A liquid-like coat mediates chromosome clustering during mitotic exit.

Molecular Cell 16 August 2024

10.1016/j.molcel.2024.07.022

EMBL researchers discovered how a protein switches chromosomes from repelling to attracting each other during cell division

In the human body, several million cells divide every second. This process, called mitosis, is a fundamental biological process during which cells copy, pack, and separate their genetic material (in the form of chromosomes) into daughter cells with the help of specific proteins. A new study from the Cuylen Group at EMBL Heidelberg sheds light on one of the key molecular pathways involved in this process.

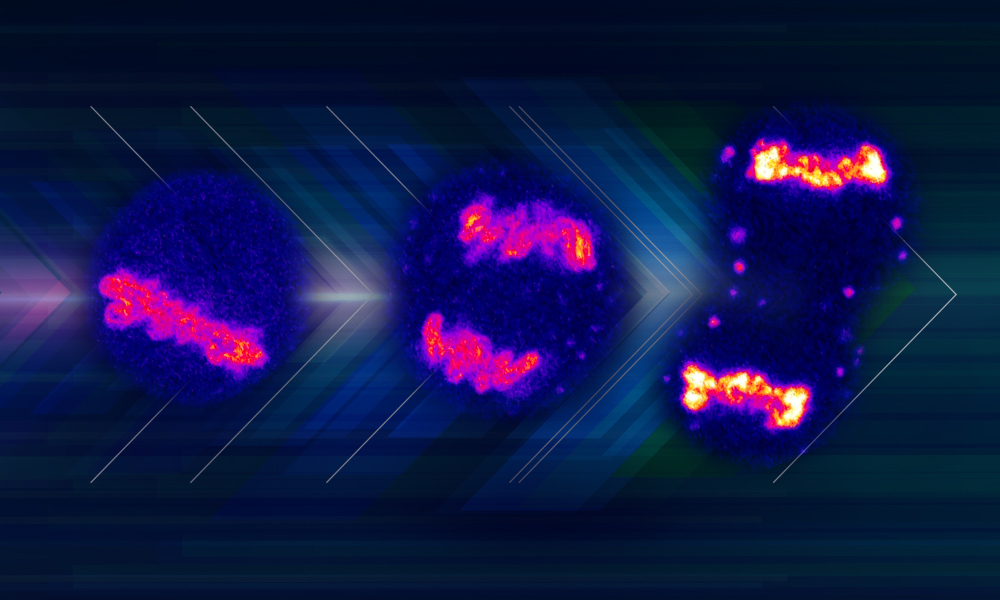

Chromosomes reside in the nucleus for most of the cell’s life. However, when human cells divide, they compact and separate their chromosomes before opening the nucleus and releasing them into the cytoplasm. This facilitates the segregation of chromosomes into daughter cells. However, when the new daughter nuclei form, chromosomes must come together again. How do cells first separate their chromosomes and then bring them back together?

This switching behaviour of chromosomes during mitosis was the basis for Alberto Hernandez-Armendariz’s PhD project in the Cuylen Group at EMBL Heidelberg. The project also involved a collaboration with scientists from the Ellenberg Group at EMBL Heidelberg and the Šaric Group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria.

“We saw that chromosomes repel each other at the beginning of mitosis, and then, in the final stage of the division, they attract each other. We wanted to find out how cells can change the properties of their chromosomes during cell division,” said Hernandez-Armendariz.

The researchers discovered that biophysical properties of chromosomes during mitosis are regulated by a protein called Ki-67, which can switch from acting as a chromosome repellent to a chromosome attractant. “We were surprised to discover that the same protein can have opposite functions and can rapidly switch between them through a chemical modification of the Ki-67 molecule, known as dephosphorylation,” said Cuylen-Häring.

They also found that during the switch, Ki-67 teams up with RNA molecules, forming a liquid-like ‘glue’ on the surface of chromosomes via a process called phase separation. This liquid ‘glue’ sticks chromosomes to each other and helps them to cluster more easily. This, in turn, helps in the formation of daughter nuclei, which contributes to a successful cell division.

“Ki-67 has been used as a cell division marker and cancer prognosis for decades, but we are just now understanding how it contributes to cell division,” said Cuylen-Häring. “I am convinced there is still much more to discover about this intriguing protein.”

Molecular Cell 16 August 2024

10.1016/j.molcel.2024.07.022