New avenues for eradicating cancer

New single-cell sequencing method has the potential to boost efforts to find cancer-fighting drugs

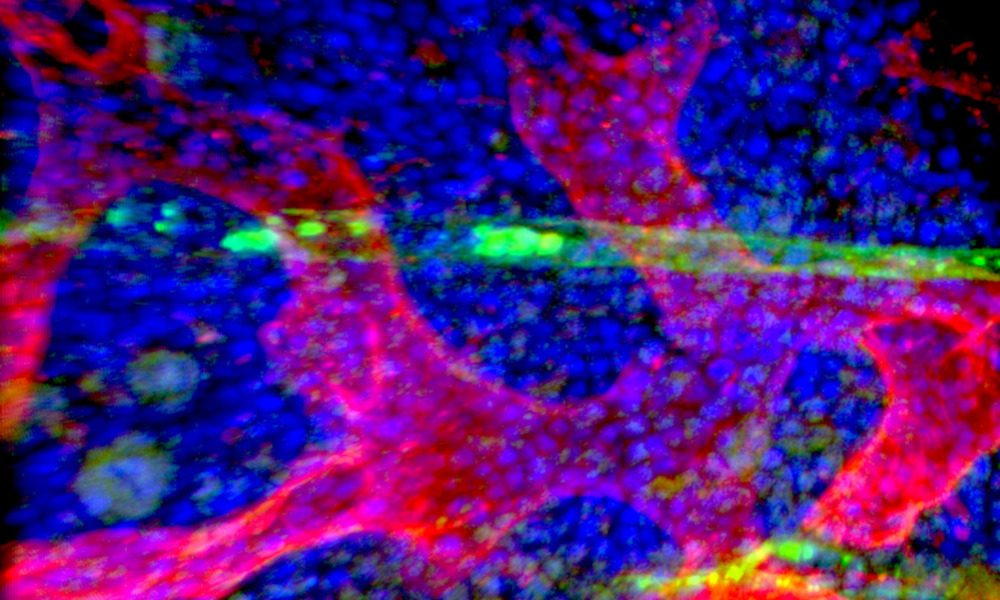

Most cancerous tissue consists of rapidly dividing cells with a limited capacity for self-renewal, meaning that the bulk of cells stop reproducing after a certain number of divisions. However, cancer stem cells can replicate indefinitely, fuelling long-term cancer growth and driving relapse.

Cancer stem cells that elude conventional treatments like chemotherapy are one of the reasons patients initially enter remission but relapse soon after. In acute myeloid leukaemia, a form of blood cancer, the high probability of relapse means that fewer than 15% of elderly patients live longer than five years.

However, cancer stem cells are difficult to isolate and study because of their low abundance and similarity to other types of stem cell. This has hampered international research efforts to develop precision treatments that target malignant cells while sparing healthy ones.

Researchers from EMBL and the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona have overcome this problem by developing a method called MutaSeq, which can be used to distinguish between cancer stem cells, mature cancer cells, and otherwise healthy stem cells based on their genetics and gene expression patterns.

“RNA provides vital information for human health. For example, PCR tests for coronavirus detect its RNA to diagnose COVID-19. Subsequent sequencing can determine the virus variant,” explains Lars Velten, Group Leader at the CRG. “MutaSeq works like a PCR test for coronavirus, but at a much more complex level and with a single cell as starting material.”

To determine if a single cell was a stem cell, the researchers used MutaSeq to measure thousands of RNAs in that cell at the same time. To then find out if the cell was cancerous or healthy, the researchers carried out additional sequencing and looked for mutations. The resulting data helped them track whether stems cells are cancerous or healthy and helped to determine what makes the cancer stem cells different.

“There are a huge number of small-molecule drugs out there with demonstrated clinical safety, but deciding which cancers and more specifically which patients these drugs are well suited for is a daunting task,” says Lars Steinmetz, Group Leader and Senior Scientist at EMBL Heidelberg. “Our method can identify drug targets that might not have been tested in the right context. These tests will need to be carried out in controlled clinical studies, but knowing what to try is an important first step.”

The method is based on single-cell sequencing, an increasingly common technique that helps researchers gather and interpret genome-wide information from thousands of individual cells. Single-cell sequencing provides a highly detailed molecular profile of complex tissues and cancers, opening new avenues for research.

Explaining their next steps, Velten says: “We have now brought together clinical researchers from Germany and Spain to apply this method in much larger clinical studies. We are also making the method much more streamlined. Our vision is to identify cancer stem cell-specific drug targets in a personalised manner, making it ultimately as easy for patients and doctors to look for these treatments as to test for coronavirus.”