Forgetting to learn

Scientists discover neural mechanisms in mouse brains that indicate that we actively forget as we learn

They say that once you’ve learned to ride a bicycle, you never forget how to do it. But new research suggests that while learning, the brain is actively trying to forget. The study, by scientists at EMBL and University Pablo Olavide in Sevilla, Spain, is published today in Nature Communications.

“This is the first time that a pathway in the brain has been linked to forgetting, to actively erasing memories,” says Cornelius Gross, who led the work at EMBL.

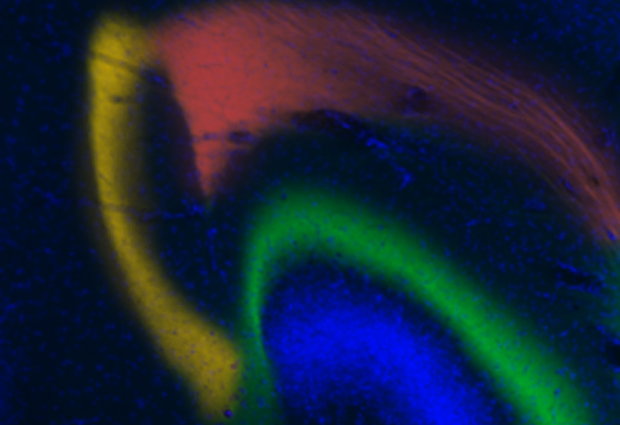

At the simplest level, learning involves making associations, and remembering them. Working with mice, Gross and colleagues studied the hippocampus, a region of the brain that’s long been known to help form memories. Information enters this part of the brain through three different routes. As memories are cemented, connections between neurons along the ‘main’ route become stronger.

When they blocked this main route, the scientists found that the mice were no longer capable of learning a Pavlovian response – associating a sound to a consequence, and anticipating that consequence. But if the mice had learned that association before the scientists stopped information flow in that main route, they could still retrieve that memory. This confirmed that this route is involved in forming memories, but isn’t essential for recalling those memories. The latter probably involves the second route into the hippocampus, the scientists surmise.

But blocking that main route had an unexpected consequence: the connections along it were weakened, meaning the memory was being erased.

“Simply blocking this pathway shouldn’t have an effect on its strength,” says Agnès Gruart from University Pablo Olavide. “When we investigated further, we discovered that activity in one of the other pathways was driving this weakening.”

Interestingly, this active push for forgetting only happens in learning situations. When the scientists blocked the main route into the hippocampus under other circumstances, the strength of its connections remained unaltered.

“One explanation for this is that there is limited space in the brain, so when you’re learning, you have to weaken some connections to make room for others,” says Gross. “To learn new things, you have to forget things you’ve learned before.”

The findings were made using genetically engineered mice, but with help from Maja Köhn’s lab at EMBL the scientists demonstrated that it is possible to produce a drug that activates this ‘forgetting’ route in the brain without the need for genetic engineering. This approach, they say, might be interesting to explore if one were looking for ways to help people forget traumatic experiences.

Imparare dimenticando

Una nuova ricerca sui meccanismi neurali nei topi suggerisce che mentre si impara, si dimentica ciò che si è già appreso

Si dice che una volta imparato ad andare in bicicletta, non si scorda mai. Ma una nuova ricerca suggerisce che mentre impariamo, il nostro cervello cerca di dimenticare ciò che abbiamo appreso in precedenza. Lo studio, condotto dai ricercatori dell’EMBL e dell’Università Pablo Olavide di Siviglia, in Spagna, è pubblicato oggi su Nature Communications.

“Questa è la prima volta che un meccanismo neurale viene associato all’atto di dimenticare, ovvero cancellare attivamente le memorie esistenti,” dice Cornelius Gross, il ricercatore dell’EMBL che ha guidato lo studio.

Al livello più semplice, imparare significa creare associazioni mentali, e ricordarle. Nei topi, Gross e colleghi hanno studiato l’ippocampo, una regione del cervello responsabile della formazione di memorie. Informazioni provenienti dall’esterno entrano in questa regione del cervello attraverso tre vie differenti. Man mano che si formano nuove memorie, le connessioni tra i neuroni lungo la via ‘principale’ diventano più forti.

I ricercatori hanno scoperto che, quando questa via è bloccata, i topi non sono più in grado di imparare un riflesso condizionato – per esempio, associare un suono a una conseguenza, ed anticipare questa conseguenza. Ma se il riflesso condizionato è appreso prima che gli scienziati interrompano il flusso d’informazioni attraverso la via principale, i topi sono in grado di recuperare la memoria creata in precedenza. Questo conferma che la via principale serve a creare memorie, ma non è necessaria per richiamarle alla mente. Da ciò, i ricercatori hanno dedotto che l’atto di ricordare probabilmente coinvolge una via alternativa attraverso cui le informazioni raggiungono l’ippocampo.

Tuttavia, bloccare la via principale ha una conseguenza inaspettata: le connessioni tra i neuroni lungo questa via si indeboliscono, e le memorie sono cancellate.

“Bloccare questo percorso neurale non dovrebbe avere nessun effetto sulla forza delle connessioni tra i neuroni,” spiega Agnès Gruart, Professoressa all’Università Pablo Olavide. “Studiando questo processo nei dettagli, abbiamo scoperto che responsabile di questo indebolimento è una delle altre vie che conducono le informazioni all’ippocampo.”

Curiosamente, lo stimolo a dimenticare avviene solo in situazioni in cui il cervello cerca di imparare. Se i ricercatori bloccano la via principale in altre condizioni, la forza delle connessioni tra i neuroni rimane inalterata.

“Una spiegazione potrebbe essere che lo spazio nel cervello è limitato, per cui quando impariamo, siamo costretti ad indebolire alcune connessioni per fare spazio ad altre,” dice Gross. “Per imparare cose nuove, bisogna dimenticare quelle imparate in precedenza.”

Queste scoperte sono state rese possibili grazie all’uso di topi geneticamente modificati, ma con l’aiuto del gruppo di Maja Köhn presso l’EMBL, i ricercatori hanno dimostrato come sia possibile produrre una sostanza che attiva il percorso che porta a dimenticare senza ricorrere all’ingegneria genetica. Questo approccio, secondo i ricercatori, potrebbe essere preso in considerazione se si volesse sviluppare una terapia per aiutare le vittime di eventi traumatici a dimenticare tali eventi.