Understanding developmental plasticity in time and space

A two-week practical course introduced participants to the intricacies of studying the dynamic interplay between organisms and their changing environment, and how this interaction impacts development and evolution.

From soil bacteria to flatworms to humans – living systems have a remarkable ability to adapt and change in response to their environments. This process, called plasticity, plays a crucial role in organisms’ development and survival, as well as in the evolution of species.

Between 24 Jul and 4 Aug 2023, EMBL Heidelberg hosted the EMBO practical course ‘Plasticity in developing systems: time, space, and environment’. The two-week-long course introduced participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to the rapidly growing field of developmental plasticity. Through a series of lectures and practical exercises, the participants learned about the fundamental questions and challenges involved in studying how the myriad of interactions between organisms and their environment impact developmental and evolutionary processes.

Organism-environment interactions and development

“Plasticity, particularly in developing systems, helps us understand how organisms adapt and evolve in response to their environment,” said Aissam Ikmi, Group Leader at EMBL and one of the organisers of the course. “Essentially, plasticity allows living systems to cope with environmental changes through changes in development, life history, physiology, and/or behaviour, making it critical for both immediate survival and long-term evolutionary strategies.”

One of the unique aspects of the course was a series of keynote lectures from stalwarts in the field of developmental biology, with each lecture introducing a different topic in the course. For example, Scott Gilbert, Howard A. Schneiderman Professor of Biology, emeritus, at Swarthmore College, USA, and the author of one of the most influential textbooks in developmental biology, introduced participants to the ‘holobiont’ – the concept that a multicellular organism is a consortium of many species working in concert.

Other keynote speakers included Manu Prakash from Stanford University, Susana Coelho from the Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen, Alexander Jones from the University of Cambridge, Antónia Monteiro from the National University of Singapore, Jonathan Rodenfels from Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, and Kristin Tessmar from the Max Perutz Labs Vienna, Austria. The speakers covered a range of exciting topics, from the energetic costs of early development to plasticity in butterfly wing patterns, to the life cycle of brown algae, and much more.

Hands-on training in developmental plasticity

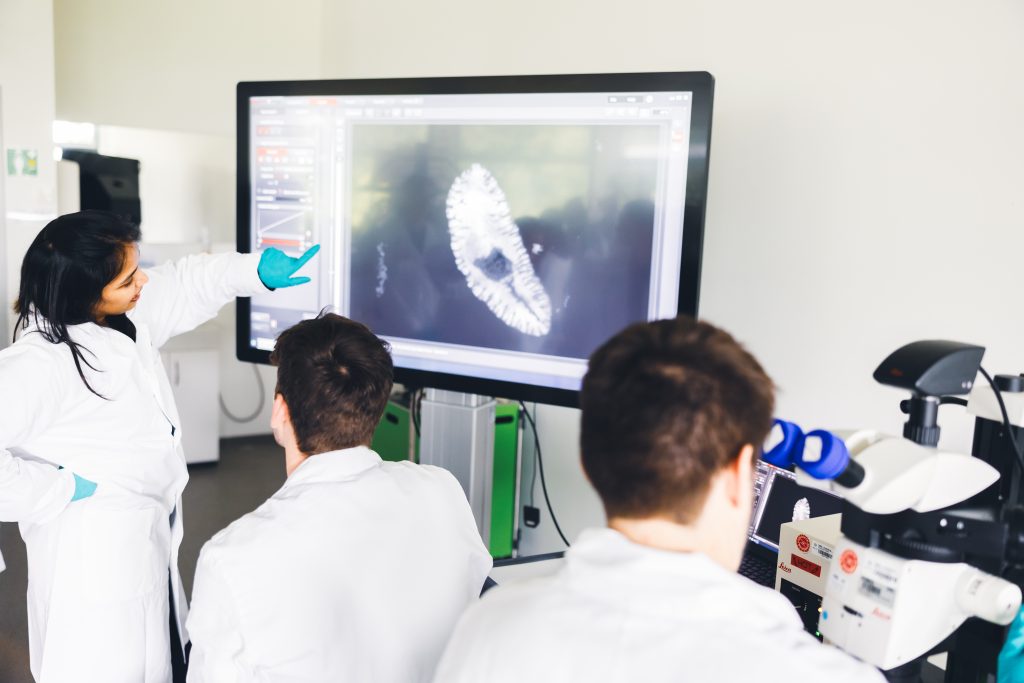

“The Developmental Biology (DB) Unit at EMBL has a strong tradition of using in vivo systems, state-of-the-art imaging and quantitative approaches to study the principles underlying development,” said Alexander Aulehla, Head of the DB Unit and one of the organisers of the course. The organising team harnessed this expertise and collective knowledge to design and develop the workshop, which covers the breadth of topics involved in studying plasticity in developing systems.

