From the biochemistry of thoughts to the complexity of protein networks

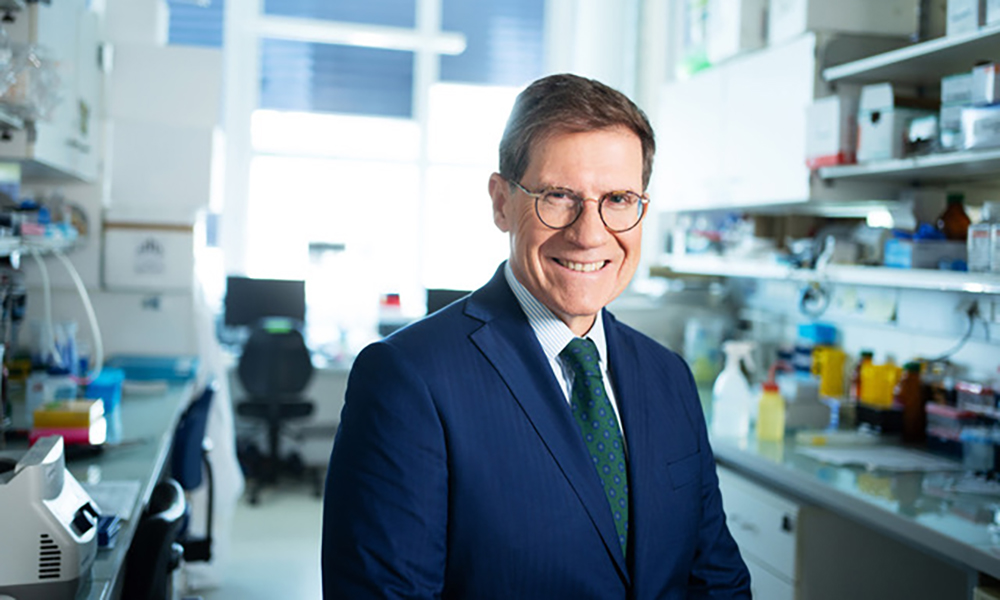

Lennart Philipson Award recipient Giulio Superti-Furga discusses the scientific achievements he's most proud of, the importance of entrepreneurship, and why he had his personal genome sequenced

Giulio Superti-Furga joined EMBL as a postdoc in the early 1990s and stayed for 14 years, becoming a successful group leader in the Developmental Biology Unit and founding the first of many start-ups. His illustrious career has spanned academic research, industry, and beyond, and he chaired the EMBL Alumni Association for eight years (2008-2015). He is currently the Scientific Director and Research Group Leader at the Research Centre for Molecular Medicine (CeMM) in Vienna, which he has led since its founding in 2005, as well as Professor of Medical Systems Biology at the Medical University of Vienna and Scientific Director of Ri.MED Foundation Palermo.

In recognition of his impact as a researcher as well as his far-reaching contributions through training, mentorship, innovation, and entrepreneurship, Superti-Furga was awarded the 2024 Lennart Philipson Award. We recently caught up with him about his early inspirations, what drove him to pursue sci-entrepreneurship, which scientific achievements he’s most proud of, and what led him to have his personal genome sequenced.

When did you first decide that you wanted to be a scientist?

During my late teenage years in Milan, my brother and I developed the conviction that the most interesting question in life is the biochemical basis for thoughts. All other quests and professions appeared mundane and trivial in comparison. I was very idealistic and stuck to the idea of becoming a researcher, while my brother went on to become a doctor. I have never regretted my decision and feel lucky and privileged to have had the emotional, social, and financial possibility of pursuing molecular biology.

What are some of your research achievements that you are most proud of?

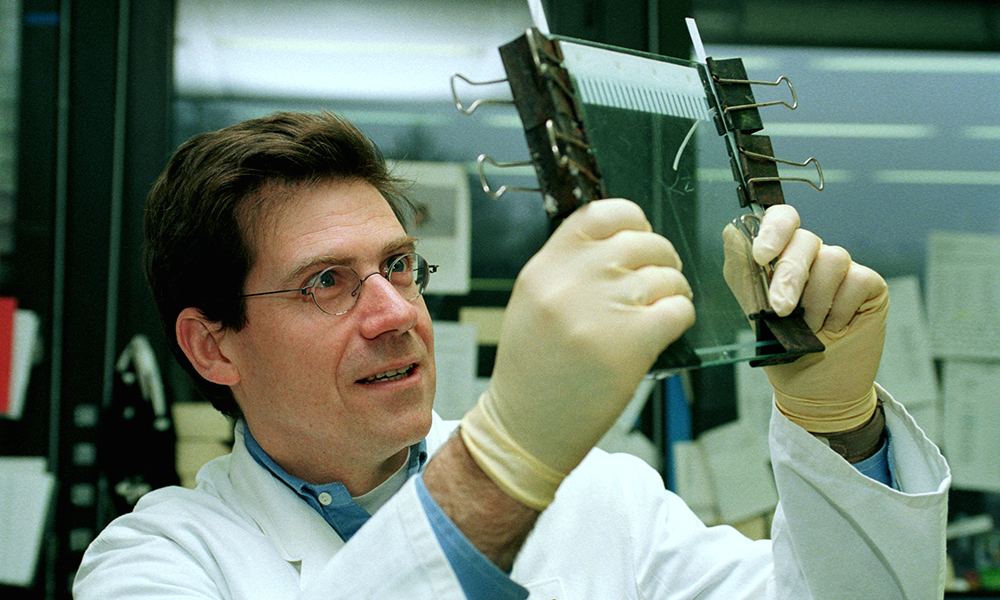

Together with Anne-Claude Gavin, Gitte Neubauer, and a large team of crazily committed scientists at Cellzome and EMBL, we mapped the protein interactions of all yeast gene products in the early 2000s. We knew then that we were being offered unique first insights into the entire molecular machinery of a eukaryotic cell. I am proud of having pushed the idea and coordinated the effort successfully against the backdrop of a sceptical business and scientific environment and many technical odds.

