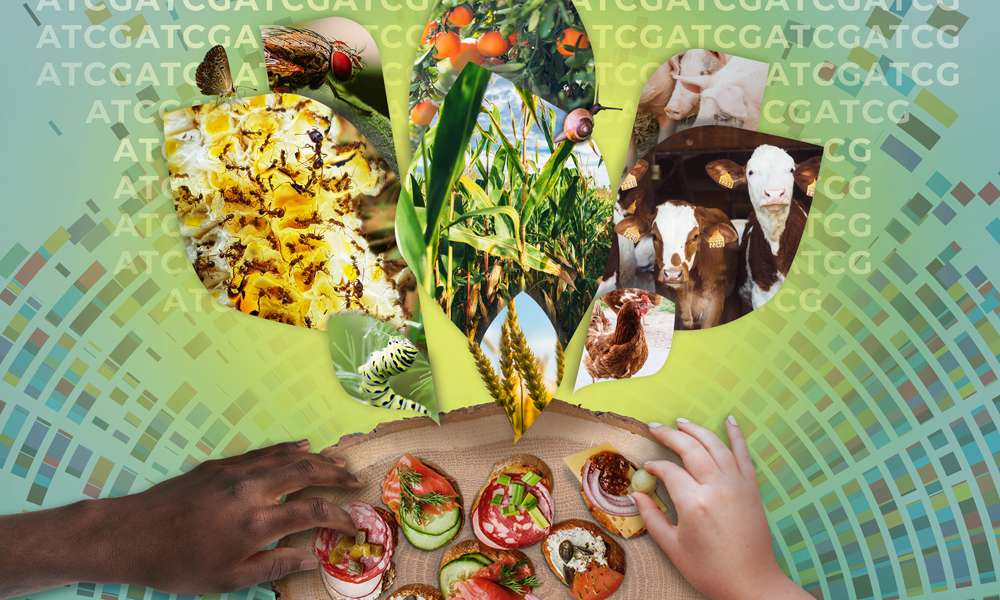

Can data help feed a hungry world?

Feeding a growing population in a changing world requires new technologies, collaboration, and a whole lot of data. The need is clear and urgent: in 2020, 2.37 billion people did not have access to enough safe, nutritious food.

Scientists around the world are working to solve this problem in a number of ways, for example improving crop yields or producing disease-resistant, drought-protected crops. Much of the data and insights they generate find their way into EMBL-EBI data resources – openly and freely available libraries of molecular data for all plant and animal species. And these are the data that sit at the heart of finding solutions for feeding the world.

Genomics – an essential tool

“New technologies are enabling researchers to measure traits, or phenotypes, of plant and animal species that global food supplies rely on, and connect them to underlying genomic regions,” explained Sarah Dyer, Ensembl Plants Team Leader at EMBL-EBI.

“Linking genes to desirable traits – such as high yields for a plant, or disease resistance for farmed animals – could be a gamechanger for agriculture. However, such traits are often polygenic in nature, meaning they can’t be traced back to a single gene, which makes the work of linking genotype to phenotype very complex.”

Linking gene to trait

EMBL-EBI is involved in a series of international collaborations working to improve the fundamental understanding of genome to phenome research, with the aim of helping farmers and breeders to make food production more robust and sustainable. These include FAANG, a coordinated initiative to understand genome-to-phenome links in farmed animals, as well as more specialised projects such as BoVReg, which focuses on cattle; GENE SWitCH, working on pigs and chickens; AQUA-FAANG focused on farmed fish and Designing Future Wheat (DFW) for wheat.

“Linking genes to desirable traits […] could be a gamechanger for agriculture.” – Sarah Dyer, Ensembl Plants Team Leader

“Plant and animal genomics can help us produce more healthy food using fewer natural resources, while also improving animal welfare and conserving biodiversity,” said Peter Harrison, Genome Analysis Team Leader at EMBL-EBI.

Adapt to changing climates

“As a warming climate and extreme weather become the norm, we need to futureproof food production. This means using our understanding of genomics to speed up the selection for desirable traits. For example, dairy cattle often produce less milk due to heat-induced stress, when temperatures get too hot. Using genome-wide DNA markers that predict tolerance to heat stress, cows can be bred to be more resilient to the increasingly hot temperatures of our climate,” said Harrison.

“We need robust data infrastructure, analysis tools, and standardisation.” – Peter Harrison, Genome Analysis Team Leader, EMBL-EBI

“But understanding the genotype of desirable traits is no easy feat,” continued Harrison. “It takes experts in bioinformatics, molecular genetics, animal breeding, reproduction physiology, and animal welfare to understand this complex puzzle. We also need robust data infrastructure, analysis tools, and standardisation. This way, data produced in different parts of the world is of a comparable standard. For example, data from Europe can be combined with data from Australia or the Americas, and can be analysed to reveal new insights. This is why coordinated international efforts for standardisation of genomic data, such as FAANG, are so important.”

Equip against disease

“Plant genomes are often very large and sometimes polyploid, meaning they have multiple copies of identical or similar chromosome sets, so they can be difficult to work with,” explained Dyer. “But new genome sequencing technologies are helping us overcome these issues and we’re now seeing high quality genomes for different varieties of the same plant species.”

For example, Ensembl Plants now offers 14 wheat genomes from the 10+ Wheat Genomes and DFW projects, which makes it easy to identify variations specific to each variety. And these datasets are important because they can help producers increase the diversity of their crop.

We know that monocropping is a high-risk strategy – you can lose your entire crop if they’re affected by a disease or pest – whereas diversity can make a crop stronger. Genomics reveals that diversity.

Understand pests and pollinators

“We mustn’t forget about the unseen heroes and villains of plant production: the pollinators and the pests,” continued Dyer. “Taking a genomic approach can inform the design of strategies to deal with pests while protecting pollinators. Ensembl Metazoa is a great place to explore these genomes.”

To make your plants more resilient to pests, researchers need to understand the genomics of the plant and pest alike. One recent example was a project that sequenced the genomes of a set of whiteflies, tiny insects, no larger than 1mm in length, that regularly cause billions of dollars’ worth of damage to cassava, cotton, tomatoes, or bean crops in the developing world. As a result, the genomes of six species of African Cassava whitefly are now available in Ensembl Metazoa for scientists and breeders to better understand these insect pests.

“A genomic approach can inform strategies to deal with pests while protecting pollinators.” – Sarah Dyer, Ensembl Plants Team Leader, EMBL-EBI

These examples are only the beginning of what genomics can do for agriculture. Just as genomics helps us understand human health, it is also a lens for understanding the plants, animals, and insects that global food production depends on. But new discoveries will depend on pooling knowledge from many sources, which is why public data resources like Ensembl are critical.