Lost in the labyrinth

Decoding the instructions that tell cells how to become blood

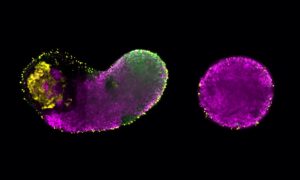

Blood cells have limited lifespans, which means that they must be continually replaced by calling up reserves and turning these into the blood cell types needed by the body. Claus Nerlov and his colleagues at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) unit in Monterotondo, Italy, in collaboration with researchers from Sten Eirik Jacobsen’s laboratory at the University of Lund in Sweden, have now uncovered how an intracellular communication pathway contributes to this process. Because defects in such pathways and in the development of stem cells frequently lead to leukemia and other diseases, the work should give researchers a new handle on processes within cells that lead to cancer. The work is published in this week’s online issue of Nature Immunology.

Over the past decades, molecular biologists have identified several pathways – sequences of molecules which manage the flow of information within the cell – responsible for major biological processes. One of these, the ‘Wingless’ pathway, plays a vital role in shaping tissues and organs in developing embryos of nearly all animal species. It also helps organisms manage stem cells, by keeping them on hold and preventing their differentiation until the right time. Such pathways are usually switched on and off by external stimuli that help cells respond properly to the environment. Now Peggy Kirstetter and other members of Nerlov’s lab have shown what happens when Wingless is too active in hematopoietic stem cells in mice.

“We modified one element of the pathway, a protein called ‘beta-catenin‘, so that it was stuck in ‘transmission mode’,” Kirstetter says. “This created cells in which the pathway was always switched on. We’ve known that Wingless contributes to blood differentiation, but didn’t know how the signals were being transmitted within the hematopoietic stem cell.”

The modified protein had dramatic effects. Usually, most cells undergo numerous transitional stages on their way from stem cells to fully-developed types in the blood. Several types of blood cells vanished entirely; the same thing happened to more basic cell types higher up in the blood lineage hierarchy. Particular kinds of stem cells disappeared from the bone marrow of the mice. Others were too frequent. Bone marrow cells didn’t develop into myeloid and red blood cells. B- and T-cells were also blocked at early stages, but in a different way. This hints that they may be controlled by other protein links in the Wingless pathway as well. Perhaps most strikingly, beta-catenin appears to make cells take decisions about their fate before they leave the stem cell compartment in the bone marrow, something so far not thought to occur.

The study proves that beta-catenin plays a central role in determining whether blood cells form or not. On the other hand, an overactive Wingless pathway doesn’t seem to damage cells that already exist. Thus beta-catenin seems to be a decision-maker, a selector of how information gets routed within the cell, rather than something which maintains the vitality of existing cells.

Nerlov compares the breakdown to people standing at a fork in a labyrinth, hesitating before they go on. “We know there are strong connections to cells’ decisions to divide, to develop or to die. If cells don’t commit themselves to the right developmental path at the right time, they’re very likely to die or to begin an inappropriate type of reproduction. Acute leukemias and other forms of cancer cells derive from defects such as this. Understanding the processes by which they form will require pinpointing the forks in the road where things go wrong.”