Spotlight: Hot waters, shrinking fish

EMBL scientists investigate how zebrafish bodies change when grown at higher temperatures

By Jona Rada

Millions of creatures live in Earth’s oceans, rivers, and other water bodies. Scientists have wondered how such organisms respond to rising temperatures caused by global warming. Mantha Lamprousi, a PhD student in the Dorrity Group at EMBL Heidelberg, is studying what happens to zebrafish, a freshwater species native to Southeast Asia, when they develop into adults at high temperatures.

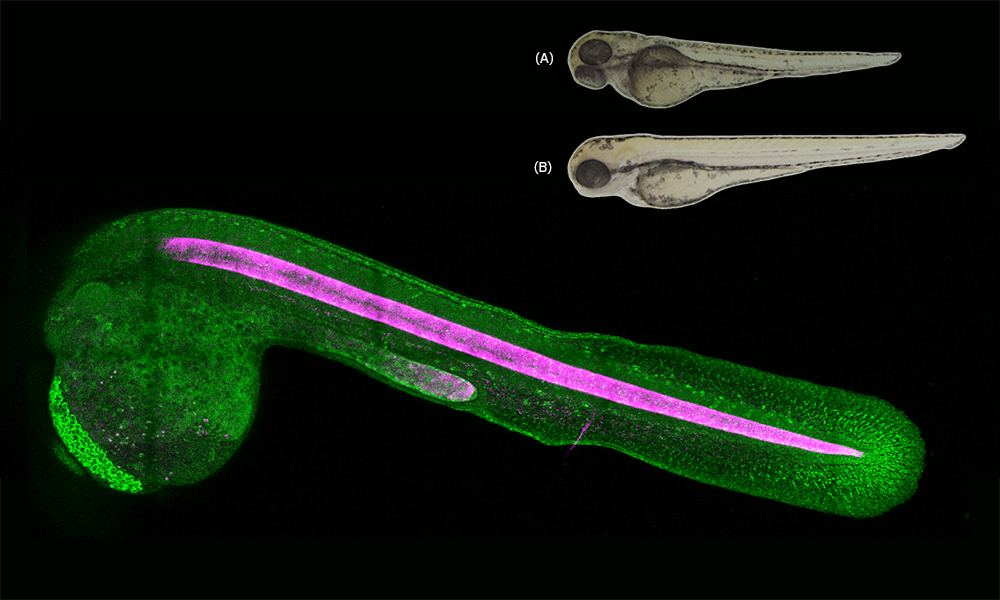

As one can see from the image above, something gets a bit ‘fishy’ when the temperature increases. Zebrafish seem to develop malformed bodies when exposed to temperatures higher than in their natural habitats.

This observation motivated Lamprousi to investigate which cellular processes and cell types in zebrafish are affected by temperature changes. She found out that zebrafish that lack a protein called Hsp47 develop shorter bodies when raised at high temperatures. Hsp47 is a part of a special protein network that helps other proteins acquire their normal state. “It belongs to a class of molecules known as ‘chaperones’,” Lamprousi said, “It helps other proteins fold properly and attain functional forms.”

Hsp47 helps modify the fish’s connective tissue, which plays a crucial role in spine development and function. Temperature increases might tamper with Hsp47, thus changing the interplay between Hsp47 and connective tissue, leading to fish developing shorter bodies.

It remains to be investigated whether reversing the environmental conditions for Hsp47-lacking fish during their development, e.g. by cooling down the water, would reverse the effects on body length as well. For now, Lamprousi is excited about these new molecular findings, which can advance investigations of how changing environmental temperatures will influence life in our waters.