Parental chromosomes kept apart during first division

EMBL scientists show that mammalian life begins differently than we thought

It was long thought that during an embryo’s first cell division, one spindle is responsible for segregating the embryo’s chromosomes into two cells. EMBL scientists now show that in mice, there are actually two spindles, one for each set of parental chromosomes, meaning that the genetic information from each parent is kept apart throughout the first division. Science publishes the results – bound to change biology textbooks – on 12 July 2018.

This dual spindle formation might explain part of the high error rate in the early developmental stages of mammals, spanning the first few cell divisions. “The aim of this project was to find out why so many mistakes happen in those first divisions,” says Jan Ellenberg, the group leader at EMBL who led the project. “We already knew about dual spindle formation in simpler organisms like insects, but we never thought this would be the case in mammals like mice. This finding was a big surprise, showing that you should always be prepared for the unexpected.”

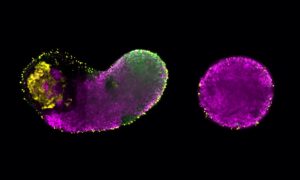

Video revealing how the two parental genomes (labelled in pink and blue) remain spatially separate throughout the first cell division (text continues below).

Solving a 20-year-old mystery

Scientists have always seen parental chromosomes occupying two half-moon-shaped parts in the nucleus of two-cell embryos, but it wasn’t clear how this could be explained. “First, we were looking at the motion of parental chromosomes only, and we couldn’t make sense of the cause of the separation,” says Judith Reichmann, scientist in EMBL’s Ellenberg group and first author of the paper. “Only when focusing on the microtubules – the dynamic structures that spindles are made of – could we see the dual spindles for the first time. This allowed us to provide an explanation for this 20-year-old mystery.”

What is mitosis?

Mitosis is the process of cell division, when one cell splits into two daughter cells. It occurs throughout the lifespan of multi-cellular organisms but is particularly important when the organism grows and develops. The key step of mitosis is to pass an identical copy of the genome to the next cell generation. For this to happen, DNA is duplicated and organised into dense thread-like structures known as chromosomes. The chromosomes are then attached to long protein fibres – organised into a spindle – which pulls the chromosomes apart and triggers the formation of two new cells.

What is the spindle?

The spindle is made of thin, tube-like protein assemblies known as microtubules. During mitosis of animal cells, groups of such tubes grow dynamically and self-organise into a bi-polar spindle that surrounds the chromosomes. The microtubule fibres grow towards the chromosomes and connect with them, in preparation for chromosome separation to the daughter cells. Normally there is only one bi-polar spindle per cell, however, this research suggests that during the first cell division there are two: one each for the maternal and paternal chromosomes.

New molecular targets

“The dual spindles provide a previously unknown mechanism – and thus a possible explanation – for one of the common mistakes we see in the first divisions of mammalian embryos,” Ellenberg explains. Such mistakes can result in cells with multiple nuclei, terminating development. “Now, we have a new mechanism to go after and identify new molecular targets. It will be important to find out if it works the same in humans, because that could provide valuable information for research on how to improve human infertility treatment, for example.”

The beginning of life

Furthermore, the knowledge from this paper might impact legislation. In some countries, the law states that human life begins – and is thus protected – when the maternal and paternal nuclei fuse after fertilisation. If it turns out that the dual spindle process works the same in humans, this definition is not fully accurate, as the union in one nucleus happens slightly later, after the first cell division.

Impossible until now

This discovery would have been impossible without the light-sheet microscopy technology developed in Ellenberg’s and Lars Hufnagel’s group at EMBL, which is now available through the EMBL spin-off company Luxendo. This allows for real-time and 3D imaging of the early stages of development, when embryos are very sensitive to light and would be damaged by conventional light microscopy methods. The high speed and spatial precision of light-sheet microscopy drastically reduce the amount of light that the embryo is exposed to, making a detailed analysis of these formerly hidden processes possible.

This work was supported by the ERC Advanced Grant “Corema” (grant agreement 694236) and by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory. The authors were further supported by the EMBL Interdisciplinary Postdoc Programme (EIPOD) under Marie Curie Actions COFUND; by the EMBO long-term postdoctoral fellowship and EC Marie Sklodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellowship; by a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds Phd fellowship, and by a Humboldt Foundation postdoctoral fellowship.

Die Chromosomen der Eltern bleiben während der ersten Teilung des Embryos getrennt

Wissenschaftler des EMBL zeigen, dass das Leben von Säugetieren anders beginnt als gedacht

Lange dachte man, dass bei der ersten embryonalen Zellteilung nur eine Spindel für die Auftrennung aller Chromosomen des Embryos in zwei Zellen verantwortlich ist. EMBL-Wissenschaftler zeigen nun, dass es tatsächlich aber zwei Spindeln gibt, eine für jeden elterlichen Chromosomensatz; das bedeutet, dass die genetischen Informationen von Mutter und Vater während der ersten Teilung getrennt gehalten werden. Science veröffentlicht die Ergebnisse – die ein Umschreiben der Biologielehrbücher zur Folge haben dürften – am 12. Juli 2018.

