Deciphering the regulatory code

EMBL scientists take new approach to predict gene expression

Click on image to download a high resolution version (tiff).

Embryonic development is like a well-organised building project, with the embryo’s DNA serving as the blueprint from which all construction details are derived. Cells carry out different functions according to a developmental plan, by expressing, i.e. turning on, different combinations of genes. These patterns of gene expression are controlled by transcription factors: molecules which bind to stretches of DNA called cis-regulatory modules (CRMs), and, once bound, switch the relevant genes on or off. Thanks to scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, it is now possible to accurately predict when and where different CRMs will be active. The study, published today in Nature, is a first step towards forecasting the expression of all genes in a given organism and demonstrates that the genetic regulation that is crucial for correct embryonic development is more flexible than previously thought.

Through an interdisciplinary collaboration between biologist Robert P. Zinzen, computer scientist Charles Girardot and statistician Julien Gagneur, a novel, integrated approach was possible. They combined detailed experimental data about where and when transcription factors are binding to CRMs with a computational approach, and were able to forecast CRM activity.

“Going from global binding data to CRM activity was a big challenge in the field – one which we have now begun to overcome”, says Eileen Furlong, who headed the study.

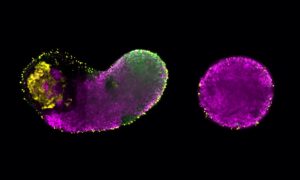

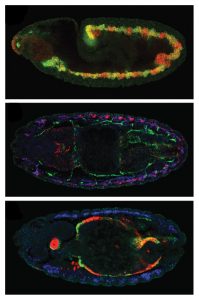

Using a comprehensive, systematic approach, the scientists identified and recorded the binding profiles – i.e. the combinations of transcription factors binding at different times and places – of approximately 8000 CRMs involved in regulating muscle development in the fruit fly Drosophila. The activity of a number of such CRMs had been previously studied, and the EMBL team used this information to group them into classes according to the type of muscle and developmental stages they were active in. The scientists then trained a computer to unravel the binding profiles for each of these groups, and search the 8000 newly identified CRMs for ones whose binding profiles fitted that picture. Such CRMs were predicted to have similar activity patterns, implying they are involved in regulating the development of the same muscle type.

When the scientists tested their predictions experimentally, the results were not only accurate but also enlightening. It turns out that the regulatory code, in which one binding profile leads to one pattern of CRM activity, is actually not that straightforward. CRMs with strikingly different binding profiles can have similar patterns of activity. This plasticity was unexpected, but makes sense in evolutionary terms, the researchers say. The fact that different combinations of transcription factors, or binding codes, can regulate the same developmental process means that even if some transcription factors or CRMs change or are lost during an organism’s evolution, it can still develop a gut muscle, for instance.

“What’s exciting for me is that this study shows that it is possible to predict when and where genes are expressed, which is a crucial first step towards understanding how regulatory networks drive development”, Furlong concludes.