Branches: What makes humans tick?

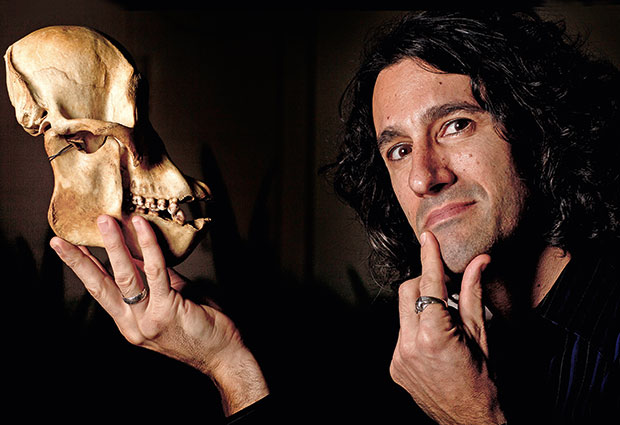

This question fuels Agustín Fuentes’s passion for anthropology, and he shared it with the audience at the Science and Society Symposium What makes us human?

By Julia Roberti

Let’s travel back in time to the origins of human societies, a prominent feature of what we call human nature. How far would we have to go? Would 5000, 50000, 100000 years suffice? Not even close. “When people think of deep time it often conjures up images of the pyramids of ancient Egypt, the Maya civilisation, or prehistoric cave paintings, but to understand what makes us human we need to understand the changes in our lineage starting two million years ago,” explains Agustín Fuentes, a professor of anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. “We are the last hominins standing, sole survivors of a big evolutionary experiment, and we are still evolving biologically, neurologically and behaviourally. It is a complex interplay of biology and environment: this is the baseline and not the end of the story.”

no other species looked into a piece of rock and envisioned a whole different object

Defining human nature is a tricky business. Characteristics that we often associate with people, like caring for others, forming societies and looking after our young, can be observed in many other animals, such as gorillas and blue whales. What has set us apart, then? “The unique ability to coordinate, share intentionality and collaborate creatively became a distinctive pattern in our ancestors that enabled us to do all that we do today,” Fuentes suggests as one answer. “An example is stone tool making. We come up with things that are not logically extractable from our experiences; no other species looked into a piece of rock and envisioned a whole different object within.”

Art of teaching

Fossil evidence indicates that this know-how was passed on through direct teaching as early as 500 000 years ago, and we are the only species that share knowledge this way. “Furthermore, we create things as an expression of human imagination that we call art,” Fuentes explains. “Other animals, such as non-human primates, may experience this as individuals but they do not share, teach or engage in it as we do.”

Good natured

Perhaps even more surprising is the intricate interplay of traits such as competition and collaboration in determining who we are. “Conflict and violence are not opposite, but complementary to cooperation and creativity,” he says.

getting along is in our nature

“By working together, we also developed technologies that transformed our bodies and the environment – this has huge implications for our, and other species’ very survival on the planet. But while war and cruelty make headlines, we often underplay our capacity for compassion – it is amazing that the same parent-to-child hormonal and neuroendocrine responses can be observed in our interactions with strangers and even other species: this is extremely uncommon and a sign that getting along is in our nature.”