_8" ] # index 7

The players could be listed in any order, and the order of the list determines how the player cards are paired up in the tournament. By the Python convention of sub-list indexing we’ll call the match between card_1 and card_2 [0:2], the match between card_3 and card_4 [2:4], and the match between the winner of those is [0:4]. Then the other semi-final is [4:8] and the very final match is [0:8]. This scheme works for any number of starting cards. The logic this leads us to is:

# Pseudo-code for building the tournament plan.

# Starting with the final, range=[0:8], recurse back until we hit first round matches

player_count = range_end - range_start

if player_count > 2:

# This is a final or semi-final. Find the midpoint of the list and generate 2 sub-ranges,

# then recurse. Eg. for [0:8] we play the winners of [0:4] and [4:8].

midpoint = mean of range_start and range_end

match winner of match [{range_start}:{midpoint}] vs.

winner of match [{midpoint}:{range_end}]

else:

# This is first-round match between two players

match players[range_start] vs.

players[range_start+1]

This idea will work for 8, 16, 32, players etc. We can handle all the cases where the number is not a power of 2 by adding a third condition.

# More pseudo-code

if player_count == 3:

match winner of match [{range_start+1}:{range_end}] vs.

players[range_start]

This resolves a range like [0:3] by playing two of the players against each other and then matching the third one against the winner. The effect is that some of the players will get a bye in the first round of the tournament if there are not 2n players. The total number of matches in the tournament will in all cases be one fewer then the total number of players.

Because every tournament match is now uniquely identified by two numbers, we can save the results of every match into a file named matches/{start}-{end}.json. The champion will be saved to matches/0-8.json, or whatever number corresponds to the length of the list of players.

And so here is the final Snakefile implementing these ideas. I’ve added a glob() expression to scan for the input files, a driver rule to show the winner, and a rule to play individual matches. I’ve translated the pseudo-code above into working Python and put it into an input function.

from glob import glob

# Each "player" is one top trumps card, represented as a JSON file.

ALL_PLAYERS = sorted(glob("all_cards/card_*.json"))

assert len(ALL_PLAYERS) > 1, "Run generate_cards.py to make some input files."

def i_play_match(wildcards):

"""Given start and end indexes, work out the matches that must be played

to resolve this part of the tournament bracket.

"""

# Find the range from "matches/{start}-{end}.json"

range_start = int(wildcards.start)

range_end = int(wildcards.end)

player_count = range_end - range_start

# Sanity check. We should always have at least 2 players here.

assert player_count >= 2

if player_count == 2:

# First round match between two input card files

return [ ALL_PLAYERS[range_start],

ALL_PLAYERS[range_start+1] ]

elif player_count == 3:

# Only occurs if len(ALL_PLAYERS) is not a power of 2

# Match the second and third players and give the first a bye to the second round.

return [ f"matches/{range_start+1}-{range_end}.json",

ALL_PLAYERS[range_start] ]

else:

# Given four or more players to match up, split the range to trigger recursion

midpoint = range_start + (player_count // 2)

return [ f"matches/{range_start}-{midpoint}.json",

f"matches/{midpoint}-{range_end}.json" ]

# Default rule to crown the final winner

rule champion:

input: "matches/0-{}.json".format(len(ALL_PLAYERS))

shell:

"echo 'And the winner is...' ; cat {input}"

rule play_match:

output: "matches/{start}-{end}.json"

input: i_play_match

shell:

"python3 play_a_match.py {input[0]} {input[1]} > {output}"

And we run it:

$ snakemake -F -j1

...

Job counts:

count jobs

1 champion

7 play_match

...

And the winner is...

{

"Name": "Congal Anndelwick",

"Speed": 131,

"Endurance": 3.4,

"Power": 57,

"Skill": 96

}

...

Well done, Congal Anndelwick! Having played a tournament of 8 players, we can generate a bunch more cards to put the workflow through its paces, and we can try using the -j flag to run early rounds in parallel. On my laptop, a tournament of 250 takes around 15 seconds, but this drops to 5 seconds by using -j 8. Of course, most of the time here is spent starting and stopping the Python interpreter. If the matches were actually taking real time to process, for example by simulating a game between the players rather than just comparing numbers, the advantage of running in parallel could be very significant.

Credits

Timothy Booth, Edinburgh Genomics (https://genomics.ed.ac.uk)

This post incorporates content created under the Ed-DaSH project UKRI grant MR/V039075/1