What makes us human? Or not…

Using a human-themed infographic, we take up the debate.

Transposons

Transposons

Make us human…

Sequences that originate from transposons, or ‘jumping genes’, make up approximately 50 per cent of the human genome. However, most scientists consider that most stopped jumping around 50 million years ago and ‘fossilised’, thus making the human genome much more stable than that of other apes. The ones that are still active are kept silent by a variety of repression mechanisms.

Or not…

Transposons are often regarded as ‘DNA parasites’. Viruses and transposons share some features in their genome structures and biochemical abilities, leading to speculation that they share a common ancestor.

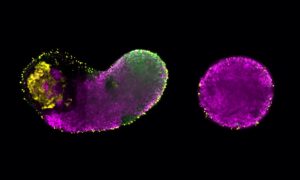

Mitochondria

Mitochondria

Make us human…

Mitochondria arose between 1 and 2 billion years ago and contributed to the emergence of animals, plants and fungi, the so-called eukaryotes. Since then, they have become important components of all eukaryotic cells, including our own. They act as ‘powerhouses’ that use oxygen to generate most cellular energy.

Or not…

Different theories exist on the origin of mitochondria, but they all entail endosymbiosis: many years ago a host cell ‘swallowed’ another cell, probably similar to today’s bacteria. This symbiosis co-evolved, providing both partners with physiological advantages. Mitochondria contain genes that they continue to exchange with the nucleus, constantly reinforcing their collaboration.

Parasites

Parasites

Make us human…

Parasites, like lice or fleas, co-existed and long co-evolved with humans. Recent research indicates that they might have had more influence on us than just provoking bad mood: parasites led to widespread grooming habits in most apes and hominids species, thus reinforcing social links and helping to establish hierarchies.

Or not…

They have several pairs of legs, antennae, and feed from our blood: they are definitely not human! Parasites belong to different species that, although some might have evolved to become more specific to humans, are very far from the human genus in the evolution tree.

Microbiota

Microbiota

Make us human…

Since our last common ancestor with apes, we lost most of our hair, adapted our digestive and nervous systems, and shaped our environment to protect us from pathogens and dangers. All these characteristics distinguish us from our hominid ancestors and make us truly human, even if bacteria are still everywhere within and around us.

Or not…

According to recent studies we host more bacteria then we have human cells. They interact with almost all our main functions and are crucial to maintain our general health, help us digest, shape our immune system and maybe even our brains: we are like a bacteria-scale planet with various ecosystems hosting specific populations in constant interaction with their environment.

Replacement joints

Replacement joints

Make us human…

Our big brain has allowed us to devise ways to shape our environment, but also to enhance our bodies. This is a unique characteristic of humans: replacement joints are a product of our ingenious grey matter and can enable our bodies to function better and longer.

Or not…

Replacement joints are usually made of very resistant ceramic material, sometimes combined with an extremely hard synthetic

Organ transplants

Organ transplants

Make us human…

Currently most organ transplants come from human donors; however, there is a shortage and researchers are looking for new sources. One tantalising prospect would be to grow organs in labs from the patients’own cells.

Or not…

Surgeons are also looking to another potentially plentiful source: animals. Research into how to make animal organs compatible with the human body is currently burgeoning. Cow tendons, for example, can already be implanted to heal diseased knees in some situations.