While many people thought this might be dull, repetitive work, the complete picture this created helped us understand some fundamental organising principles of the proteome of eukaryotic cells. It was mind-blowing. I remember a moment, talking with Jörg Schultz about how to analyse the data, when we figured out that we could shift our thinking to a higher level of organisation, considering protein complexes as nodes and shared components as edges. This resulted in an iconic cover of the journal Nature.

A few years later, locked up in the Gellert Hotel in Budapest after the big FEBS meeting, I had a similar experience with Anne-Claude Gavin, Patrick Aloy and Rob Russel. We worked non-stop until we felt we had understood how best to describe quantitatively and statistically the composition of eukaryotic protein complexes. It was exhilarating and unforgettable.

You have co-founded several biotech companies during your career. What are some things researchers entering the sci-entrepreneurship space should know?

Of all the things a researcher can do, founding a company is one of the most creative. It’s not just an idea or a business proposition, it’s a whole little world that you create. This world includes a physical space, a corporate and cultural identity, and a committed community of people. What researchers entering this kind of space should consider is that making a company is similar to having a child. It grows, it has a personality of its own, and it is utterly dependent on you until it becomes fiercely independent, but the responsibility and the feeling of belonging never ceases. It’s a long-term commitment. It’s just incredible to look at everything that’s then enabled by that act of creation. All the jobs, the activities, the collaborations, the families supported, the joys and sorrows, the projects, the drugs – none of which would exist without the company you create.

Can you share some key insights you would like to share with early career researchers?

Here’s what I’d suggest, in a nutshell:

Don’t be afraid: Fear is never a good advisor. Embrace with joy what you want to do and if you fear someone, e.g. a competitor, call them and turn them into an ally.

Be kind: Kindness creates a safe space based on support and trust. Let others be mean, jealous, suspicious. The best people will gather around you if you are fearless and kind.

Work on something important you really care about: You also need to be smart and know how to choose projects you can tackle and where bigger labs don’t blow you out of the water. But if you are diligent and rigorous, you can compete with goliaths that are too large to be nimble and too distracted to be focused.

Communicate: The more information you share, the more information will flow back to you, multiplied. Life is too short and the problems are too big to be secretive. Make everyone around you think along with and cheer for you, and be generous in acknowledging that you profit from the community.

You have been heavily involved in the Global Network of Personal Genome Projects and you are one of the first people to make your own personal genome publicly available. Can you tell us about why this is important?

I have lived mostly in countries where the word ‘gene’ has a bad connotation and people are afraid of everything related to genes and genomes. This comes from the fear of eugenics, of genetically modified organisms, and of things that people do not understand and therefore distrust. About a decade ago, I naïvely thought that everybody in Europe would know their genome by the year 2022. I felt that nothing is as cost-effective and scientifically robust as the medical advantages of full genomic information. But then, society was not ready.

I thought that I can’t preach genomic medicine without the credibility of setting an example. I was the first person to have his personal genome sequenced and published in a non-anonymous way. I had discussed the matter with my two children beforehand, and they were fine with the idea.

Genetic discrimination is, as it should be, anti-constitutional. But the truth is that people do not need genetics to discriminate, they do it all the time based on your face, the colour of your skin, your gender, your name, your social class, your degree of education. Genomic information is too complex still for most people to digest. So, my genome was sequenced for coherence to my educational mandate and as an example for those who discriminate – to show we all come out of Africa and we are all mixtures of populations.

What, in your opinion, is the value of fundamental research, especially in today’s changing global scenario?

Good basic research is the essential positive activity that is at the centre of humankind and its understanding of the world. I love research that creates a change in our collective knowledge and awareness. It’s one of the most noble activities we can do – both a luxury and a fundamental right. We need the moral standing and the ethical roots required to do the right thing, but the main basis for improving the relationship between humans and the planet comes from research. Even our animalesque anthropocentrism can be demasked and corrected once we understand better the neural and social determinants. Research has perhaps never been so important as now, when we are reaching the limits of our planetarian arrogance.

What does EMBL mean to you personally and professionally?

This requires a book! I have always felt well in the communities I lived in, but never quite as well as in the EMBL community. It’s really the only scientific community I know where no nationality dominates and where science is always at the centre of the mission. EMBL feels like home.

During my 14 years at EMBL, I matured from a postdoc to a leader. I arrived single and left with a partner and two children. I had a small but fearless lab and co-founded a start-up that became very large and successful. To this day, I am very close to dozens, perhaps hundreds of EMBLers. I remember the differing but effective styles of former Directors General Lennart Philipson and Fotis Kafatos. I loved so many people, from the washing personnel on the 6th floor to the night guardian, from the Photolab to the legendary cafeteria, from Mary Holmes in the library to the prematurely missed Matti Saraste.

I am forever grateful to EMBL, its founders, its supporters, its community. I have fond memories – of Max Bill’s logo, the beech trees of the Heidelberg campus, the oak trees of the EBI, the cactuses of Monterotondo, and the palm trees of the CRG.

As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, do you have any birthday wishes for EMBL?

I wish that the spirit of EMBL, the ‘what is life’ impetus of the physicists who shifted their attention to the wonders of biology, remains forever enshrined in the institution and is respected if not worshipped by generations of scientists to come. May research be at the heart of the European mission and may EMBL be its multi-site headquarters.