Life in the periphery

Storage of pre-made nuclear pores allows for rapid cell division in fruit fly embryos, EMBL scientists find

Encircling the city of Paris, a dense network of streets flows into the Boulevard Périphérique. Just as portes in the Périphérique regulate traffic and link Paris to its metropolitan region, nuclear pores control traffic between the nucleus and the rest of the cell.

In a study published in Cell, Bernhard Hampoelz and his colleagues from the Beck and Schwab groups at EMBL solved the mystery of how fruit fly embryos rapidly grow without risking damage to their genetic material.

For an embryo to grow from one cell to dozens, its nucleus has to get molecular tools ready for cell division. But the embryo faces an obstacle: it needs pores to ship these tools from the metropolitan area of the cell to inside the nucleus.

In a regular cell, nuclear pores are created by first drilling a hole into the nuclear envelope and then building a pore structure within that hole. But a breached nuclear envelope is not so good for a growing fly embryo, since it could let in matter that leads to DNA damage.

The microscope scans lot of sections of the sample within only a few nanometers’ distance

The process of drilling a hole and building a pore inside it is also slow, taking thirty minutes to an hour. By contrast, the entire cell division cycle of an early fruit fly embryo takes only about six to twelve minutes. Not only does this embryo have a way to rapidly bring in pores, though, but it does so in a way that does not puncture the nuclear envelope. How?

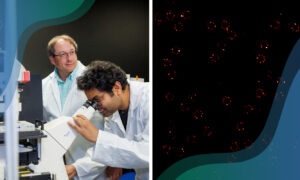

The answer to this mystery, according to Beck, is a huge storage of pre-made pore structures waiting outside the nucleus. The Drosophila embryo comes outfitted with a backpack of protein from its mother, which it uses to build these nuclear pores along membranes in a compartment called Annulate Lamellae (AL). Like cars merging onto the Périphérique, these pores feed into the nuclear envelope. Thanks to FIB-SEM microscopy, an advanced 3D imaging technique brought into the game by Yannick Schwab’s team, the researchers could see that these pores are engulfed by the membranes of the nucleus. “FIB-SEM allows you to look through a large volume of a sample at a very high resolution,” Hampoelz said. “The microscope scans lot of sections of the sample within only a few nanometers’ distance.”

Beck and colleagues found that when ALs are outside the nucleus, they lack the ability to transport the tools the embryo needs for cell division. When ALs feed into the nuclear envelope, however, they mature and can contribute to the growing nucleus. Thanks to these ALs, “the embryo never needs to drill a new hole,” Beck concluded. “It is able to skip this step.”

Further, Hampoelz saw that the less ALs a cell had floating in its cytoplasm, the slower its nucleus grew. “So, there must be regulation involved,” he said. “The general question, ‘How do I integrate this many pores into my nucleus?’ is a fundamental one for a cell.” It is a question that Hampoelz plans to investigate further.