Towards personalised breast cancer treatment

Largest-ever study of breast cancer genomes, led by Wellcome Genome Campus researchers, reveals new genes and mutations involved in the disease

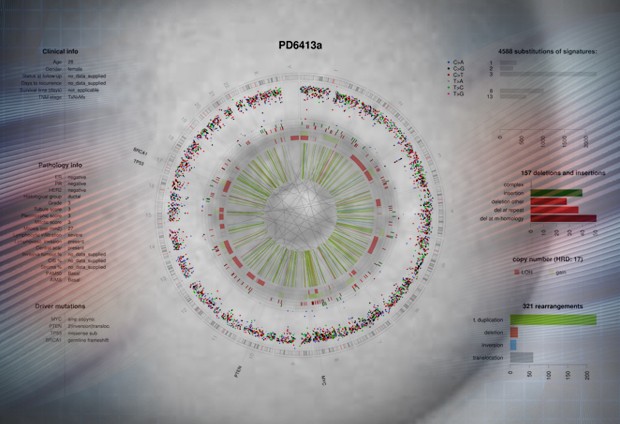

The largest-ever study to sequence the whole genomes of breast cancers has uncovered five new genes associated with the disease and 13 new mutational signatures that influence tumour development. Published in Nature and Nature Communications, two studies from the Wellcome Genome Campus pinpoint where genetic variations in breast cancers occur. The findings provide insights into the causes of breast tumours and demonstrate that breast-cancer genomes are highly individual.

Each patient’s cancer genome provides a complete historical account of the genetic changes that person has acquired throughout life. As they develop from a fertilised egg into full adulthood, a person’s DNA gathers genetic changes along the way. Human DNA is constantly being damaged, either by things in the environment or simply from regular wear and tear in the cell. These mutations form patterns–mutational signatures–that can be detected, and give us clues about the causes of cancer.

Unpicking the genetic variations between cancers is crucial to developing improved therapies.

An international collaboration, led by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute with contributions from EMBL-EBI, analysed 560 breast cancer genomes from cancer patients from the US, Europe and Asia. The team hunted for mutations that encourage cancers to grow and looked for mutational signatures in each patient’s tumour. They found that women who carry mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, who therefore have increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, had whole-cancer genome profiles that were very different to other breast cancers and highly distinctive from one other.

This discovery could be used to classify patients more accurately for treatment.

“In the future, we’d like to be able to profile individual cancer genomes so that we can identify the treatment most likely to be successful for a woman or man diagnosed with breast cancer,” says Nik-Zainal of the Sanger Institute. “It is a step closer to personalised healthcare for cancer.”

Location, location, location

Exactly where mutations occur in breast cancer genomes is important, too. Ewan Birney, Senior Scientist and Director of EMBL-EBI, used new computational techniques to analyse the sequence of genetic information held in each of the sample genomes.

“We know that genetic changes and their position in the cancer genome influence how a person responds to a cancer therapy,” he explains. “For years we have been trying to figure out if parts of DNA that don’t code for anything specific have a role in driving cancer development. This study gave us the first large-scale view of the rest of the genome, uncovering some new reasons why breast cancer arises. It also gave us an unexpected way to characterise the types of mutations that happen in certain breast cancers.”

“Unpicking the genetic variations between cancers is crucial to developing improved therapies,” says Mike Stratton, Director of the Sanger Institute. “This huge study, the largest of any one cancer type to date, gives insights into which genetic variations exist, and where they are in the genome. This has implications for other types of cancer, too. The study itself shows it is possible to sequence individual cancer genomes and this should lead to benefits for patients in the long term.”

Funding

The work for both papers has been funded through the ICGC Breast Cancer Working group by the Breast Cancer Somatic Genetics Study (BASIS), a European research project funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2010-2014) under the grant agreement number 242006; the Triple Negative project funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant reference 077012/Z/05/Z) and the HER2+ project funded by Institut National du Cancer (INCa) in France (Grants N° 226-2009, 02-2011, 41-2012, 144-2008, 06-2012). The ICGC Asian Breast Cancer Project was funded through a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A111218-SC01).

This post was originally published on EMBL-EBI News.