Celebrating excellence

It’s the one time of year when the EMBL community gets together in one place to celebrate scientific achievements, the Laboratory’s unique spirit, and draw inspiration from friends and colleagues. And one of the highlights of Lab Day, which took place on 10 July, is where EMBL celebrates the very special work of alumni through the John Kendrew and Lennart Philipson awards. We caught up with this year’s winners to find out more.

By Rosemary Wilson and Adam Gristwood

Science, society & serendipity

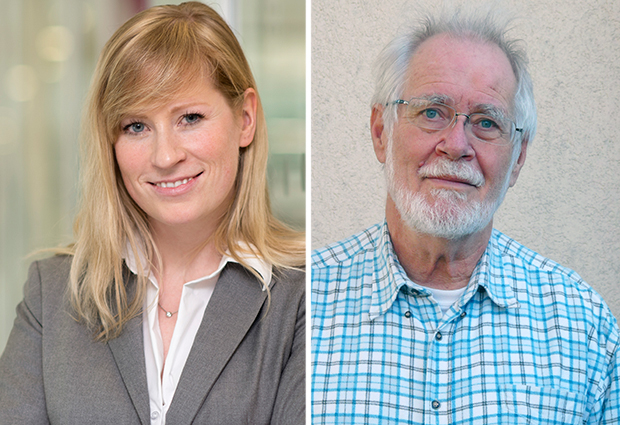

As a child, alumnus Jacques Dubochet was scared of the dark. One day, nervously watching the sun disappearing over the horizon, he headed to his local library determined to find out where it went.

“For me it was necessary to confront my fears with understanding,” explains Dubochet, winner of the inaugural Lennart Philipson award. Taking comfort in knowledge instinctively led him to a career in science, where his defining work came not from studying disappearing light, but disappearing water, developing a technique that revolutionised structural biology.

Friend not foe

“Unfortunately water evaporates in an electron microscope, but when treated with suitable care, water is the electron microscopist’s best friend,” says Dubochet, who together with colleague Alasdair McDowall and Marc Adrian, invented cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) sample preparation. The method enabled samples to be kept in their native state without the need for dyes or fixatives: its development over time has enabled researchers to zoom in on structures, viruses and protein complexes at unprecedented resolution. “Electrons are great: even a single molecule may leave a trace in their beam and electron microscopists have learned to make use of them with breathtaking effect,” he explains. “But they are also rather destructive: the column of an electron microscope must be under a vacuum, while risks of structural damage lurk around every corner.”

For me it was necessary to confront my fears with understanding.

Scientists, including Dubochet had already tinkered with a variety of methods to try and fix biological samples for observations in the electron microscope, but working as a group leader at EMBL Heidelberg in the early 1980s, Dubochet recognised that in order to preserve the natural structure of biological samples for measurement under the electron microscope, they had to remain in their natural environment – water. But to avoid evaporation in the vacuum of the electron microscope column water needs to be frozen, with ice crystals causing further hazards to delicate samples. So Dubochet set out to find a way of freezing water without producing any ice crystals.

Visionary

“Jacques had a vision,” explains Gareth Griffiths, incumbent Chair of EMBL’s Alumni Association, as well as a friend and colleague. “He found a way of freezing thin films of water so fast that crystals had no time to form. At first the idea of “vitrification” of liquid ice was dismissed, but overtime the technique has become increasingly important to life science research, and it is clear today it is Nobel Prize-worthy.” While other structural biology methods require extensive, complicated and potentially disruptive sample preparation techniques, cryo-electron microscopy enables the scientist to view the sample in its natural environment. It is central to the work of labs the world over, including several at EMBL, while cryoEM of vitreous sections (CEMOVIS), is widely regarded as having potential to become a powerful method in the future. “With a bit of chance it’s going to be trivial to see the atomic structure of protein complexes!” Dubochet says excitedly.

After leaving EMBL, Dubochet took up a professorship at the University of Lausanne, fulfilling a passion for teaching, while also introducing courses on ethics and philosophy- an area he is still very active in. “With knowledge comes great responsibility,” he says. Now retired, he looks back with a smile at all he has achieved and experienced. “I have been lucky,” he adds. “Although ‘serendipity’ probably captures it better, being in the right place at the right time. EMBL was the best time of my life: my children were born, I had my best scientific moments and still have plenty of friends here. We often come back to visit, it’s a great pleasure. Voila!”

By Julia Franke

High risk, high gain

Melina Schuh’s approach to science has been described as “fearless”. But dig beneath this steely description of this year’s John Kendrew Award winner and you find a story of outstanding research, fast-track career progression, and innovative outreach.

“In both my diploma and PhD, I tried something high-risk, high-gain and it paid off,” explains Schuh, an alumna whose group has made several important findings in the field of fertilisable eggs in mammals. “Understanding more about oocyte maturation could have important implications for human health, as errors during this process can lead to problems such as miscarriages, birth defects, and infertility.”

In both my diploma and PhD, I tried something high-risk, high-gain and it paid off.

While carrying out her PhD in the Ellenberg group at EMBL Heidelberg, Schuh immediately hit the ground running, and using confocal microscopy established new ways of directly imaging meiosis in mammalian cells. “This was an ambitious project because these cells are very sensitive and meiosis in oocytes is a very long process – but the collaborative working environment at EMBL was hugely motivating,” she says.

After receiving her doctorate, Schuh achieved something rarely heard of in today’s academic world: she was offered a group leader position at the Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB), despite having no formal postdoctoral training. “What distinguished Melina was her independence so early in her career,” says Jan Ellenberg, proudly reflecting on the achievements of his mentee. “From the start, Melina showed courageous and strategic decision making, and in many respects her PhD was like a postdoctoral training.”

Far beyond the bench

Her stunning images of polar body extrusion have graced the covers of several top journals, but Schuh has also been involved in projects that go far beyond the bench. One example is an acclaimed collaboration with artist Rob Kesseler as part of a travelling exhibition that aimed to explore mitosis, called Lens on Life. “There are many shades of research, and through this project we were able to devise creative and inspiring ways of explaining how this fundamental life process is applicable in everyone’s lives,” she says. “Artists and scientists have a lot to learn from one another.”

At the beginning of next year, Schuh will move on to the next stage of an already remarkable career, as a director at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, where ambitious projects in science and beyond will remain at the heart of her work.

“It is important to go for projects you are enthusiastic about,” she adds. “Recently, we led the first study of meiosis in live human oocytes, which has opened up a new and exciting field of research. By continuing to do fundamental biological research on the human system, we hope to contribute to the understanding of this fascinating field, and ultimately also to healthcare and society.”