Cell changes drive breast cancer relapse

Researchers identify features of residual breast cancer cells that suggest new approaches for preventing relapse

Relapse is now the main cause of death for breast cancer patients. Researchers at EMBL have found that, in mice, the tumour cells that survive therapy and eventually cause a relapse have specific traits that distinguish them from healthy cells. In a study published today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, the scientists revealed that two of these traits could be promising targets for treatments to reduce tumour recurrence in breast cancer patients.

“Our results suggest that residual cells retain an ‘oncogenic memory’ that could be exploited to develop drugs against breast cancer recurrence,” says Martin Jechlinger, who led the research at EMBL.

Thanks to improvements in primary care, more and more breast cancer patients survive the initial tumour. Although treatments like chemotherapy and mastectomies aim to eliminate all of a patient’s tumour cells, breast cancer cells that survive these initial therapies often reinitiate growth, causing a relapse further down the line. These residual cells are difficult to identify and analyse because, until they relapse, they look and act as normal cells. This means breast cancer relapse has remained largely unexplored, and makes it difficult to predict if and when a patient will experience relapse.

Residual cells have a chemical signature

“We found that residual cells have molecular traits that clearly distinguish them from normal breast tissue, and seem to cause relapse,” Jechlinger explains. “When we treated those features in mice, their tumours were less likely to recur.”

When we treated those features in mice, their tumours were less likely to recur

Jechlinger and colleagues found that, compared to healthy cells, residual cancer cells have altered lipid metabolism. This contributes to maintaining high levels of ‘reactive oxygen species’ — chemically reactive molecules that are known to damage DNA. The scientists think that this damage triggers the relapse.

The team then compared the findings from the mouse model to samples from breast cancer patients, thanks to collaborators at the European Institute of Oncology in Milan, Italy, and the National Centre for Tumour Diseases in Heidelberg, Germany. The two sets of results were consistent, which suggests they could be useful to understand and treat breast cancer recurrence in humans.

“Every patient is different and every story is unique, but our results suggest that lipid metabolism is an exciting therapeutic target to reduce breast cancer recurrence,” says Kristina Havas, who carried out much of the research in Jechlinger’s lab at EMBL.

Jechlinger describes the paper in a video in JCI’s ‘Author’s Take’ series:

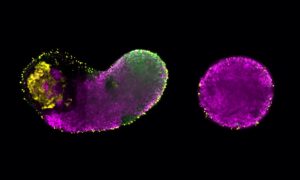

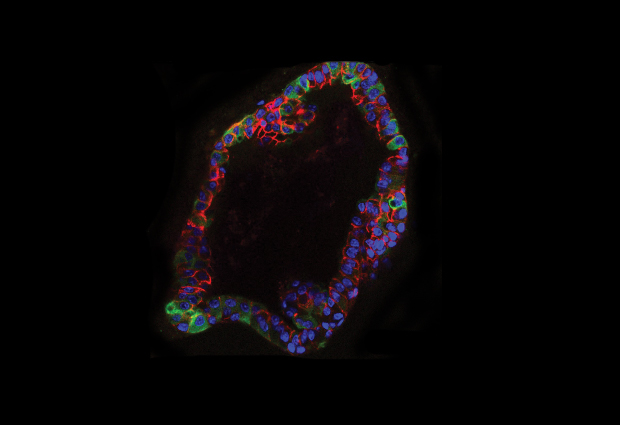

Organotypic structures or ‘organoids’

In this study, to isolate and characterise the cells which survived therapy, the researchers used organotypic structures, or organoids.

Organoids are small clusters of cells cultured outside the body that accurately mimic some of the structure and function of real organs. Organoids can be used for drug testing, investigating personalised therapies and understanding organ development.