Oskar’s structure revealed

The structure of two parts of the Oskar protein, known to be essential for the development of reproductive cells, has been solved by scientists from EMBL Heidelberg.

This advance – published today in Cell Reports – has also enabled the team to gather the first insights into how this poorly understood protein functions. The research was carried out with fruit flies, but has implications for other animals, as many organisms, including humans, also have part of the Oskar protein.

Named after the main character from Günter Grass’ novel The Tin Drum, who chose never to grow up, the Oskar protein is essential for development. Embryos that develop from fruit fly eggs lacking the normal amount of Oskar protein are unable to form germ cells – cells that allow reproduction – and so the resulting flies are sterile. Complete lack of the Oskar protein also prevents the embryo’s abdomen from forming normally which stunts its growth so it dies.

In a healthy egg Oskar initiates the formation of what’s known as the germ plasm – a gathering of proteins and RNAs within the cytoplasm, which then goes on to form a new germ cell. Germ plasm normally forms in a particular position within the egg, but if Oskar is artificially moved elsewhere, the germ plasm will form in the new location.

Solving the structure has enabled us to start to see how the different parts of the protein function at a molecular level.

Co-author of the paper, Anne Ephrussi said: “While we’ve known Oskar’s genetic role in development for some time, we’ve not known the mechanism by which this takes place. Solving the structure has enabled us to start to see how the different parts of the protein function at a molecular level, which could help us to understand more about this stage of development in a wide range of organisms.”

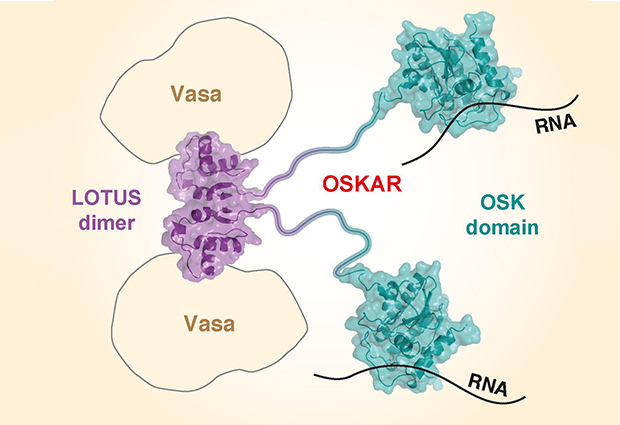

Using X-ray crystallography, carried out in collaboration with the lab of Christoph Müller, the team was able to determine for the first time the structure of Oskar’s two domains, called OSK and LOTUS. The OSK domain is found in some insects, including the fruit fly and the mosquito. The LOTUS domain is more widespread, being found in bacteria, plants and animals, including mice and in humans.

Using experiments with fruit fly eggs, the team saw that Oskar binds to RNA within the cell – specifically three RNAs derived from genes also known to be important to germline development. But when they looked in more detail, they found that it was only the OSK domain that binds to RNA.

The LOTUS domain – which they expected to bind to RNA – didn’t in fact do so. Instead, the team found that LOTUS binds to an enzyme called Vasa helicase, which is also one of the essential initial ingredients of the germ plasm.

It could be that this interaction isn’t specific to the fruit fly but also takes place in other germline cells.

“Vasa, like LOTUS, is widely found in other organisms, including animals, so it could be that this interaction isn’t specific to the fruit fly but also takes place in other germline cells,” says co-researcher, Mandy Jeske. “There is still much to learn about how the Oskar protein functions – for example we don’t know yet if LOTUS just binds to Vasa or if it also controls Vasa’s activity. This work has opened up lots of exciting new avenues for investigation.”