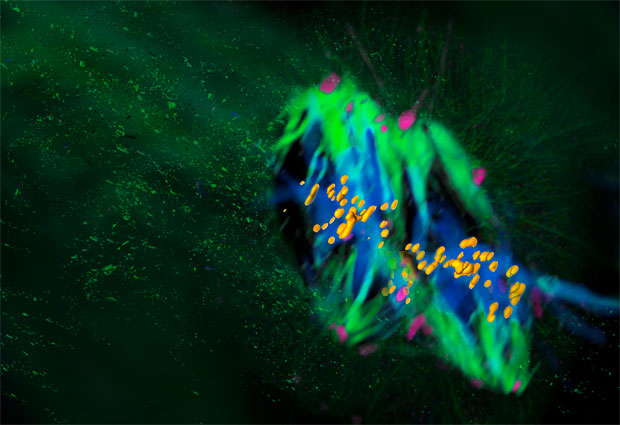

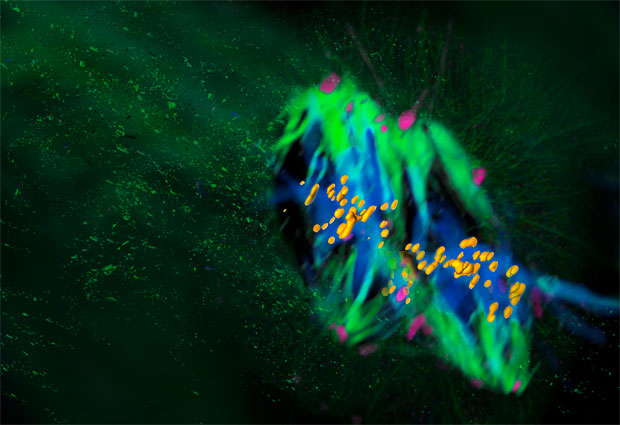

In Grün sind die Mikroturboli dargestellt aus denen die Spindel besteht und Pink stellt das Zentrosom dar: Das Hauptzentrum, das die Mikroturboli organisiert. Die DNA ist in Blau dargestellt, und Orange zeigt die Kinetochoren: Proteinstrukturen, an denen sich die Mikroturboli während der Zellteilung befestigen, um die Chromosomen auseinander zu ziehen.

Die Bildung dieser Doppelspindel könnte einen Teil der hohen Fehlerrate in den frühen Entwicklungsstadien während der ersten Zellteilungen von Säugetieren erklären. „Ziel dieses Projekts war es, herauszufinden, warum bei den ersten Teilungen so viele Fehler passieren“, sagt Jan Ellenberg, der Gruppenleiter am EMBL, der das Projekt leitete. „Wir wussten bereits, dass bei einfacheren Tieren wie Insekten zwei Spindeln gebildet werden, hätten aber niemals vermutet, dass dies auch bei Säugetieren wie Mäusen der Fall ist. Dieses Ergebnis war eine große Überraschung für uns und zeigt, dass man immer auf das Unerwartete vorbereitet sein sollte.“

Auflösung eines 20 Jahre alten Rätsels

Wissenschaftler hatten schon lange beobachtet, dass die elterlichen Chromosomen sich in den runden Zellkernen zweizelliger Embryonen wie zwei Halbmonde anordnen, doch niemand wusste eine Erklärung dafür. „Anfangs haben wir die Bewegungen der elterlichen Chromosomen verfolgt, wir konnten aber keine Ursache für diese Verteilung finden“, erklärt Judith Reichmann, Wissenschaftlerin in der Ellenberg-Gruppe am EMBL und Erstautorin des Artikels. „Erst, als wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit auf die Mikrotubuli – die dynamischen Strukturen, aus denen die Spindeln bestehen – richteten, konnten wir zum ersten Mal die Doppelspindeln sehen. Damit konnten wir eine Erklärung für dieses 20 Jahre alte Rätsel liefern.“

Neue molekulare Zielstrukturen

„Die Doppelspindeln liefern einen bisher unbekannten Mechanismus – und damit eine mögliche Erklärung – für einen der Fehler, die wir bei den ersten Teilungen von Säugetierembryonen beobachten“, erklärt Ellenberg. Solche Fehler können zu mehrkernigen Zellen und dadurch zum Abbruch der Entwicklung des Embryos führen. „Jetzt haben wir einen bisher unbekannten Mechanismus, den wir untersuchen können, um neue molekulare Zielstrukturen zu identifizieren. Es wird in Zukunft auch wichtig sein herauszufinden, ob dieser Prozess beim Menschen genauso abläuft. Dadurch könnte man zum Beispiel wertvolle Informationen für die zukünftige Forschung zur Verbesserung der Behandlung der Unfruchtbarkeit beim Menschen erhalten.“

Der Beginn des Lebens

Darüber hinaus könnten die Erkenntnisse dieser Arbeit Auswirkungen auf Gesetzestexte haben. Nach der Rechtsauffassung in einigen Ländern beginnt das menschliche Leben – und damit sein Schutz – mit der Verschmelzung des mütterlichen und des väterlichen Zellkerns nach der Befruchtung. Sollte die Doppelspindelbildung beim Menschen ähnlich ablaufen wie in Mäusen, wäre diese Definition nicht mehr ganz richtig. Die Bildung eines gemeinsamen Zellkerns fände dann erst nach der ersten Zellteilung statt.

Erst jetzt möglich

Diese Entdeckung wäre ohne die Lichtblattmikroskopie nicht möglich gewesen. Diese Technologie wurde in der Gruppe um Jan Ellenberg und Lars Hufnagel am EMBL weiterentwickelt und ist inzwischen über das EMBL-Spin-off-Unternehmen Luxendo erhältlich. Mithilfe dieses Verfahrens lassen sich die frühen Entwicklungsstadien, in denen Embryonen sehr lichtempfindlich sind und durch herkömmliche lichtmikroskopische Methoden geschädigt würden, in Echtzeit und 3D beobachten. Die sehr kurze und räumliche präzise Beleuchtung in der Lichtblattmikroskopie verringert drastisch die Lichtenergie, mit der der Embryo untersucht wird, und ermöglichte damit eine detaillierte Untersuchung dieser bislang verborgenen Vorgänge.