Stephen Cusack: what I’ve learned

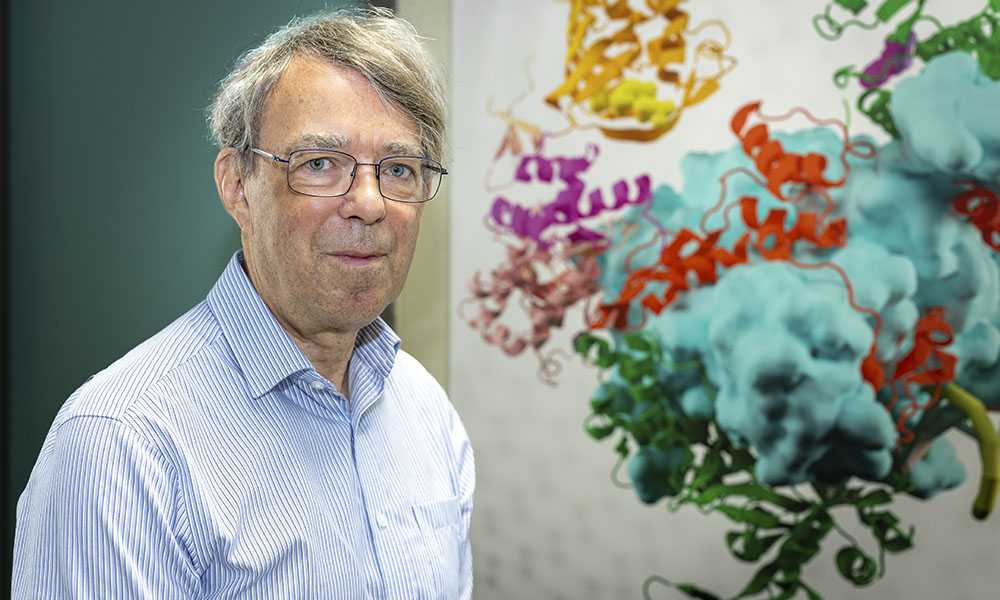

Stephen Cusack, world-renowned structural biologist and former Head of EMBL Grenoble, reflects on his early influences, his achievements, and the lessons he’s learned as he embarks on his next adventure

When asked about the people who influenced his scientific career, Stephen Cusack always begins by talking about his parents. Starting his career as a theoretical physicist, Cusack obtained his PhD at the Imperial College London, following in the footsteps of his father – a physics professor. But during his postdoctoral work, Cusack switched to biology, aligning more closely with his mother’s career as a biology teacher and the family’s love of wildlife.

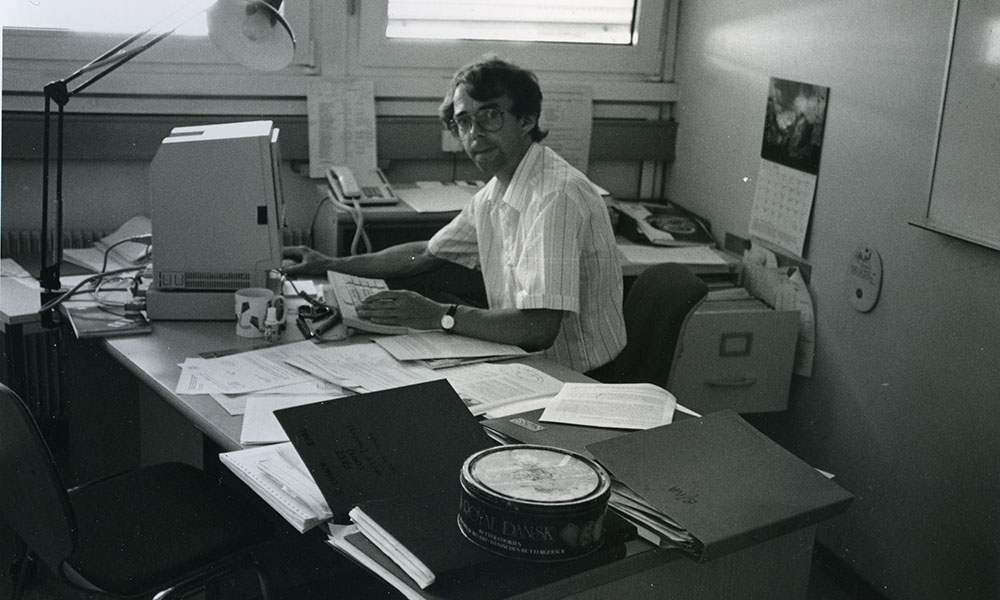

Joining EMBL Grenoble (the Grenoble ‘outstation’ as it was known then) as a postdoctoral fellow in 1977, Cusack started working with Bernard Jacrot, who was the second Head of the institute. Jacrot introduced him to the study of virus structure and had a major influence on his early career.

Being somewhat dissatisfied with doing small-angle neutron scattering on whole plant viruses and later on the influenza virus, Cusack decided to follow the advice of Tom Blundell, a well-known structural biologist in the UK, who suggested X-ray crystallography might be more informative. To learn this technique, Cusack took a sabbatical in Don Wiley’s Lab at Harvard University in 1985. This would turn out to be a major turning point in his career.

These early influences directed Cusack toward viruses, structural biology, and X-ray crystallography, leading him to take advantage of what was happening at the time in Grenoble. The world’s first third-generation synchrotron was built in Grenoble during the early 1990s and Cusack directed EMBL Grenoble towards developing automated technologies to exploit the uniquely high X-ray flux for protein crystallography. This would benefit not just the Grenoble site, but structural biologists throughout Europe.

Among the Cusack group’s biggest achievements is its work on RIG-I, the innate immune receptor which recognises when you are infected with an RNA virus. It detects ‘non-self’ features of RNA specific to a virus, triggering an anti-viral immune response. “When I first heard about this, I thought, ‘This is amazing, how can it tell the difference between viral and human RNA?’” Cusack recalled.

The team established the structure of RIG-I in 2011, work carried out by Eva Kowalinski, then a PhD student in the group. It explained the mechanism of how binding of a particular viral RNA structure to RIG-I triggered the signalling cascade that led to the innate immune response, a problem many competing groups were trying to solve at the time.

Another major breakthrough was obtaining the crystal structure of the influenza polymerase. After many years of effort, Stephen and his team determined the structures of both influenza A and B polymerases in 2014 resulting in two back-to-back papers in Nature.

In addition to running his research group, Cusack was appointed Head of EMBL Grenoble from 1989 until 2022. Under his leadership, EMBL Grenoble contributed to world-leading technology development for synchrotron-based structural biology research. This was carried out in a long-standing and mutually beneficial collaboration with the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), through the creation of the EMBL-ESRF Joint Structural Biology Group (JSBG).

He also was one of the founders of the Partnership for Structural Biology which integrated the structural biology activities of the EMBL, ESRF, the Institut de Biologie Structurale (IBS), and the Institut Laue Langevin (ILL), and one of the initiators, together with Sir David Stuart and others, of the Europe-wide research infrastructure Instruct. These enduring partnerships have contributed to a successful atmosphere of scientific collaboration locally and internationally.

Since retiring, Cusack continues to produce new scientific results with his small team and with collaborators. For 2024-2025, he will stay on as an Emeritus at EMBL, while also joining Oxford University as a visiting professor. We took this opportunity to catch up with him regarding the lessons learned during his long scientific career.

Here, in his own words, are the key insights and bits of wisdom that have emerged during his years in science.

Structural biology and the future of discovery

As a structural biologist, seeing new structures for the first time is very exciting. They slowly emerge on the screen as you work, and you realise you’re the first person in the world to see this structure. It’s even better when you can gain some important biological insights from the structure you’ve determined.

I would never get tired of this thrill of discovery. But determining the structure is only the beginning. Ten years after obtaining the first structure of the complete influenza polymerase, we are still working on it and keep discovering new things about how it works.

Nowadays, if I were to start again, I would still be a structural biologist. Maybe I would be working on in situ structural biology, observing what’s happening directly inside the cell. Structural biology is moving in the direction of being able to do that through cryo-tomography and other techniques, but it is not yet clear how far you can go.

Structural biology is still incredibly important for understanding how life’s processes work, as it provides the link from chemistry and physics to higher-order organisation. This broad view across scales – from molecules to cells and so on – pushed by EMBL for a long time but particularly in its current scientific programme, is the way to do it.

Artificial intelligence can help us put all the data together into a big picture, with enormous impacts on research and medicine. AlphaFold is a fantastic new structure prediction tool for structural biologists (and others) and it is getting more and more powerful with each new release (AlphaFold3 only a few weeks ago). However, it does not change anything about the fundamental discovery and validation process, it simply helps you get to the next step quicker.

Life at and outside EMBL

Cells and living things are very complicated; at times it’s difficult to grasp, even to conceive how life works so robustly such that living things can not only exist but thrive.

EMBL has changed a lot. When I first came to EMBL Grenoble, the organisation was a very small place and everyone knew each other. Now, you don’t know a tenth of what’s going on! It’s enormous, with a broad spectrum of activities, and sometimes you can feel a bit lost.

We created two traditions at EMBL Grenoble: the Christmas Lunch and the Lab Ski Day. I made sure these happened every year. We started the Lab Ski Day in the 1990s, and only skipped 2021 when ski stations were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Bringing people together outside the lab is important, and my successor has kept up the tradition.

Apart from science, I’m primarily interested in wildlife, the living world, and music. A favourite place around Grenoble is the Haut Plateau of the Vercors. Along the cliffs on the eastern edge, you can look over Grenoble and basically see the whole of the French Alps. Another favourite walk is to the Source de la Romanche in the Parc National des Ecrins.

On science and leadership

Scientifically, you need to have challenges. For the influenza polymerase, it took many years before we could even do any structural analysis. That’s what science is all about, going for important but challenging problems, not giving up, and finding solutions to roadblocks.

It is important to have some kind of vision, to know the direction you want to go in. I have seen this in action both in my own research and as Head of EMBL Grenoble. One of my mentors was Lennart Philipson, former EMBL Director General, who advised me to think about where I want to be in 5-10 years and then map a path to get there.

Scientists think about their science all the time. You never stop. It’s why I like going to the mountains. It’s beautiful and relaxing, but also it opens your mind. I always found that seeing Nature spontaneously brings forward new ideas.

As a scientist, you need to be curious, determined, adventurous, and take risks, and not shy away from bigger challenges.

Young scientists can and should broaden their vision. I’d say, get interested in different aspects of research, go to seminars, ask questions, and make sure your view of the field stays broad. If you’re too focused on your own project, you’ll miss connections to other important things.

You can’t do everything by yourself. You need to surround yourself with good people and build up a motivated and engaged team; that’s critical. Ultimately, this is what determines success.

Credit: Edith Heard/EMBL