Spindle architecture constrains karyotype evolution

Nature Cell Biology 8 August 2024

10.1038/s41556-024-01485-w

EMBL-Stanford Life Science Alliance fellow Jana Helsen shares how she balanced her life between two laboratories and countries, her latest research paper, and her passion for cover art.

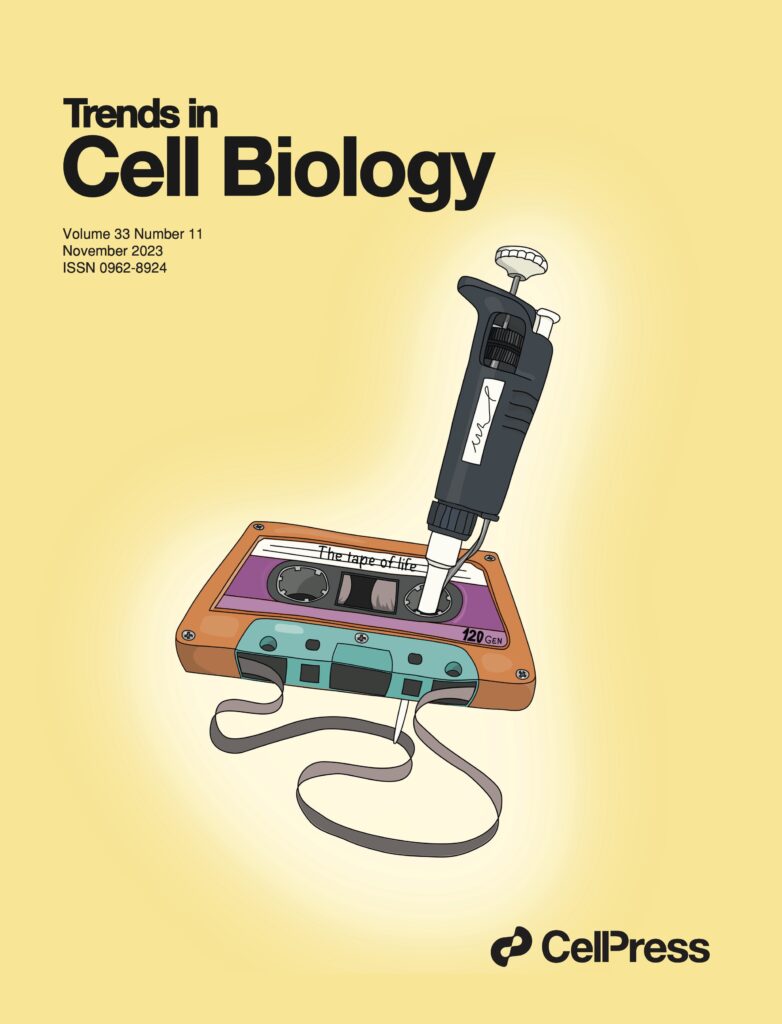

A cassette tape rewound by a pipette – a piece of equipment commonly used in laboratories to measure and transfer tiny amounts of liquid – is not an image you would often see. But this is exactly what greets you as you enter Jana Helsen’s office. And she drew it.

That’s not the only interesting aspect of Helsen’s current life as a scientist. She is also uniquely a joint postdoctoral researcher, moving between the Dey Group at EMBL Heidelberg and the Sherlock lab at Stanford University, USA. This arrangement was made possible through the Bridging Excellence Fellowship Programme of the EMBL–Stanford Life Science Alliance. Helsen was one of the first to receive this type of postdoctoral experience with her supervisors Gautam Dey and Gavin Sherlock.

Recently, she shared her thoughts on this experience that is ending soon, her latest research achievements, and the origin of her hobby that combines passions for both art and science.

In the Dey Lab, we study the evolutionary origins of the nucleus – the cell compartment where DNA is stored, particularly during cell division, the process in which a mother cell gives birth to two identical daughter cells. To tackle this question, we use many different organisms, and my colleagues and I study a wide variety of topics that focus on different aspects of this cellular process. I personally study the evolutionary interaction between chromosomes – the packaged form in which DNA is stored – and the cell division machinery.

