Periodic formation of epithelial somites from human pluripotent stem cells.

Nature communications 28th April 2022

10.1038/s41467-022-29967-1

EMBL Barcelona scientists have recapitulated for the first time in the laboratory how the cellular structures that give rise to our spinal column form sequentially

The spinal column is the central supporting structure of the skeleton in all vertebrates. Not only does it provide a place for muscles to attach, it also protects the spinal cord and nerve roots. Defects in its development are known to cause rare hereditary diseases. Researchers from the Ebisuya Group at EMBL Barcelona have now created a 3D in vitro model that mimics how the precursor structures that give rise to the spinal column form during human embryonic development.

The spinal column consists of 33 vertebrae, which form pairs of precursor structures called somites. Somites give rise to not only our vertebrae, but also our ribs and skeletal muscles. To ensure that these structures are formed correctly, somite development is tightly regulated, and each pair of somites arises at a particular sequential time point in development. This process is controlled by the segmentation clock, which is a group of genes that creates oscillatory waves, every wave giving rise to a new pair of somites.

“For the first time, we have been able to create periodic pairs of human mature somites linked to the segmentation clock in the lab,” said Marina Sanaki-Matsumiya, first author of the study published in Nature Communications. Using this approach, the researchers developed a 3D in vitro model of human somite formation, also known as ‘somitogenesis’.

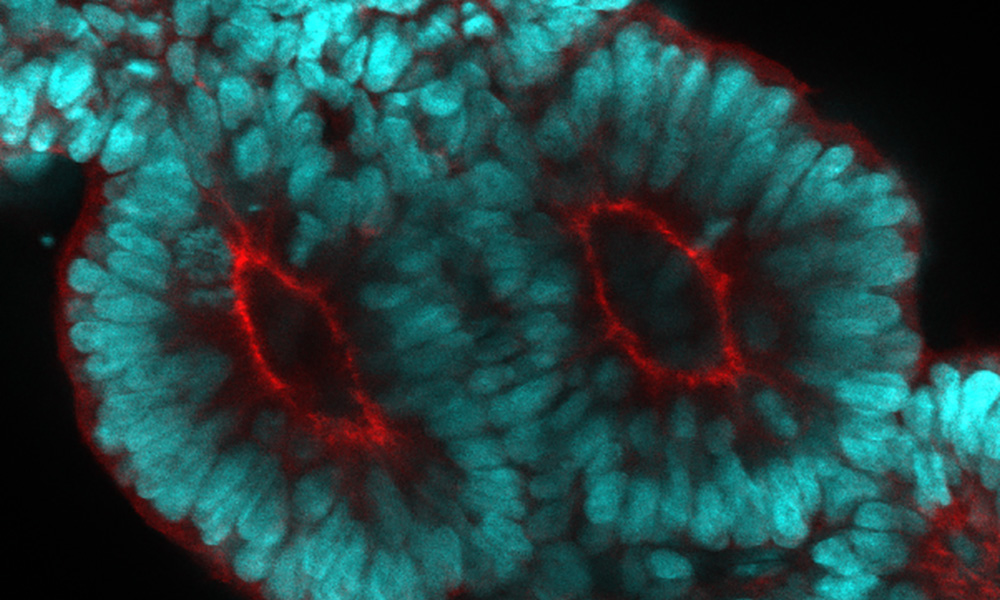

The team cultured human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) in the presence of a cocktail of signalling molecules that induce cell differentiation. Three days later, the cells started to elongate and create anterior (top) and posterior (bottom) axes. At that point, the scientists added Matrigel to the culture mix. Matrigel is what some scientists call the magic powder: a protein mixture that is critical to many developmental processes. This process eventually led to the formation of somitoids – in vitro equivalents of human somite precursor structures.

To test whether the segmentation clock regulates somitogenesis in these somitoids, the researchers monitored the expression patterns of HES7, the core gene involved in the process. They found clear evidence of oscillations, especially when somitogenesis was about to start. The somites that formed also had clear markers of epithelization – an important step in their maturation.

The Ebisuya group studies how and why we humans are different from other species when it comes to embryonic development. One of the model systems they use to understand interspecies differences is the segmentation clock. In 2020, the group uncovered that the oscillation period of the human segmentation clock is longer than the mouse segmentation clock.

