A unique arrangement for egg cell division

A unique arrangement for egg cell division

Which genes are passed on from mother to child is decided very early on during the maturation of the egg cell in the ovary. In a cell division process that is unique to egg cells, half of the chromosomes are eliminated from the egg before it is fertilised. Using a powerful microscope, researchers from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) have now revealed how the molecular machinery functions that is responsible for chromosome reduction of egg cells in mice. In the current issue of Cell they report the assembly of this machinery, which is very different from what happens in all other cells in the body. The process is likely conserved across species and the new insights might help shed light on defects occurring in human egg cell development.

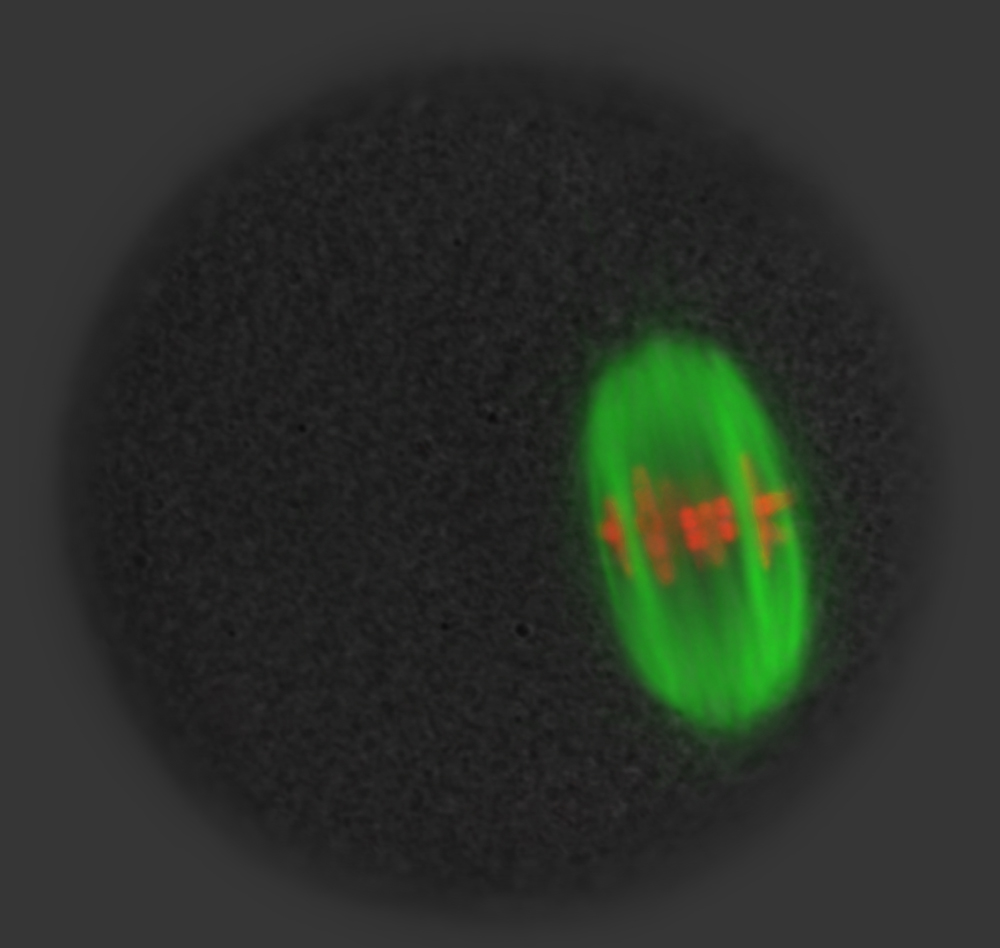

The first step in the development of an egg cell is the division of its progenitor cell, the oocyte. Unlike other cells in the body, an oocyte does not divide equally to produce two identical daughter cells. Instead, it undergoes a reducing division, which halves its genetic material to generate a single egg cell with 23 instead of the normal 46 chromosomes in humans. It is crucial that the egg has half the normal set of chromosomes, because the second half is brought in by the sperm cell during fertilisation. The molecular apparatus that makes sure that the egg ends up with the correct number of chromosomes is a bipolar spindle consisting of protein filaments, called microtubules that are part of the cell’s skeleton. Spindle microtubules attach themselves to the chromosomes, separate them and pull one half out of the oocyte into a small polar body that is later discarded.

“Microtubule spindles are found in all dividing cells. What is special about oocytes is that they lack specialised spindle-forming organelles, called centrosomes,” says Jan Ellenberg, Coordinator of the Gene Expression Unit at EMBL, “all other cells contain two centrosomes from where the microtubules originate. They predetermine the bipolar structure of the spindle that is essential to extrude exactly half of the chromosomes outside of the egg. For a long time we did not understand how mammalian oocytes could assemble a bipolar spindle without such centrosomes.”

Tracking spindle assembly over time with a high resolution microscope in live mouse oocytes, Ellenberg and his PhD student Melina Schuh found that the missing centrosomes are replaced by a flexible system of many small microtubule organising centres (MTOCs) in oocytes. Like centrosomes, these MTOCs serve as platforms from which microtubules grow, but they are not permanent structures. MTOCs only form when the division is about to start and accumulate in the cell’s centre. There, the around 80 individual MTOCs start interacting in a tug-of-war of pulling and pushing each other. This ultimately leads to a self-organised spindle with two poles in which all chromosomes are accurately aligned for the subsequent chromosome elimination.

“Assembling a spindle from so many centres takes very long and involves a lot of coordination in space and time,” says Melina Schuh, who carried out the research in Ellenberg’s lab, “if the spindle fails to accurately segregate the chromosomes, this results in diseases like Down syndrome and infertility. It is therefore very important that we now understand how this crucial division at the beginning of life is orchestrated.”