In my latest paper, now published in Nature Cell Biology, I investigated whether the cell division machinery can segregate any number of chromosomes. Chromosome numbers can vary dramatically between species, even on very short evolutionary time scales, yet the cell must still manage to duplicate and segregate each chromosome accurately during cell division. Failure to do so results in aneuploidy – an incorrect number of chromosomes – which can result in birth defects and cancers.

We showed that there is a minimum chromosome number a budding yeast cell (my model organism of choice) must have before it starts experiencing a growth delay. If a cell has fewer than five chromosomes, there is a force imbalance in the spindle – the protein machinery responsible for ensuring the proper distribution of chromosomes during cell division. This signals to the cell that it is not yet time to separate its chromosomes, prolonging the time the cell needs to divide.

We also evolved in the lab cells with different chromosome numbers, starting from their original set of 16 chromosomes all the way down to three. We observed that cells with a chromosome number below the tolerability threshold can resolve cell division delay and restore fitness by increasing their number of chromosomes beyond this lower limit.

In addition, I’m also wrapping up an exciting piece of work on the evolution of the centromere – the part of the chromosome where the spindle attaches – which we aim to publish as a preprint later this year.

Overall, we believe that our results will be of broad interest to both cell biologists interested in chromosome segregation, and evolutionary biologists interested in chromosome number evolution.

The study itself is important for several reasons. It provides an explicit experimental example of how the mechanics of a core cellular process can constrain evolutionary processes – something impossible to determine simply through comparisons between extant species. Additionally, it highlights the cellular requirements for stable chromosome segregation.

Our work also shows how experimental evolution can be employed in the emerging field of evolutionary cell biology, which seeks to understand how evolutionary processes work.

I explore the relationship between how the cell division machinery is built and how chromosomes evolve over time.

When I read about the call for fellowship applications for a joint postdoc between Gavin’s lab at Stanford and Gautam’s lab at EMBL, I was immediately intrigued. I knew of Gavin’s work and was very eager to work with him. At the same time, I was curious to join Gautam’s lab as it was just starting out. The combination of their knowledge could give me the perfect opportunity to dive into two research fields I’m very excited about: evolution and cell biology.

Merging the expertise of two labs and two leading research institutes allowed me to learn and use a combination of different techniques, which is a powerful way to tackle challenging biological questions.

I really enjoyed the element of adventure in my experience. I had to move my life between two countries multiple times, get to know new people, new places, different cultures, and different ways to do science.

Learning how science is done in different countries expanded my horizons and made me rethink how I do science myself and how I would like to lead my own research group in the future. I will, for sure, try to implement the best of both working methods and philosophies I was exposed to during my time as a Bridging Excellence Fellow.

Moreover, this experience allowed me to build a network of colleagues and friends that will be essential bridges for potential collaborations across the world in the future, and I am very excited to see where they take me.

I started playing around with digital drawings a couple of years ago, just for fun. Most of my drawings either portray a metaphor or are a bit quirky. Usually, I try to combine different ideas to convey a new message (e.g., a cassette tape and a pipette). Coming up with ideas for a cover really forces me to think about the key messages of my papers and how I can visualise them in an abstract, yet artistic way. To me, conceptualising it is actually as much fun as making the actual drawing.

So far, both drawings I submitted have been selected to be featured on a cover, and I’m waiting to hear back about the one I made for our latest article. My favourite so far is titled ‘Rewinding the tape of life in the lab’ which accompanied our opinion piece ‘Experimental evolution for cell biology’. I feel it is a good representation of the approach I like to use in most of my projects. I’m quite happy with how it turned out, and I had a lot of fun trying to come up with the concept. The metaphor ‘replaying life’s tape’ was coined by the late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould and served as inspiration for the drawing. I also thought it funny (and somewhat flattering) that many people thought I would be too young to remember how cassette tapes work.

When deciding whether to stay in academia, I could not see myself living the same life as some of my scientific role models without losing my identity. After discussing this with some of my peers, we concluded that it is okay to break that mould. You can define the way you do science. It’s easy to compare yourself to other scientists and feel like you should be doing all the things they are doing, but try to use your own strengths, interests, and values to come up with your own unique way of doing science.

Nature Cell Biology 8 August 2024

10.1038/s41556-024-01485-w