Flexible and protected – new findings on SARS-CoV-2 protein shed light on virus’s ability to infect cells

In the fight against the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 researchers from multiple research institutions in Germany have combined their resources to study the spike protein on the surface of the virus. With its spikes, the virus binds to human cells and infects them. The study gave surprising insights into the spike protein, including an unexpected freedom of movement and a protective coat to hide it from antibodies. The results are published in Science.

At the start of a COVID-19 infection, the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 docks onto human cells using the spike-like proteins on its surface. The spike protein is at the centre of vaccine development because it triggers an immune response in humans. A group of German scientists, including members of EMBL in Heidelberg, the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, and Goethe University Frankfurt have focused on the surface structure of the virus to gain insights they can use for the development of vaccines and of effective therapeutics to treat infected patients.

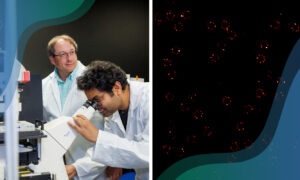

The team combined cryo-electron tomography, subtomogram averaging, and molecular dynamics simulations to analyse the molecular structure of the spike protein in its natural environment, on intact virions, and with near-atomic resolution. Using EMBL’s state-of-the-art cryo-electron microscopy imaging facility, 266 cryotomograms of about 1000 different viruses were generated, each carrying an average of 40 spikes on its surface. Subtomogram averaging and image processing, combined with molecular dynamics simulations, finally provided the important and novel structural information on these spikes.

The results were surprising: the data showed that the globular portion of the spike protein, which contains the receptor-binding region and the machinery required for fusion with the target cell, is connected to a flexible stalk. “The upper spherical part of the spike has a structure that is well reproduced by recombinant proteins used for vaccine development,” explains Martin Beck, EMBL group leader and a director of the Max Planck Institute (MPI) of Biophysics. “However, our findings about the stalk, which fixes the globular part of the spike protein to the virus surface, were new.”

Credit: EMBL

“The stalk was expected to be quite rigid,” adds Gerhard Hummer, from the MPI of Biophysics and the Institute of Biophysics at Goethe University Frankfurt. “But in our computer models and in the actual images, we discovered that the stalks are extremely flexible.” By combining molecular dynamics simulations and cryo-electron tomography, the team identified the three joints – hip, knee and ankle – that give the stalk its flexibility.

“Like a balloon on a string, the spikes appear to move on the surface of the virus and thus are able to search for the receptor for docking to the target cell,” explains Jacomine Krijnse Locker, group leader at the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut. To prevent infection, these spikes are targeted by antibodies. However, the images and models also showed that the entire spike protein, including the stalk, is covered with chains of glycans – sugar-like molecules. These chains provide a kind of protective coat that hides the spikes from neutralising antibodies: another important finding on the way to effective vaccines and medicines.

Flexibel und geschützt – Neue Erkenntnisse über ein SARS-CoV-2-Protein geben Aufschluss über die Fähigkeit des Virus, Zellen zu infizieren

Im Kampf gegen das Coronavirus haben Forscher von SARS-CoV-2 aus mehreren Forschungseinrichtungen in Deutschland ihre Ressourcen gebündelt, um das Spike-Protein auf der Oberfläche des Virus zu untersuchen. Mit diesen Stacheln bindet sich das Virus an menschliche Zellen und infiziert sie. Die Studie ergab überraschende Einblicke in das Spike-Protein, darunter eine unerwartete Bewegungsfreiheit und eine Schutzhülle, die es vor Antikörpern versteckt. Die Ergebnisse wurden in Science veröffentlicht.

Zu Beginn einer COVID-19-Infektion dockt das Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 mit Hilfe von Stachel-ähnlichen Proteinen an seiner Oberfläche an menschliche Zellen an. Dieses Protein steht im Zentrum der Impfstoffentwicklung, weil es beim Menschen eine Immunantwort auslöst. Eine Gruppe deutscher Wissenschaftler, darunter Mitglieder des EMBL in Heidelberg, des Max-Planck-Instituts für Biophysik, des Paul-Ehrlich-Instituts und der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, hat sich mit der Oberflächenstruktur des Virus befasst, um Erkenntnisse zu gewinnen, die für die Entwicklung von Impfstoffen und wirksamen Therapeutika zur Behandlung infizierter Patienten benutzt werden können.

Das Team kombinierte Kryo-Elektronentomographie, Subtomogramm-Mittelung und Molekulardynamik-Simulationen, um die molekulare Struktur des Spike-Proteins in seiner natürlichen Umgebung, an intakten Viren und mit nahezu atomarer Auflösung zu analysieren. Mit Hilfe der hochmodernen Kryo-Elektronenmikroskopie-Bildgebungsanlage des EMBL wurden 266 Kryotomogramme von etwa 1000 verschiedenen Viren erzeugt, von denen jedes durchschnittlich 40 Spike-Proteine auf seiner Oberfläche trägt. Subtomogramm-Mittelung und Bildverarbeitung, kombiniert mit Molekulardynamik-Simulationen, lieferten schließlich die wichtigen und neuartigen strukturellen Informationen zu diesen Stacheln.

Die Ergebnisse waren überraschend: Die Daten zeigten, dass der kugelförmige Teil des Spike-Proteins, der die rezeptorbindende Region und die für die Fusion mit der Zielzelle erforderliche Maschinerie enthält, mit einem flexiblen Stiel verbunden ist. „Der obere kugelförmige Teil des Spike-Proteins hat eine Struktur, die von rekombinanten Proteinen, die für die Impfstoffentwicklung verwendet werden, gut reproduziert wird,” erklärt Martin Beck, Gruppenleiter am EMBL und Direktor des Max-Planck-Instituts (MPI) für Biophysik. „Unsere Erkenntnisse über den Stiel, der den kugelförmigen Teil des Spike-Proteins an der Virusoberfläche fixiert, waren jedoch neu.“

„Es wurde erwartet, dass der Stiel ziemlich starr sein würde,” fügt Gerhard Hummer vom MPI für Biophysik und dem Institut für Biophysik der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt hinzu. „Aber in unseren Computermodellen und in den tatsächlichen Bildern entdeckten wir, dass die Stängel extrem flexibel sind. Durch die Kombination von Molekulardynamiksimulationen und Kryo-Elektronentomographie identifizierte das Team die drei Gelenke – Hüfte, Knie und Knöchel –, die dem Stängel seine Flexibilität verleihen. „Wie ein Ballon an einer Schnur scheinen sich die Stängel auf der Oberfläche des Virus zu bewegen und können so nach dem Rezeptor für das Andocken an die Zielzelle suchen,“ erklärt Jacomine Krijnse Locker, Gruppenleiterin am Paul-Ehrlich-Institut. Um eine Infektion zu verhindern, werden diese Stacheln von Antikörpern angegriffen. Die Bilder und Modelle zeigten aber auch, dass das gesamte Spike-Protein, einschließlich des Stiels, mit Ketten aus Glykanen – zuckerähnlichen Molekülen – bedeckt ist. Diese Ketten bilden eine Art Schutzmantel, der die Stacheln vor neutralisierenden Antikörpern verbirgt: eine weitere wichtige Erkenntnis auf dem Weg zu wirksamen Impfstoffen und Medikamenten.