The current study also shows a link between the size of somites and the segmentation clock. “The somites that were generated had a constant size, independently of the number of cells used for the initial somitoid. The somite size did not increase even if the initial cell number did.” explained Sanaki-Matsumiya. “This suggests that the somites have a preferred species-specific size, which might be determined by local cell-cell interactions, the segmentation clock, or other mechanisms.”

To study this further, Miki Ebisuya and her group are now planning to grow somitoids of different species and compare them. The researchers are already working on several mammalian species, including rabbits, cattle, and rhinoceroses, setting up a ‘stem cell zoo’ in the lab.

“Our next project will focus on creating somitoids from different species, measure their cell proliferation and cell migration speed to establish what and how somitogenesis is different among species,” said Ebisuya.

La columna vertebral es la estructura central de soporte del esqueleto. No sólo proporciona fijación para los músculos, sino que también protege la médula espinal y las raíces nerviosas. Se sabe que los defectos en su desarrollo causan enfermedades hereditarias raras.

Investigadores del grupo de la Dra. Miki Ebisuya del EMBL Barcelona crean un modelo 3D in vitro que imita cómo se forman las estructuras precursoras que dan lugar a la columna vertebral durante el desarrollo embrionario humano.

La columna vertebral consta de 33 vértebras, que se forman a partir pares de estructuras precursoras llamadas somitas. Los somitas no sólo dan lugar a las vértebras, sino también a las costillas y a los músculos del esqueleto. Para garantizar la correcta formación de estas estructuras, el desarrollo de los somitas está estrechamente regulado y cada par de somitas surge en un momento determinado del desarrollo. Este proceso está controlado por el reloj de segmentación, que es un grupo de genes que crea ondas oscilantes, cada una de las cuales da lugar a un nuevo par de somitas.

“Por primera vez, hemos podido crear en el laboratorio pares periódicos de somitas maduros humanos vinculadas al reloj de segmentación”, afirma Marina Sanaki-Matsumiya, primera autora del estudio publicado en Nature Communications. Con este método, los investigadores desarrollaron un modelo 3D in vitro de formación de somitas humanos, también conocido como “somitogénesis”.

El equipo cultivó células madre humanas pluripotentes inducidas (hiPSC por sus siglas en inglés) con un cóctel de moléculas de señalización que inducen la diferenciación celular.

Tres días después, los grupos de células comenzaron a alargarse y a crear ejes anteriores (arriba) y posteriores (abajo). En ese momento, los científicos añadieron Matrigel a la mezcla de cultivo. Matrigel es lo que algunos científicos llaman el polvo mágico: una mezcla de proteínas que es crucial para varios procesos del desarrollo. Este proceso condujo finalmente a la formación de somitoides, que serían los equivalentes in vitro de las estructuras precursoras de los somitas humanos.

Para comprobar si el reloj de segmentación regula la somitogénesis en estos somitoides, los investigadores controlaron los patrones de expresión de HES7, el gen central implicado en el proceso. Encontraron claras evidencias de oscilaciones, especialmente cuando la somitogénesis estaba a punto de comenzar. Los somitas que se formaron también tenían claros marcadores de epitelización, un paso importante en su maduración.

El grupo de investigación liderado por la Dra. Miki Ebisuya estudia cómo y por qué los humanos somos diferentes de otras especies en lo que respecta al desarrollo embrionario. Uno de los sistemas modelo de diferencias entre especies que utilizan es el reloj de segmentación. En 2020, el grupo descubrió que el periodo de oscilación del reloj de segmentación humano es más largo que el del ratón.

El estudio actual también muestra una relación entre el tamaño de los somitas y el reloj de segmentación. “Los somitoides que creamos, independientemente del número de células iniciales, tenían un tamaño de somita que era constante. No aumentaba aunque lo hiciera el número de células iniciales”, explica Sanaki-Matsumiya. “Esto sugiere que los somitas tienen un tamaño preferido, que podría estar determinado por las interacciones locales célula-célula, el reloj de segmentación u otros mecanismos”.

Para profundizar en el estudio, Ebisuya y su grupo planean ahora cultivar somitoides de diferentes especies y compararlos. Los investigadores ya están trabajando con varias especies de mamíferos, como conejos, bovinos y rinocerontes, creando un “zoo de células madre” en el laboratorio.

“Nuestro próximo proyecto se centrará en crear somitoides de diferentes especies, medir su proliferación celular y la velocidad de migración de las células para establecer qué y cómo la somitogénesis es diferente entre las especies”, dice Ebisuya.

Nature communications 28th April 2022

10.1038/s41467-022-29967-1