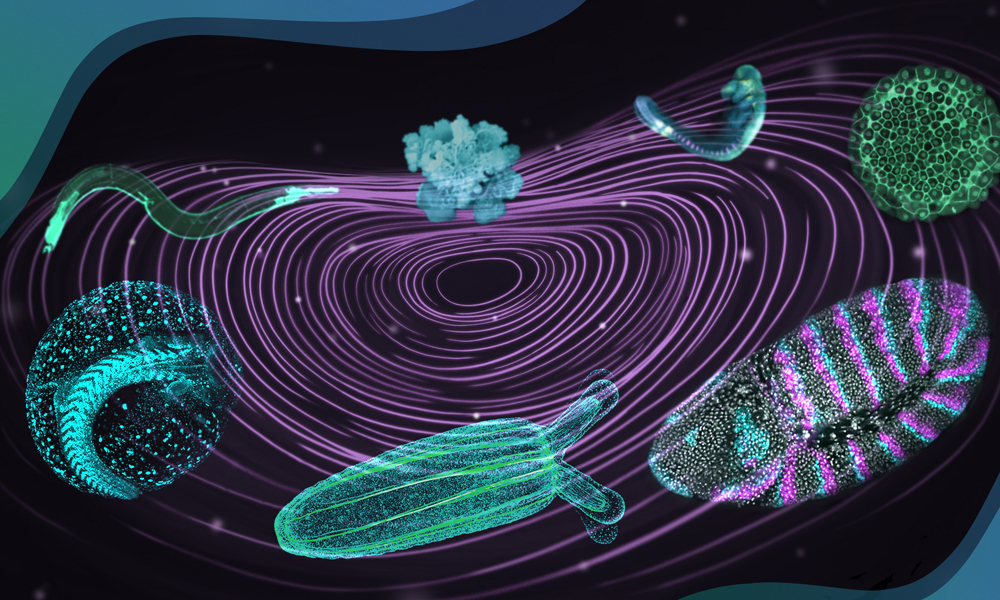

Several of the labs in the unit organised hands-on practicals for the course, during each of which, participants had the opportunity to carry out experiments and analysis using pipelines routinely used in the labs. Some of these practical exercises included studying collective behaviours of soil bacteria (led by the van Gestel Group), imaging developmental processes in 4D (led by the Prevedel and Zimmermann teams), and investigating the phenotypic plasticity of Planarian flatworms (led by the Vu Group). Others involved studying diatom symbiosis in environmental samples (Vincent Group), synthetic biology in a fruit fly model (Crocker Group), biophysical properties of Zebrafish embryonic tissues (Petridou Group), morphogenesis of brain pioneer cells in C. elegans (Rapti Group), and metabolic control of developmental timing (Aulehla and Ikmi groups). In addition, the group of Thomas Greb, researcher at the Centre for Organismal Studies, University of Heidelberg, organised a practical session on plant development and physiology.

“The course was aimed at early career scientists with a STEM background who had developed an interest in developmental biology,” said Alessandra Reversi, DB Unit Research Coordinator and another organiser of the course. “Participants were selected on the basis of the relevance of their research interests, as well as on how the expertise gained during the course could enable them to pursue new research directions. What emerged was a group of participants from a variety of backgrounds and experiences, who were highly motivated and engaged throughout the course.”

In addition to lectures and practicals, a number of networking events during the course allowed participants to interact with each other as well as the speakers, share their research, and brainstorm on science culture and career development.

“Attending ‘Plasticity in developing systems’ was a fantastic experience as an early career researcher (ECR),” said Jennifer Love, a PhD student at the University of Manchester and one of the course participants. “We took part in hands-on practical sessions exploring the relationship between environment and development in a range of organisms, attended inspired curiosity-driven research lectures and had the opportunity to meet and work alongside incredible young scientists. This is the future of Developmental Biology!”

Maria Akhmanova, a course participant from the University of California, Los Angeles, USA, agreed. “This course is a one-of-a-kind experience that ignites a passion for observing and appreciating life, while also delving deep into the biology of a dozen fascinating organisms and how they adapt to the changing environment,” she said.

Looking ahead

“As one of the organizers, the most rewarding aspect was seeing the engagement of the participants and their growth over the course of the workshop,” said Aulehla. “It was deeply satisfying to see young scientists get hands-on experience and gain insights that could shape their future research.”

The team hopes to continue offering the course to early-career researchers who can apply the concepts and training to furthering the field. “Studying developmental plasticity allows us to fully understand the intricate mechanisms through which organisms develop in changing environments and how this interplay can increase their fitness, drive evolution and shape ecosystems,” said Nicoletta Petridou, Group Leader at EMBL and an organiser of the course.

“Our focus has always been to create an environment where learning is dynamic and interactive, and I believe we succeeded in that aspect,” concluded Ikmi.