Michael Dorrity

Group Leader

michael.dorrity [at] embl.de

ORCID: 0000-0002-7691-6504

EditEnvironmental response at the single-cell level

Group Leader

michael.dorrity [at] embl.de

ORCID: 0000-0002-7691-6504

EditEffects of environmental stress are variable, with some individuals more sensitive than others. This variability obscures the influence of the environment during development, limits our understanding of genotype–phenotype relationships, and leaves us unable to predict how different species will respond to a changing environment.

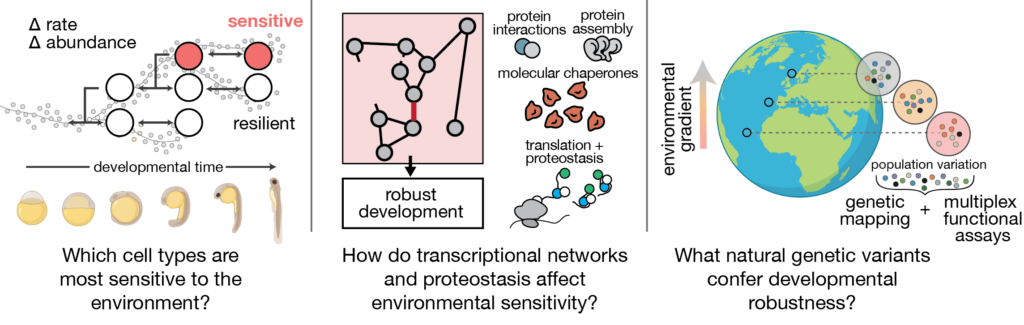

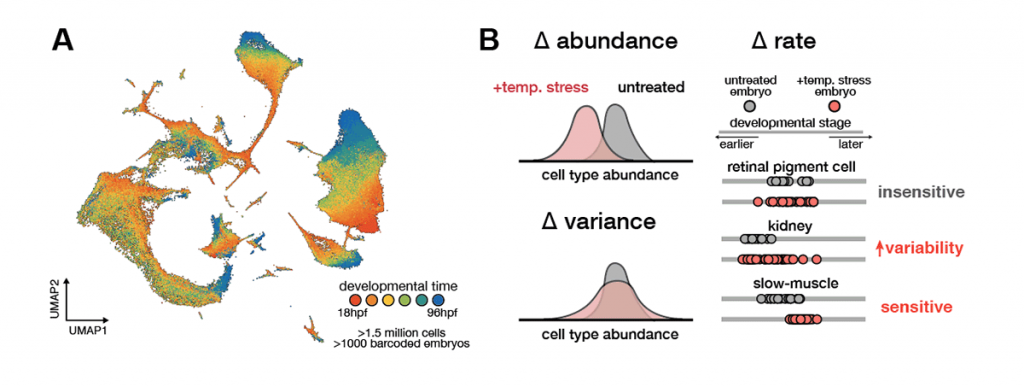

To better understand how environmentally induced variability propagates across scales, our lab uses single-cell genomics as a phenotyping tool to capture cell- and organism-level processes alongside molecular phenotypes in ectotherms. We adapt this approach in different fish species, capturing multiscale phenotyping data for hundreds to thousands of individuals to build an average “embryo trajectory” and to quantify reproducibility in development. Using computational and statistical approaches to partition variability at different levels (molecular, cellular, and organismal), we define sources of environmental sensitivity and uncover mechanisms of adaptation. We then validate and explore these mechanisms experimentally using classical developmental genetics, gene editing and time-resolved imaging.

The environment can challenge the embryo’s capacity to coordinate responses across cells. Our previous work has shown that raising zebrafish embryos in elevated water temperatures has profound effects on the programme of development: cell types proportions are altered in the embryo, specific cell types show increased variability across individuals, and development accelerates non-uniformly across cell types. This differential acceleration introduces asynchrony that limits reproducibility of development. These findings reveal how a global perturbation like temperature nevertheless induces cell type-specific effects that underlie whole-animal phenotypes.

At the molecular level, temperature sensitivity is linked to mechanisms of proteostasis–the maintenance of folding, synthesis, and degradation of proteins. While biochemical mechanisms of proteostasis control are well-understood, their differential activity across cell types during the course development is not. We focus on two questions: (1) How do cell type-specific differences in proteostasis affect temperature sensitivity in the embryo? (2) Does control of proteostasis influence developmental rate? We combine single-cell genomics and high-throughput biochemistry to define the parameters that drive sensitivity of different cell lineages, with a long-term goal of engineering increased reproducibility of developmental processes.

We use experimental and computational approaches to understand links between temperature sensitivity, developmental timing, and the reproducibility of embryogenesis. Our projects include: