Modern brains have an ancient core

Multifunctional neurons that sense the environment and release hormones are the evolutionary basis of our brains

Hormones control growth, metabolism, reproduction and many other important biological processes. In humans, and all other vertebrates, the chemical signals are produced by specialised brain centres such as the hypothalamus and secreted into the blood stream that distributes them around the body. Researchers from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) now reveal that the hypothalamus and its hormones are not purely vertebrate inventions, but have their evolutionary roots in marine, worm-like ancestors. In this week’s issue of the journal Cell they report that hormone-secreting brain centres are much older than expected and likely evolved from multifunctional cells of the last common ancestor of vertebrates, flies and worms.

Hormones mostly have slow, long-lasting and body-wide effects, rendering them the perfect complement to the fast and precise nervous system of vertebrates. Also insects and nematode worms rely on the secretion of hormones to transmit information, but the compounds they use are often very different from the vertebrate counterparts.

“This suggested that hormone-secreting brain centres have arisen after the evolution of vertebrates and invertebrates had split,” says Detlev Arendt, whose group studies development and evolution of the brain at EMBL. “But then vertebrate-type hormones were found in annelid worms and molluscs, indicating that these centres might be much older than expected.”

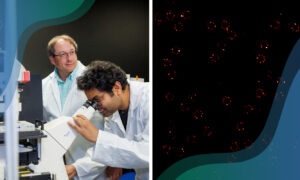

Scientist Kristin Tessmar-Raible from Arendt’s lab directly compared two types of hormone-secreting nerve cells of zebrafish, a vertebrate, and the annelid worm Platynereis dumerilii, and found some stunning similarities. Not only were both cell types located at the same positions in the developing brains of the two species, but they also looked similar and shared the same molecular makeup. One of these cell types secretes vasotocin, a hormone controlling reproduction and water balance of the body, the other secretes a hormone called RF-amide.

Each cell type has a unique molecular fingerprint – a combination of regulatory genes that are active in a cell and give it its identity. The similarities between the fingerprints of vasotocin and RF-amide-secreting cells in zebrafish and Platynereis are so big that they are difficult to explain by coincidence. Instead they indicate a common evolutionary origin of the cells. “It is likely that they existed already in Urbilateria, the last common ancestors of vertebrates, insects and worms” explains Arendt.

Both of the cell types studied in Platynereis and fish are multifunctional: they secrete hormones and at the same time have sensory properties. The vasotocin-secreting cells contain a light-sensitive pigment, while RF-amide appears to be secreted in response to certain chemicals. The EMBL scientists now assume that such multifunctional sensory neurons are among the most ancient neuron types. Their role was likely to directly convey sensory cues from the ancient marine environment to changes in the animal’s body. Over time these autonomous cells might have clustered together and specialised forming complex brain centres like the vertebrate hypothalamus.

“These findings revolutionise the way we see the brain,” says Tessmar-Raible. “So far we have always understood it as a processing unit, a bit like a computer that integrates and interprets incoming sensory information. Now we know that the brain is itself a sensory organ and has been so since very ancient times.”