Exploring genetic variation

EMBL group leader Jan Korbel reflects on his scientific origins and current research

Growing up, the books Jan Korbel liked to read were standard childhood fodder: astronomy, dinosaurs, and archaeology caught his imagination. It was only in his final years at school, when he started learning about genetics, that an interest in biology really took hold. “I had a very good teacher,” he says. “She later told me that she was always quite sceptical about genetics but apparently it didn’t show! It’s a fascination I had at the age of fifteen that’s never gone away.”

Combining disciplines

As an undergraduate, Korbel spent a few months as an intern at the Roslin Insitute in Edinburgh, UK, at the same time that Dolly the sheep – the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell – was in residence. “I basically took my first step in molecular biology at the Roslin Institute,” he explains. “I was intrigued. Knowing that they’d developed this way of cloning sheep got me excited about molecular biology. The experimental research I pursued there inspired me, and later led me to study computational biology with a molecular biology angle. It was a fascinating and helpful time.”

Both computational and more traditional lab research now happen side by side in Korbel’s lab at EMBL. “That’s getting more common, because nearly all laboratories need some level of computational expertise now,” he explains, “although often you’ll have experimental labs bringing in people from the computational side. For me, it was the other way round: initially, most of my research came from a computational angle, but I was always close to experimental researchers and I was lucky because I got the right people in my lab. It now feels very natural for us to combine the two approaches.”

Shattering chromosomes

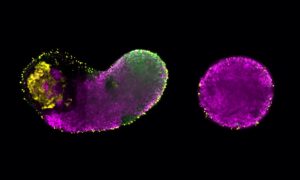

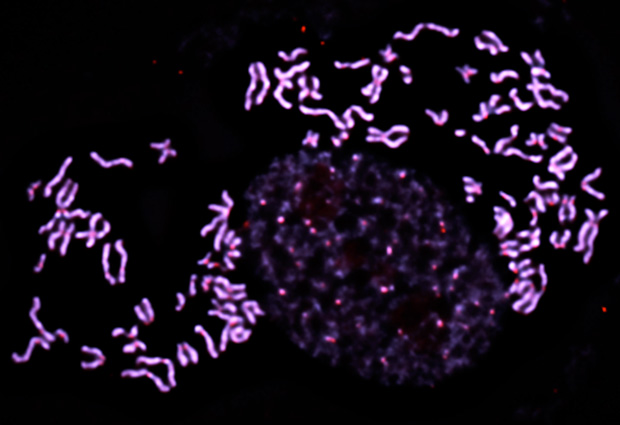

Korbel’s research focuses on structural variation in the human genome: that is, how our DNA rearranges – a process that occurs dynamically and has implications for ageing and diseases, including cancer. One area of study is a process the Korbel group co-discovered, known as chromothripsis, or ‘chromosome shattering’. In this process, a chromosome undergoes multiple structural rearrangements in a single catastrophic event. Korbel and his lab have been working to uncover the molecular processes by which chromothripsis occurs. It had previously been thought that the development of cancer was a process of gradual changes, but the discovery of chromothripsis showed that these gradual processes can also be punctuated by sudden large changes, in which many mutations critical for cancer development can happen all at once.

“Intriguingly, when chromothripsis occurs in cancer it’s nearly always one of the earliest mutations. That implies that there might be certain selective boundaries, where cells need massive changes before they can develop into tumours,” explains Korbel. “We believe chromothripsis is a very strong facilitator of that process.”

Finding a theme

Korbel is now one of the leaders of the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes project, which aims to identify common patterns of mutation among more than 2,600 whole genomes taken from various types of cancer. At the European Association for Cancer Research (EACR) Congress in July, he will receive the Pezcoller Foundation-EACR Cancer Researcher Award, which is presented every two years to a researcher who’s made important contributions to the field of cancer research.

“It’s a huge honour for me, because it recognises the work of my group that started here at EMBL, and acknowledges that within our network of collaborators we were able to develop our own research theme, around how genomes rearrange in cancer,” says Korbel. “It’s a very strong motivation for us to continue pursuing this vital area of research.”