From fireman to arsonist

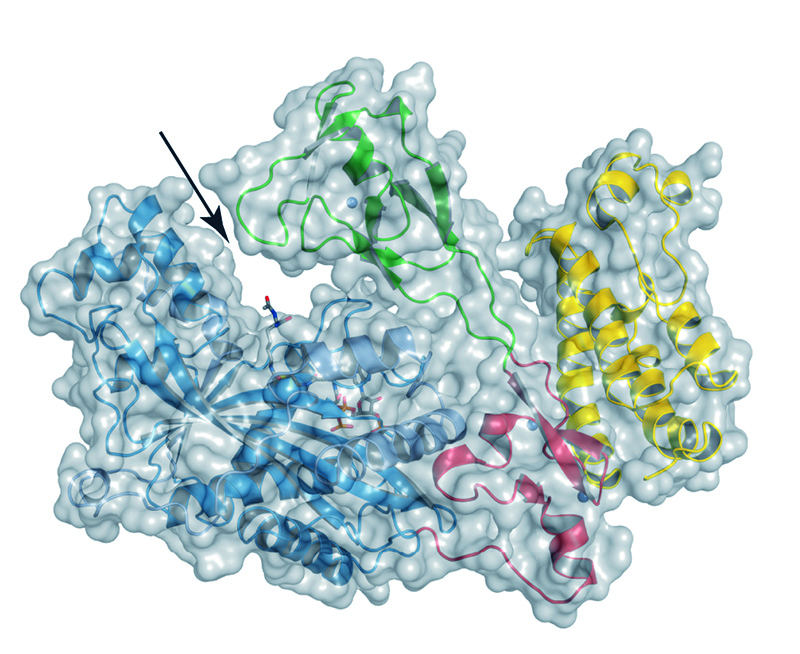

Secret life of a cancer-related protein revealed by 3D structure

In a nutshell:

– Tumour-suppressor protein p300 can turn into an oncogene

– Discovered through first 3D structure of protein’s active core

– Means the protein could be a viable drug target

Like a fireman who becomes an arsonist, a protein that prevents cells becoming cancerous can also cause tumours, scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Grenoble, France, have discovered. The finding, published today in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, stems from the first 3D structure of the protein’s active core, and opens up new avenues for drug design.

“Everybody thought this protein was a tumour-suppressor,” says Daniel Panne, who led the work, “but we’ve found that some mutations make it an oncogene – a gene that turns the cell cancerous – which actually makes it a viable drug target.”

Surprisingly, the finding reveals that mutations to this protein that have been linked to cancer can act in two different ways. As expected, some mutations make this ‘fireman’ protein – known as p300 – unable to put out the fire: they cause it to malfunction and lose control over other genes, thwarting its tumour-suppressor role. But, as Panne and colleagues discovered, some cancer-linked mutations actually make p300 into an arsonist: they make it hyperactive, turning it into an oncogene. Which mutations are which? The secret lies in an unexpected piece of the puzzle.

In this study, Panne and colleagues determined the structure of the whole of the protein’s active core – the part that physically interacts with genetic material to control genes – for the first time. They found that this 3D puzzle had one more piece than expected. p300 has a groove that it uses to slot onto the cell’s genetic material to activate or inactivate genes, and the EMBL scientists found that, sitting on top of that groove like a lid, was a piece no-one knew this protein had. This ‘lid’ is like a built-in self-control mechanism. It determines whether the protein can slot onto genetic material or not: for p300 to do its job, it has to open the lid. But if a mutation interferes with the lid, keeping it permanently open, the protein will go into over-drive, and the resulting uncontrolled gene activity can lead to cancer.

Tumours caused by these hyper-activating mutations could potentially be fought by drugs that inhibit p300. So, armed with the knowledge of the protein’s structure, the EMBL scientists now plan to investigate how to thwart p300 when it goes from fireman to arsonist.