Protecting us from our cells

A molecule called insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) boosts the body’s natural defence auto-immune diseases such as type-1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis, scientists at EMBL Monterotondo have found. The findings are especially exciting because IGF-1 is already approved for use in patients, which could speed up the move to clinical trials for treating auto-immune diseases.

Our immune system defends us from harmful bacteria and viruses, but, if left unchecked, the cells that destroy those invaders can turn on the body itself, causing auto-immune diseases like type-1 diabetes or multiple sclerosis. A molecule called insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) boosts the body’s natural defence against this ‘friendly fire’, scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Monterotondo, Italy, have found. The findings, published today in EMBO Molecular Medicine, are especially exciting because IGF-1 is already approved for use in patients, which could speed up the move to clinical trials for treating auto-immune diseases.

“To me what was really striking was the survival rate for multiple sclerosis,” says Daniel Bilbao, who conducted the research with Nadia Rosenthal’s lab at EMBL, “we went from less than 50% survival in untreated animals to over 80% survival in animals that received IGF-1.”

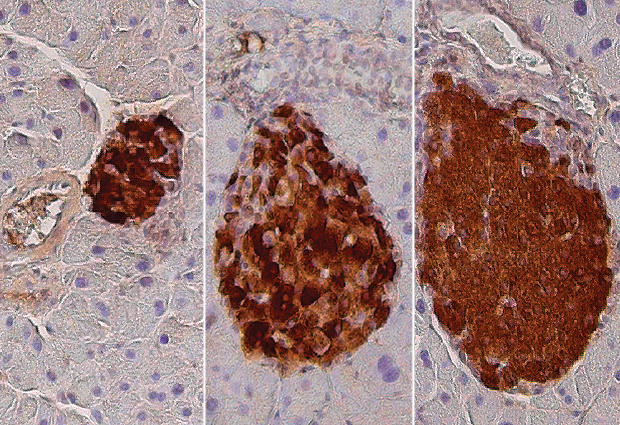

In patients with auto-immune diseases, a group of cells called pro-inflammatory T-effector cells become sensitized to specific cells in the body, identifying them as foreign and attacking them as if they were invading bacteria. If this misdirected attack targets the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, the result is diabetes; if it affects myelin-sheathed cells in the central nervous system, the person suffers from multiple sclerosis. These attacks on the body’s own cells go unchecked due to the failing of another type of immune cell: T-regulatory (T-reg) cells, which, as their name implies, control T-effector cells, shutting them down when they are not needed.

My hope and goal is to now see this applied to humans

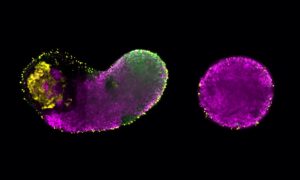

Working with then PhD student Luisa Luciani, Bilbao and Rosenthal found that, if mice with conditions that mimic type-1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis received IGF-1, they started producing more T-reg cells where they were needed – the pancreas and the central nervous system, respectively – and the disease was suppressed. The scientists went on to test IGF-1’s effects on T-reg cells taken from both mice and humans, confirming that IGF-1 acts directly on T-reg cells – rather than indirectly by affecting some other factor that induces T-reg cells to multiply.

In a separate study published earlier this year, Bilbao and Rosenthal had found that IGF-1 has the same effect on another condition in which the immune system goes awry. They found that allergic contact dermatitis, an inflammatory skin disease thought to affect as many as one in five Europeans, is also suppressed in mice by treating them with IGF-1.

“These studies have real clinical significance, because IGF-1 is already an approved therapeutic, which has been tested in many different settings, so it will be much easier to start clinical trials for IGF-1 in auto-immune and inflammatory diseases than it would if we were proposing a new, untested drug,’ says Nadia Rosenthal, former Head of EMBL Monterotondo, and currently at Imperial College London, UK, and Monash University, Australia, where she is Scientific Head of EMBL Australia.

“My hope and goal is to now see this applied to humans, but – as with everything – that will depend on funding,” Bilbao adds.

Rosenthal is planning to further explore the role of IGF-1 in inflammation and regeneration, and its potential for treating conditions such as muscular atrophy, fibrosis or heart disease.