Drought resistance explained

Structural study at EMBL reveals how plants respond to water shortages

Much as adrenaline coursing through our veins drives our body’s reactions to stress, the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) is behind plants’ responses to stressful situations such as drought, but how it does so has been a mystery for years. Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Grenoble, France, and the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas (CSIC) in Valencia, Spain discovered that the key lies in the structure of a protein called PYR1 and how it interacts with the hormone. Their study, published online today in Nature, could open up new approaches to increasing crops’ resistance to water shortage.

Under normal conditions, proteins called PP2Cs inhibit the ABA pathway, but when a plant is subjected to drought, the concentration of ABA in its cells increases. This removes the brake from the pathway, allowing the signal for drought response to be carried through the plant’s cells. This turns specific genes on or off, triggering mechanisms for increasing water uptake and storage, and decreasing water loss. But ABA does not interact directly with PP2Cs, so how does it cause them to be inhibited? Recent studies had indicated that the members of a family of 14 proteins might each act as middle-men, but how those proteins detected ABA and inhibited PP2Cs remained a mystery – until now.

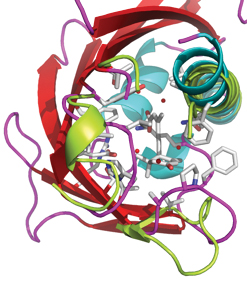

A group of scientists headed by José Antonio Márquez from EMBL Grenoble and Pedro Luis Rodriguez from CSIC looked at one member of this family, a protein called PYR1. When they used X-ray crystallography to determine its 3-dimensional structure, the scientists found that the protein looks like a hand. In the absence of ABA, the hand remains open, but when ABA is present it nestles in the palm of the PYR1 hand, which closes over the hormone as if holding a ball, thereby enabling a PP2C molecule to sit on top of the folded fingers. As these features seem to be conserved across most members of this protein family, these findings confirm the family as the main ABA receptors. Moreover, they elucidate how the whole process of stress response starts: by binding to PYR1, ABA causes it to hijack PP2C molecules, which are therefore not available to block the stress response.

“If you treat plants with ABA before a drought occurs, they take all their water-saving measures before the drought actually hits, so they are more prepared, and more likely to survive that water shortage – they become more tolerant to drought”, Rodriguez explains. “The problem so far”, Márquez adds, “has been that ABA is very difficult – and expensive – to produce. But thanks to this structural biology approach, we now know what ABA interacts with and how, and this can help to find other molecules with the same effect but which can be feasibly produced and applied.”

To determine the structure of PYR1, the scientists made use of the infrastructure of the Partnership for Structural Biology, including EMBL Grenoble’s high-throughput crystallisation facilities and the beamlines at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, located in the same campus as EMBL Grenoble.