Making the most of what you have

Bacterium fine-tunes proteins for enhanced functionality

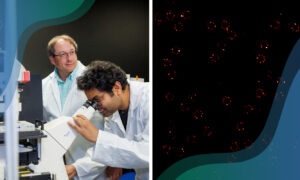

The bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which causes atypical pneumonia, is helping scientists uncover how cells make the most of limited resources. By measuring all the proteins this bacterium produces, scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, and collaborators, have found that the secret is fine-tuning.

Like a mechanic can fine-tune a car after it has left the factory, cells have ways to tweak proteins, changing their chemical properties after production – so-called post-translational modifications. Anne-Claude Gavin, Peer Bork and colleagues at EMBL measured how many of M. pneumoniae’s proteins had certain modifications. They found that two forms of tweaking which were known to be common in our own cells are equally prevalent in this simple bacterium. Called phosphorylation and lysine acetylation, these two types of post-translational modification also talk to and interfere with each other: the scientists found that disrupting one can cause changes in the other. Since M. pneumoniae is one of the living organisms with the fewest different proteins, this interplay between phosphorylation and lysine acetylation may be a way of getting additional functions out of a limited number of proteins: by tweaking each protein in several ways, enabling it to perform a variety of tasks. And, as more complex cells like our own share the same protein-tweaking tactics, it is probably an ancient strategy that evolved before our branch of the evolutionary tree and M.pneumoniae’s branched their separate ways.

The scientists also found that phosphorylation levels in M. pneumoniae control how much of each protein the bacterium has. Interestingly, it does so not only by influencing whether protein-building instructions encoded in DNA are read, but also by altering proteins that are involved in building other proteins. This fine-tuning may enable the cell to react faster to changing needs or situations.

When they disrupted M. pneumoniae’s ability to tweak proteins, Gavin, Bork and colleagues also discovered that disaster doesn’t necessarily ensue. As in our own cells, proteins in this bacterium rarely work alone. They interact with each other, work together, or perform different steps in chain reactions. The scientists found that these protein networks have a certain buffering ability: disrupting one protein can affect its immediate partners, but the problems may not propagate throughout the whole network. The scientists hope that mapping the different networks may one day enable them to predict where a targeted disruption might do the most damage, which could eventually provide valuable information for drug design.

The work, published online today in Molecular Systems Biology, was conducted in collaboration with the Centro de Regulacion Genomica in Barcelona, Spain, Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and Georg-August University Göttingen and Heidelberg University, both in Germany.

Read this release in Spanish and in Catalan on the CRG website (select language in top right-hand corner).

Read about the group’s previous work on Mycoplasma:

What a minimal self-sufficient cell can’t do without