Born With Bristles: New Insights on the Kölliker’s Organs of Octopus Skin

Frontiers in Marine Science 10 May 2021

10.3389/fmars.2021.645738

Some of the most amazing creatures live in the deep blue sea. Cuttlefish, squids and octopuses, for example. These soft-bodied cephalopods have a strikingly sophisticated nervous system, camera-like eyes, three hearts, and an extraordinary ability to switch the colour and texture of their skin to mimic their background in the blink of an eye.

The Mesoscopic Imaging Facility (MIF) at EMBL Barcelona was recently involved in studying one unique feature of the octopus: the ephemeral structures on the surface of their skin called Kölliker’s organs. These structures are present in embryos but disappear before the adult stage, and their function is unknown. MIF examined specimens of hatchlings and juveniles of Octopus vulgaris, or common octopus, as part of a project led by Roger Villanueva from the Institut de Ciències del Mar at CSIC in Spain.

Villanueva and his colleagues examined the Kölliker’s organs – which he described as “mini brooms on the surface of the baby octopuses” – from 17 octopod species collected from around the world. With the help of MIF’s detailed images, the researchers were able to characterise these organs in more detail. They observed that the structures are evenly distributed on the surface of the skin and are roughly the same size, regardless of the size of the species. Their results were recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

“When you calculate the total surface of the octopus when the Kölliker’s organs are spread open towards the outside, the animal increases its total surface by two-thirds,” said Villanueva, “which leads us to think that the organs could be used by the young octopuses to increase their surface-to-volume ratio.” This could help to facilitate the action of flow-related forces such as drag and propulsion. He added: “The distribution of these organs on the surface of the arms, head and mantle of the octopus and their ability to refract light in two directions suggest that they might also have a role in camouflage.”

Montserrat Coll, Mesoscopic Imaging Specialist at EMBL Barcelona and one of the authors of the paper, explained the benefits of using light-sheet microscopy in this study: “Light-sheet microscopy helped to obtain a global picture of the distribution of the Kölliker’s organs on the epithelium. Thanks to our system, we could observe the whole sample without destroying it via histologic cuts. This approach allows us to preserve the specimens for future observation.”

For a detailed image of a Kölliker’s organ, take a look at this image.

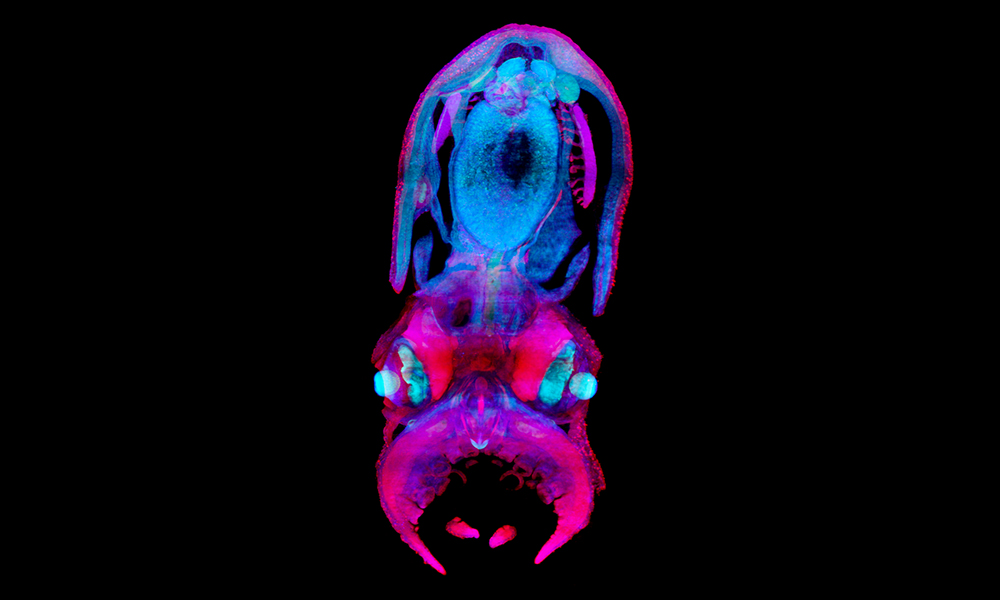

A few images obtained by the MIF staff of octopuses:

Gills in 30-day- (left, center) and 50-day-old (right) Octopus vulgaris.

Here we can see gills, the respiratory organs used by aquatic organisms to extract oxygen from water and expel carbon dioxide. Gills are located inside the mantle cavity of the octopus. Two of the three hearts in an octopus pump blood across the gills. The filamented shape of the gills maximises the active surface across which oxygen interchange can take place. The larger the surface, the higher the oxygen intake per breath. Credit: Montserrat Coll Lladó, Jim Swoger/EMBL; specimens courtesy of Roger Villanueva/ICM-CSIC

Frontiers in Marine Science 10 May 2021

10.3389/fmars.2021.645738