A new link between stem cells and tumors

Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg and the Institute of Biomedical Research of the Parc Científic de Barcelona (IRB-PCB) have now added key evidence to claims that some types of cancer originate with defects in stem cells. The study, reported this week in the on-line edition of Nature Genetics (September 4) shows that if key molecules aren’t placed in the right locations within stem cells before they divide, the result can be deadly tumors.

Cells in the very early embryo are interchangeable and undergo rapid division. Soon, however, they begin differentiating into more specific types, finally becoming specialized cells like neurons, blood, or muscle. As they differentiate, they should stop dividing and usually become embedded in particular tissues. Some tumor cells are more like stem cells because they are identical, they divide quickly, and in the worst case – metastasize – they wander through the body and implant themselves in new tissues.

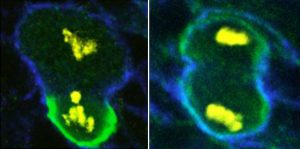

Specialized cells may die through age or injuries, so the body keeps stocks of stem cells on hand to generate replacements. Usually the stem cell divides into two types: one that is just like the parent, which is kept to maintain the stock, and another that differentiates. This is what happens with neuroblasts. Cell division creates one large neuroblast and a smaller cell that can become part of a nerve. This process is controlled by events that happen prior to division. The parent cell becomes asymmetrical: it collects a set of special molecules, including Prospero and other proteins, in the area that will bud off and become the specialized cell.

“This asymmetry provides the new cell with molecules it needs to launch new genetic programs that tell it what to become,” says Cayetano González, whose group began the project at EMBL and has continued the work as they moved to the IRB-PCB. “The current study investigates what happens when the process of localizing these molecules is disturbed.”

Whether Prospero and its partners get to the right place depends on the activity of specific genes in the stem cell. EMBL PhD student Emmanuel Caussinus from González’s group created neuroblasts in which these genes were disrupted. “We no longer had normal neuroblasts and daughter cells capable of becoming part of a nerve,” Caussinus says. “Instead, we had a tumor.”

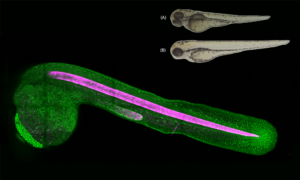

When these altered cells were transplanted into flies, the results were swift and dramatic. The tissue containing the altered cells grew to 100 times its initial size; cells invaded other tissues, and death followed. The growing tumor became “immortal”, Caussinus says; cells could be retransplanted into new hosts for years, generation after generation, with similar effects.

The study proves that specific genes in stem cells – those which control the fates of daughter cells – are crucial. If such genes are disrupted, the new cells may no longer be able to control their reproduction, and this could lead to cancer. “It puts the focus on the events that create asymmetrical collections of molecules inside stem cells,” González says. “This suggests new lines of investigation into the relationship between stem cells and tumors in other model organisms and humans.”