Muscular hydraulics drives larva-polyp morphogenesis.

Current Biology 16 September 2022

10.1016/j.cub.2022.08.065

Researchers from EMBL’s Ikmi group employed an interdisciplinary approach to show how sea anemone ‘exercise’ changes their developing size and shape, uncovering an intimate relationship between behaviour and body development.

As humans, we know that an active lifestyle gives us some control over our form. When we hit the pavement, track our steps, and head to the gym, we can develop muscle and reduce body fat. Our physical activity helps shape our physical figure. But what if we performed similar aerobics in our earliest forms?

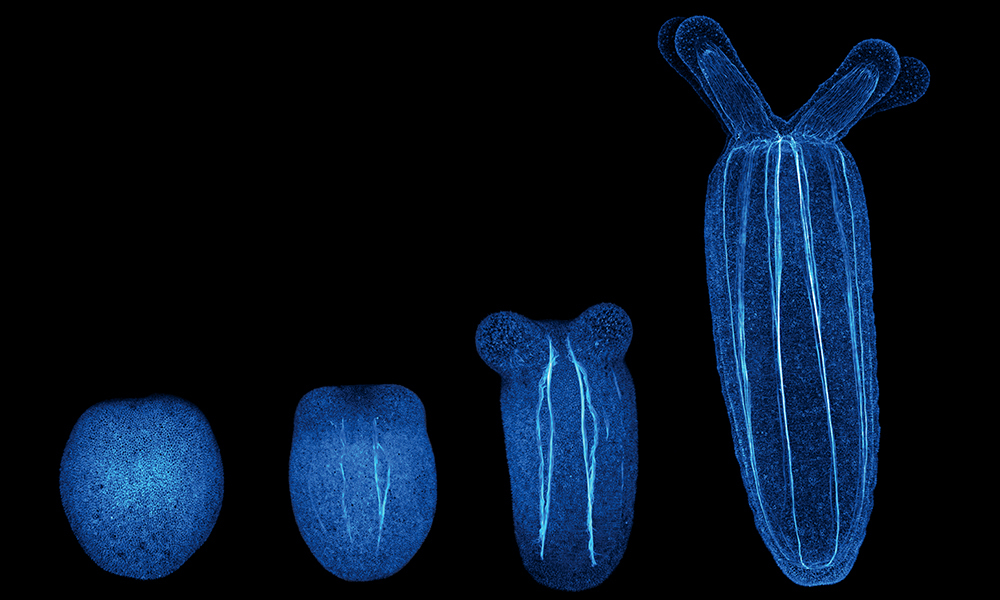

Researchers at EMBL’s Ikmi group turned this question towards the sea anemone to understand how behaviour impacts body shape during early development. Sea anemones, it turns out, also benefit from maintaining an active lifestyle, particularly as they grow from egg-shaped swimming larvae to sedentary, tubular polyps. This morphological transformation is a fundamental transition in the life history of many cnidarian species, including the immortal jellyfish and corals, the builders of our planet’s richest and most complex ecosystems.

During development, starlet sea anemone larvae (Nematostella) perform a specific pattern of gymnastic movements. Too much or too little muscle activity or a drastic change in the organisation of their muscles can cause the sea anemone to deviate from its normal shape.

In a new paper published in Current Biology, the Ikmi group explores how this kind of behaviour impacts animal development. Combining expertise in live imaging, computational methodology, biophysics, and genetics, the multidisciplinary team of scientists collected quantitative data from2D and 3D live imaging to track changes in the body. They found that developing sea anemones behave like hydraulic pumps, regulating body pressure through muscle activity and using hydraulics to sculpt the larval tissue. In many engineered systems, hydraulics is defined by the ability to harness pressure and flow into mechanical work, with long-range effects in space-time.

“Humans use a skeleton made of muscles and bones to exercise. In contrast, sea anemones use a hydroskeleton made of muscles and a cavity filled with water,” said Aissam Ikmi, EMBL Group Leader. The same hydraulic muscles that help the developing sea anemones move also seem to impact how they develop. Using an image analysis pipeline to measure body column length, diameter, estimated volume, and motility in large data sets, scientists found that Nematostella larvae naturally divide themselves into two groups: slow- and fast-developing larvae.

To the team’s surprise, the more active the larvae, the longer they take to develop. “Our work shows how developing sea anemones essentially ‘exercise’ to build their morphology, but it seems that they cannot use their hydroskeleton to move and develop simultaneously,” Ikmi said.

“There were many challenges to doing this research,” explained first author and former EMBL predoc Anniek Stokkermans, now a postdoc at the Hubrecht Institute in the Netherlands. “Nematostella larvae are very active. Most microscopes cannot record fast enough to keep up with its movements, resulting in blurry images, especially when you want to look at it in 3D. Additionally, the animal is quite dense, so most microscopes cannot even see halfway through it.”

To look both deeper and faster, Ling Wang, an application engineer in the Prevedel group at EMBL, built a microscope to capture living, developing sea anemone larvae in 3D.

“For this project, Ling has specifically adapted one of our core technologies, Optical Coherence Microscopy or OCM. The key advantage of OCM is that it allows the animals to move freely under the microscope while still providing a clear, detailed, and 3D look inside.” said Robert Prevedel, EMBL group leader. “It has been an exciting project that shows the many different interfaces between EMBL groups and disciplines.”

With this specialised tool, the researchers were able to quantify volumetric changes in Nematostella tissue and body cavity. “To increase their size, sea anemones inflate like a balloon by taking up water from the environment,” Stokkermans explained. “Then, by contracting different types of muscles, they can regulate their short-term shape, much like squeezing an inflated balloon on one side, and watching it expand on the other side. We think this pressure-driven local expansion helps to stretch the body wall tissue, so the animal slowly becomes more elongated. In this way, contractions can have both short-term and long-term effects.”

To better understand the hydraulics involved in sea anemone movement, the researchers collaborated with experts across disciplines. Prachiti Moghe, an EMBL predoc in the Hiiragi group, measured pressure changes driving body deformations. Additionally, mathematician L. Mahadevan and engineer Aditi Chakrabarti from Harvard University introduced a mathematical model to quantify the role of hydraulic pressures in driving system-level changes in shape. They also engineered reinforced balloons with bands and tapes that mimic the range of shapes and sizes seen in both normal and muscle-defective animals.

“Given the ubiquity of hydrostatic skeletons in the animal kingdom, especially in marine invertebrates, our study suggests that active muscular hydraulics plays a broad role in the design principle of soft-bodied animals,” Ikmi said. “As animal multicellularity evolved in an aquatic environment, we propose that early animals likely exploited the same physics, with hydraulics driving both developmental and behavioural decisions.”

As the Ikmi group previously studied the connections between diet and tentacle development, this research adds a new layer to understanding the evolution of body forms. These findings conceptualize behaviour as a key developmental parameter when studying organisms in their natural habitats. The technologies developed in this project, such as fast, label-free live imaging, are central to grasping how organisms thrive in changing ecosystems, an important aspect of the planetary biology research theme within EMBL’s new Molecules to Ecosystems programme. “We still have many questions from these new findings. Why are there different activity levels? How do cells exactly sense and translate pressure into a developmental outcome?” Stokkermans said, pondering where this research leads. “Furthermore, since tube-like structures form the basis of many of our organs, studying the mechanisms that apply to Nematostella will also help us gain further understanding of how hydraulics plays a role in organ development and function.”

Current Biology 16 September 2022

10.1016/j.cub.2022.08.065